The history of medieval landscapes tells us of forests, groves and meadows sourced for wild edible plants and other fauna, which might help to survive despite fragile economic situations

“There [in the common land] they gathered palm hearts, and asparagus, and oregano and mint… firewood to take to sell in the city for its supply and for the ovens to bake bread”.

From: AGS. Consejo Real, Legajo 24, F. 1, Years: 1505 – 1511. As quoted by Emilio Martin (2019) p. 288

Few years ago, a group of biologists from Madrid [1] carried out a study of wild edible plants in Spain. Based on a review of 46 ethnobotanical and ethnographical sources from Spain, plus fieldwork in some provinces, they were able to register a total of 419 wild plants belonging to 67 families used as vegetables, fruits, beverages and seasoning.

Among vegetables, the most common plant is fennel, wild salads and watercress. Other common herbs are bladder campion, wild asparagus, and Spanish oyster thistles. All of these are still regularly consumed as part of scrambled eggs or omelettes. Or they are used as a green delicatessen in soups eaten during Lent or mixed in stews.

Among fruits, wild blackberries are mentioned the most often, as are the fruits from strawberry trees. But acorns from oak trees are less eaten although they have been used as an alternative in times of famine. To this group also belong sweet chestnuts and hazelnuts as well as wild apples, pears and plums. On the other hand, the fruits of hawthorn are seldom used today. The same goes for rose hips.

Many wild plants are used in beverages as teas or fusions, while certain wild fruits are commonly used to brew liquors. Also, there is the use of wild herbs as seasoning. Mentioned in the modern sources are oregano, rosemary, thymes of different varieties, mint, laurel, summer savoury, and wild onions. Finally, the survey mentions numerous sweet roots, which children used to search for and chew on as well as wild olives used for oil extraction and capers pickled in vinegar or brine.

From ethnographic studies, it appears that people consider these kinds of foodstuff as a famine food. Informants also refer to how wild plants were gathered and used during the Civil War in the 30s and the next decades. The question is, of course, whether the tradition to utilise such plants and fruits were a common practice in the Middle Ages? Or whether it was considered more of a famine food during this period?

As it happens, there are abundant late medieval sources, which can help us glimpse the role of wild harvests in an earlier time. The background is the events which took place after the conquest of Andalusia following the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212

Andalusia after the Conquest

From 1212 to 1252, the kingdoms of Castille-Leon and Aragon succeeded in conquering Andalusia. Only the Kingdom of Granada continued as a Muslim enclave until 1492. One of the consequences was a massive expulsion and migration of the Muslim population back across the Mediterranean. This led to a severe depopulation, calling for a vigorous effort to repopulate and settle the land, which was busy turning into a wasteland.

Thus, not only the reorganisation and with it the implementation of religious and juridical institutions in the newly conquered lands presented a significant challenge. Also, the repopulation was on the agenda. The influx of new settlers from the north, but also their continued subservience as well as defence demanded a serious deployment of administrative energy, as well as economic resources.

One of the first jobs was to get an overview of the land and its available resources. Hence, inspectors were sent to create registers, the so-called Libros de Repartimientos. Of these several are known. Best studied are the registers from Valencia, Murcia, Sevilla, Loja and Almeria. They tell us not only how the land used to be worked, but also how the new settlers were expected to go about the business.

Thus, the Libro de Repartimiento from Seville registered 258,611 ha land. Of this, 83% was registered as bread-land, 16% was covered in olive groves, and a mere 1% was either irrigated or laid out as wine-yards. Although irrigation-systems may have deteriorated because of the war, it does not seem likely that pre-conquest Andalusia should be thought of as a lush irrigated garden. This was serious farmland intended to grow and harvest the ubiquitous stable diet in the middle ages: grain and olives.

After the initial conquest, the land was partitioned to the people, who had taken part in the military venture. Initially, much of this took place as an equal distribution of land to settlers, who received it as quasi-owners with only a few obligations such as to work the land, keep the buildings intact and take part in the defence against Muslim intruders, invaders and pirates. Measures were also taken to prevent the selling back of the new settlements to absentee landowners or church institutions. Arguably, a new agrarian structure based on freeholding was obviously intended.

The partition thus resulted in a landscape characterised by numerous small and independent peasant-farms. More than 50% of the “new” holdings were small, using up 19% of the available land. Medium-sized estates constituted 47% and took up 68% of the land, while only 44 large estates tilled 12% of the land. All this land was distributed to royal retainers or people, who had taken an active part in the war. Although not all worked the land personally, very many did.

