The history of the 12th-century Scandinavian church and the formation of the Norwegian and Swedish provinces is interwoven with the murder of Thomas Becket.

It is a historical tour-de-force among Scandinavian historians and theologians to debate the relationship between the 12th-century Scandinavian kings and the contemporary clerical elite(s). A long list of historiographical studies of the different positions and arguments published since 1916 have shown the palpable political biases fielded by various scholars and historians.

We shall not review these positions here. Instead, the question raised has to do with some curious parallels in England and Denmark between the events leading up to the murder of Becket. And the different ways the inherent conflicts played out. And ultimately, how the Danish King and ruling elite looked upon the events in Canterbury in December 1170.

The Background

Until 1103 the Scandinavian churches were under the jurisdiction of the archbishops of Bremen-Hamburg. Following the canonisation of St. Cnut in 1100, a Danish Archbishopric was set up in Lund. Later, in 1153 Norway got their own Archbishop in Nidaros, with Sweden establishing an Archdiocese in Uppsala in 1164. This new organisational structure of the Scandinavian provinces followed a diplomatic sending of a papal delegate, an Englishman, Nicholas Breakspear, to Scandinavia. Despite the ongoing conflict, Breakspear was nevertheless instrumental in bringing some order into the formal church organisation. When Breakspear returned to Rome, he was elected Pope. We know of him as Adrian IV; and as an avid opponent of The Holy Roman Emperor, Frederic Barbarossa.

At this time, the Archbishop in Lund was Eskil, a scion of one of the ruling families in Denmark (the Thrugots).

In Eskil’s youth, a civil war raged in Denmark. After a decisive battle at Fodevig in 1134 – where a great many bishops were killed – Eskil was appointed bishop in Roskilde. Later, in 1137 he was appointed Archbishop in Lund. Eskil was an enthusiastic supporter of Bernard of Clairvaux, the Cistercians, Pope Alexander III (the successor of Adrian IV) and – we may presume – Thomas Becket. In these matters, however, Eskil had to toe the line with the Danish King Valdemar and his foster-brother Absalon, the later Archbishop in Lund, who for political reasons were semi-aligned with Barbarossa and his antipopes, Victor IV and Victor’s successors, Paschal III and Calixtus III.

Eskil must have been married before his ecclesiastical career eventually took off. Late in his life, we hear of two grandsons, who were direct descendants (through the marriage of Eskil’s daughter to a grandson) of the Danish King, St. Cnut († 1080). As witnessed by their names, Karl and Knud (Cnut), these two boys had valid claims to the Danish throne (Karl being the name of their great-uncle, Charles of Flanders, who was murdered in Bruges in 1127 in the same manner as his father, St. Cnut had been killed in Odense in 1084). The name Karl, of course, reflected the dynastic links of the Dukes of Flanders to the Carolingians. At the end of his life, Eskil was witness to and perhaps even involved in a revolt orchestrated by the two youngsters. In 1177 he was either forced or chose to resign to live out the rest of his life at Clairvaux.

Controversial Archbishops

Eskil was – as Becket – a controversial figure among the 12th century Danish and European elite. On the one hand, Eskil was known for his friendship with Bernard of Clairvaux and his continued effort to establish Cistercian abbeys in Scandinavia. On the other hand, Saxo wrote of him as a cantankerous, old man with whom the Danish King was not on particularly friendly terms, to say the least. In 1161, Eskil left Denmark to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Returning to Europe, he spent the next seven years in France – in Paris, Reims, and Clairvaux. During this period, he excommunicated two bishops installed in Denmark by the antipope, thus souring the collaborative relationship between the Danish King and the German Emperor. At the end of this exile, Eskil was even taken prisoner by some of the Emperor’s men. Somehow, he was freed in time to return to take part in the events leading up to the coronation of the young scion and heir apparent, Cnut VI, and the translation of the saintly remains of Cnut Lavard, the father of Valdemar, the Danish King. Known as the “Double Feast in Ringsted”, it was celebrated on the 25th of June 1170, ten days after the coronation at Westminster of the young King Henry. However, while Thomas Becket as Archbishop was side-lined at the events in Westminster, Eskil chose – despite his aversion to the sanctification of Cnut Lavard – to officiate at the Danish coronation and translation in Ringsted. Later, in 1177, Eskil was tainted by the rebellion of his grandsons and had to resign from office, leaving the Archbishop’s throne to Absalon, to spend the remains of his life at Clairvaux.

