How widespread was the Justinian Plague in the 6th century? And how devastating? New research indicates a situation much like that of the Later Middle Ages

Yersinia Pestis is the bacteria responsible for the pandemics in the early as well as later Middle Ages. Present in diverse forms, the bubonic was perhaps less virulent than the pneumonic. Nevertheless, the events in the 14th and 15th centuries and later, are generally believed initially to have caused mortality rates between 40 and 50%. The repeated pandemics caused a marked and permanent population crisis between 1350 to 1700.

The first historically reported pandemic attributed to Yersinia pestis began with the Justinianic Plague (541–544) also continued for around 200 years. Amply reported in numerous chronicles, the extent and severity is nevertheless yet to be decided.

To date, only one Yersinia Pestis strain from this pandemic has been reconstructed using ancient DNA. These aDNA-studies were carried on medieval individuals buried in 6th century Bavaria and published in 2005.

From literature, though, we know early medieval chroniclers noted the occurrence of the pestilence in a broader European context (Britan, Gaul, and Spain).

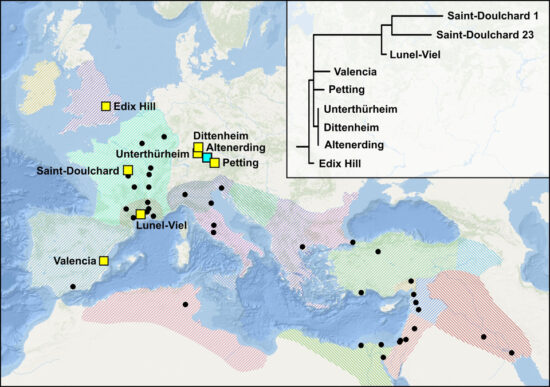

In a new study, the authors present eight “new” genomes from Britain, France, Germany, and Spain, demonstrating the geographic range of plague during the First Pandemic. The study, though, also shows a degree of microdiversity in the Early Medieval Period, which is parallel to that of the Later Middle Ages.

The point is that the studies have documented the same genome decay taking place in the Early as well as later Middle Ages. This decay indicates that while the pestilence mounted new “attacks”, it slowly changed. The scientists talk about microevolution and genetic diversity and provide insight into the persistence of the Yersinia Pestis between the 6th and 8th centuries.

Moreover, the authors have detected similar patterns of genome decay during the First and Second Pandemics (14th to 18th century) that includes the same two virulence factors, thus providing an example of potential convergent evolution of Yersinia Pestis during these large-scale epidemics. Thus hypothetically confirming the widespread distribution and lingering impact of the Early Medieval pestilence was akin to that of the Late Medieval Black Death.

Archaeological and Historical Context

The first genome mentioned in the article stems from a burial site near Edix Hil, close to Cambridge and close to a Roman road. The genome is believed to be related to the very first occurrence of plague and likely arrived in the English countryside in 544, following the outbreak in France in 543. This grave was surrounded by two double burials holding the remains of individuals also identified as plague- victims. These findings relate to the work of McCormick, one of the co-authors, using multiple burials in the same graves as indicators of a plague attack.

Besides, four genomes were identified in skeletal material from Central France as well as the Mediterranean Basin. Finally, another victim identified in a cemetery in Valencia fits well with the date of an outbreak in 546. This genome, however, presents a polytomy, suggesting the death of the individual took place at a later outbreak.

Individuals from Lunel-Viel in France seems to have been buried at an even later date, between 571 and 600, during which period Gregory of Tours records four and perhaps five outbreaks.

Also, individuals buried in a trench near Saint-Dulchard probably stems from an outbreak in Narbonne, dated 693.

Finally, the scientists have returned to the evidence found in the Bavarian burial grounds at Altenerding and Ascheim, identifying further plague-victims at Dittenheim, Petting, Unterthürheim, and Waging. These seem to relate to the very early strain found at Edix Hill.

“In the future, more extensive sampling of putative plague burials will help to draw a more comprehensive picture of the onset and persistence of the First Pandemic, especially on sites in the eastern Mediterranean basin, where not only is the Justinianic Plague reported to have started, but where also the eighth century outbreaks clustered according to the written records presently available. This will contribute to the comparative exploration of Y. Pestis’ microevolution and human impact in the course of past and present pandemics”, write the authors in a concluding remark.

In a supplement, the authors offer a detailed presentation of the archaeological and historical evidence in a published supplement.

SOURCE:

Ancient Yersinia pestis genomes from across Western Europe reveal early diversification during the First Pandemic (541–750)

By Marcel Keller, Maria A. Spyrou, Christiana L. Scheib, Gunnar U. Neumann, Andreas Kröpelin, Brigitte Haas-Gebhard, Bernd Päffgen, Jochen Haberstroh, Albert Ribera i Lacomba, Claude Raynaud, Craig Cessford, Raphaël Durand, Peter Stadler, Kathrin Nägele, Jessica S. Bates, Bernd Trautmann, Sarah A. Inskip, Joris Peters, John E. Robb, Toomas Kivisild, Dominique Castex, Michael McCormick, Kirsten I. Bos, Michaela Harbeck, Alexander Herbig, and Johannes Krause

PNAS. First published June 4, 2019

Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY).

FEATURED PHOTO:

Plague Victims. Credit: M. Schweissing. © Statssammlung für Antropologie, München