However, above and beyond this land, Andalusia offered ample un-appropriated land, some of which was also arable. This land was divided into so-called alfoces – huge districts, which were allocated to Andalusian town councils, nobles, and clerical orders and churches. Initially, this land was hardly cultivated, but during the 14th and 15th centuries we learn of numerous settlements instigated by such landlords and according to – sometimes – very different principles. Many of these projects aimed at setting apart vast areas for pasturing or – in the south – vineyards.

Also, despite the initial intentions of the royal government, land tended gradually to enter the market, and people with a long-term perspective soon began to acquire land cheaply laying the foundation for their future wealth. Accordingly, by the mid 14th century, the situation had changed dramatically. Now only 8,8% of the estates were small, 56% were medium-sized, while a staggering 35% of all estates were massive; the latter accounting for 67% of the land. One factor contributing was the rules of partible inheritance and communal ownership inside sprawling families. As time went by an initial plot of land simply became too small to nourish such clans. Another challenge was likely posed by the agrarian traditions and technologies, which the new settlers had brought from the North. Not always did they fit the sub-tropic climate of the South. Finally, there seems to have been a serious depopulation going on. We don’t have figures for the region before 1530. At that point an average number of people in the Cordoba region pr. km2 was 9 – 27 with an average of 11. This may likely have been halved around the mid 14th-century crisis, before and after the Black Death. With an average population density of 5 – 6 people pr. km2, and people living in nucleated villages and small towns, large tracts must have been experienced as virtually inhabited. A testament to this is the record of bear-hunting in the Cordoba region as noticed in the 14t century Libro de la Monteria [2].

Further, as the continued threat from the Kingdom of Granada and the Muslim Marinids, rulers of Marocco, took its toll, frontier warfare nourished a belligerent class of nobles, who tended to exploit their influential positions to gain control. The typical endgame was to enclose any un-appropriated or common land lying around waiting to be expropriated and used for cattle ranching. We know that it was mainly the city oligarchs and the administrative elite, who excelled in these practices.[3]

To sum it up: while the first settlers in the 13th century were mostly peasant freeholders, this had shifted at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century. Now, the land was exploited by large, often absentee, landowners, who were utilising vast tracts of former communal land for cattle ranching and transhumance. In the post-medieval world, this led to the well-known landscape of latifundia, which, nowadays, is even more extreme. As of today, 2% of the landowners in Andalusia – mostly large-scale cooperations – control more than 50% of the land, which is worked by more-or-less illegal North-African immigrants, while 30-40% of the landed population is unemployed (2011-2013) @.

One consequence was, of course, peasant uprisings or revolts, which are mentioned for the years 1463-67, 1471-74, 1503-07 and 1521-1523. Although an incomplete catalogue, it does tell us that living conditions were seriously deteriorating in a period when gradual repopulation was taking place. Another might have been more widespread use of “famine foods” and migration to the rapidly growing cities. We get a good sense of this new landscape in the laments quoted in a document drawn up in 1492 in which we hear that “the rich and powerful men, who were well-connected within the town and many of whom held offices in the town council, had enclosed their farms from boundary to boundary and – as far as the common lands were concerned – prevented the poor peasants from entering with their livestock. And had denied them access to other resources, such as the gathering of asparagus and truffles, the hunting of rabbits and birds, and the fishing of rivers and streams”. [5: p. 479]

Wild Landscapes in Medieval Andalusia

This varied use of the wild landscape in medieval Andalusia was recently explored through the study of the numerous written notarial documents stemming from court-cases and land-arbitrations from the 13th to the 15th century [6].

Through the careful reading of the texts, a fascinating picture emerged of the various species of trees, bushes, and other plants that were exploited by the local communities between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Such texts recorded coppices, bushes, groves in valleys, as well as clusters of poplars, willows and reeds near streams; next to these might be meadows. Also, singular trees and bushes were abundant. Trees mentioned were holly oaks, fig trees, quinces, wild olives, poplars, labdanum trees, kermes oaks, holm oaks, ash, pomegranates, mastic trees, strawberry trees, palms, Iberian pear trees, pine trees and willows.

Another landscape type was the “mata” – a flat expanse covered in bushes of a diverse kind. These might be covered in a mixture of myrtles, brooms, oleanders, caper bushes, shrub oaks, buckthorns, common hawthorns, lesser bulrush, phillyrea, tamarisks and blackberry bushes.