Becket, on the other hand, famously took a more confrontational stance by staging a reconciliation at Fréteval with king Henry II, while at the same time feuding with and excommunicating (among others) the officiating bishop at Westminster, the Archbishop of York. Ultimately, these acts questioned the “legality” of the said coronation, probably angering Henry II to the point of instigating the murder in Canterbury in December.

Likely, the intentions to coronate younger sons in both Westminster and Ringsted in 1170 were driven by a dynastic intent to avoid a replay of the respective civil wars in England and Denmark in the first half of the 12th century. The agendas were to secure smooth successions. In both cases, however, the legality was at stake. In Denmark, it was settled by confirming the coronation through the parallel translation of the sainted grandfather of the young King. In Westminster, it was carried through as an act of defiance by gathering the King’s faithful part of the English Ecclesiastes to confirm the de facto shunning of an Archbishop, in whom everyone (even the Pope) had lost confidence.

In the 12th-century, Scandinavia was no backwater. Lively contacts to France were established to the Cistercians and the Victorines, while diplomatic and political connections and networks were established and nourished through letters, sendings, and face-to-face meetings. The elite not just knew of each other; they knew each other from letters and personal encounters. Thus, both Becket and Eskil were present at Sens at the consecration of Stephen from Alvastra as the future Archbishop of Sweden. It has been suggested Stephen was of English origin. Also, a letter has been preserved from Becket to the Danish King, probably penned by Herbert of Bosham. Other correspondence between John of Salisbury – another of Becket’s supporters – and Absalon has been preserved.

Likely, the rumour of the events in Canterbury in 1170 arrived at the Danish shores inside months, if not weeks. The question is: what was the Danish and Scandinavian “take” on the events?

Thomas Becket in Medieval Denmark

In the church at Sdr. Nærå near Odense, one of the very earliest pictorial renditions of the events in 1170 was painted. Although fragmentary, the murals seem to represent three scenes: Thomas Becket leaving Sens in France, returning to Canterbury, and finally, the martyrdom of the Archbishop. The frieze was painted in an early Romanesque church from c. 1100 to which a western part was added c. 1200 in the form of a brick tower including an upper gallery or pulpit intended for the Lord and his family. This extension may well have been built by William of Winchester (1184-1213), grandson of Henry II by his daughter Matilda and Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony. Matilda and her sisters were the first promoters of the cult of Becket. In 1202, William (Matilda’s son) married Helena, a sister to the Danish King Cnut VI and was given extensive land near Sdr. Nærå as her dowry. William’s coat of arms has been cautiously identified in a fragmented battle-scene in the murals.

Interestingly enough, these murals constitute the sole artistic evidence of the early veneration of St. Thomas Becket in present-day Denmark (apart from the later evidence of liturgical celebrations). It should be noted that three stories of early miracles seemingly touched upon Danes. But whether these were widely known is questionable.

While Danish churches outside Scania thus seem to have been curiously devoid of early Thomas-Becket-reminiscences, this was not the case in Scania.