Abundant sources document that these different types of trees, bushes and plants played significant roles as sources for firewood, timber, ash for bleach, soap, tanning. Also, they furnished wood for tools – handles, wheels, lathes, spinning wheels and loams as well as cork used as containers for food (cork has preservative qualities against insects). Canes, reeds, and lesser bulrush were used for mates and seats of chairs, while palms yielded material for hats and baskets, and other plants were used for dying textiles.

Also, meadows were abundant, filled with wild plants, which might play a nutritional or medicinal role. Mentioned in the sources are bishop’s weed, cane, artichokes, lilies, asparagus, branched asphodels, wild beans, fennel, thyme and spurge flax.

Finally, wild fruits and vegetables apparently played an essential role in the Middle ages as they still do today, where wild asparagus, thistles and fennel is collected and used in the local kitchen.

On top of this evidence, we also find the occasional mentioning of flax, hemp, agaves, woad, madder and saffron, which were all harvested and sold as dyestuff in Cordoba.

These vegetal landscapes, which were characteristic of the southern regions of the Crown of Castile from the 13th to the 15th centuries, were of great importance for nearby settlements whose inhabitants used the wild vegetation as a resource for firewood, building materials, tools, dyestuff, tanning materials, as well as wild foods and herbs.

By mapping the different types of vegetation, it becomes clear that Andalusian peasants not only had access to but also exploited a wide-ranging portfolio of landscapes characterised by a very diverse collection of trees, bushes and plants in the uncultivated peripheries of settlements and villages. At least, these resources were available until the expropriation of the commons took off in the mid 15th century as part of the formation of the latifundia, which came to dominate the post-medieval landscape.

Another critical factor, though, is the increased notice these texts took of the diverse trees and plants. While the corpus mentioned three wild plant species in the 13th century, seven were mentioned in the 14th century, but an astounding 39 different species were mentioned in the sources from the 15th century. Does this reflect the numerical increase in written sources? Or might it – perhaps – be a reflection of the increased interest in the use of more marginal resources at a time, when the peasants were increasingly pushed towards economic despondency? And towards the exploitation of local crafts catering for the growing urban markets?

Sources and Notes:

[1] Ethnobotanical Review of Wild Edible Plants in Spain

By Javier Tardío, Manuel Pardo-de-Santayana and Ramón Morales.

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 152, Issue 1, 1 September 2006, Pages 27–71

[2] Libro de la Montería: Based on Escorial MS Y.II.19

By Alfonso XI (King of Castile and León)

Ed. and transl. by Dennis P. Seniff

Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies, Vol 8., 1983

[3] Peasants in Andalusia during the Lower Middle Ages. The State of the Question in the Kingdom of Seville.

By Emilio Martín Gutiérres

In: Imago Temporis Medium Aevum vol 3, 2009, pp. 249 – 289

[4] Land: Access and Strugles in Andalusia, Spain.

By Marco Aparicio, Manuel Flores, Arturo Landeros, Sara Mingorría, Delphine Ortega and Enrique Tudela

Produced by: Educación para la Acción Crítica (EdPAC); Grupo de Investigación en Derechos Humanos y Sostenibilidad – Cátedra UNESCO de Sostenibilidad de la Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya 2012 -13

[5] The Medieval origins of the Great Landed Estates of the Guadalquivir Valley

By. E Cabrera

In: The Economic History Review, Vol 42, no. 4 pp. 465 – 483.

[6] The Vegetal Landscape of the southwest of Cordoba: a sample of the natural environment of Andalusia in the Late Middle Ages

By Javier López Rider

In: Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies

Published online 09.02.2018

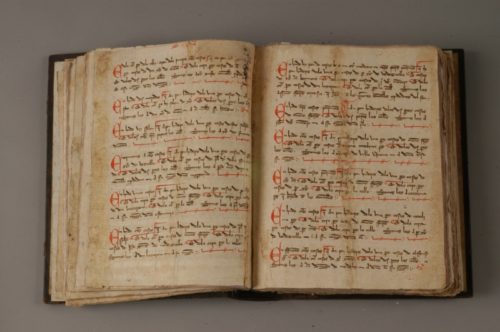

FEATURED PHOTO:

View from the Castle at Almodovar. Notice the “wild” landscape along the river © The Villa Company