The oldest witness derives from the church in Gumlösa, which was consecrated in 1191 by Eskil’s successor, Absalon, in the presence of the Norwegian Archbishop Eirik Ivarsson from Nidaros and the Swedish Bishop Stenar from Växjö. According to an old inventory, Thrugot Ketilson, the founder of the church, donated a number of relics to the church. Among these were some very prominent relics: a piece of the cross, a piece of the stone on which the cross was raised, a piece of the stone covering the grave, a piece of the vessel (scutella), from which the Lord ate, and some hair of the Holy Mother, some of her clothes and that of John the Baptist … and a relic from “Sancti Thomæ Cantuariensis Archiepiscopi & Martyris”. Interestingly enough, the collection also held a relic deriving from Bernard of Clairvaux. Unfortunately, the list does not specify the bits and pieces of the saints. And yet, it is an impressive collection, 92 in all.

Further, the church is in itself remarkable. Built of burnt bricks, it constitutes the first such building in Scania. Studies of the brickwork have shown a marked affiliation with that of Sorø, which was built by Absalon. It is considered likely the same architect was present. The building in Gumlösa is Romanesque with a narrow nave and a square chancel, covered with groin vaults, and a tower at the west end. At the east end, the entrance to the chancel is marked by a triumphal arch constructed around two pillars mirroring the columns in Dalby, Hildesheim and elsewhere. Such columns were deemed to represent Jakin and Boas, flanking the entrance into the Temple of Solomon.

The baptismal font is particularly interesting. Carved in sandstone by a mason named Tove, it stands on a plinth featuring dragons or worms being captured by lions. The basin features the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Adoration, the Circumcision and the Baptism in the River Jordan. The artist is called the Lyngsjö-master (Lungsjömestren) and is believed by some to have been responsible for several fonts in other churches, among those a font in Lyngsjö depicting the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. The artistic qualities of this font have been said to refer back to inspiration from the milieu surrounding Henry the Lion married to the daughter of Henry II, Matilda (see above). The same artist may also be responsible for a famous capital from Dalby, featuring a series of Danish kings and their queens, beginning with St. Cnut and his queen Adele of Flanders. Dalby was a very early royal centre and pantheon. A brother to St. Cnut was buried there.

The combined testimony of the prestigious company present for the consecration, the architecture and construction of the outstanding church-building, the artistic qualities of the baptismal font, the impressive collection of relics, and the name of the donator leads us to ponder whether Thrugot Ketilsen was a kinsman of Eskil, who had accompanied him on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem and later to France, where he acquired the opportunity to collect the huge assembly of sacred souvenirs, which he later donated to the church at its consecration?

Lyngsjö Church is another of those very early churches built in the eastern part of Scania in the 12th century. Somewhat earlier than Gumlösa, it was built of fieldstone in the 1140s with a broad western tower, a nave, a square chancel and an apse (later demolished). Lyngsjö was at the centre of the hundred and held the thing. The church is known for its golden antependium, with thirteen scenes displaying Mary on her throne with Christ in her lap. The design differs from the more rough and glittering golden altars known from Jutland. A comparable antependium may be seen at Grosscomburg.

Also, as said, the church holds a prominent piece of art – a baptismal font carved with a rendition of the murder of Thomas Becket. The carvings show three scenes beginning with Henry II giving the order to a knight (Reginald FitzUrse), who in the next scene is seen together with his comrades walking purposefully up to the alter to murder Becket, while Grim stands by trying to shield the Archbishop. Meanwhile, a dove descends on a chalice, probably reflecting on the way in which some biographies tells that his spilt brain was scooped up and brought to the high altar; (as pointed out recently by Anne E. Duggan). At the back of the font, we find the presentation of the keys to St. Peter, the coronation of Mary, and the Baptism in Jordan. The plinth features ornamental carvings of snakes being caught by a lion, a ram and an angel.

To the extent that Becket was venerated in late 12th century Denmark, the evidence points to a few select places, primarily located in Eskil’s own backyard, Scania.

Thomas Becket in the Norwegian context

“Words cannot express the many benefits the oft-named King conferred upon his people, the good he did while he governed them, by enacting laws and relieved the poor, by diligent preaching and by the example of his holy life. He had many trials and tribulations to endure from the people until at length, he could not oppose the multitude of evils. Thinking the moment required it, he withdrew into Russia till the Lord should deign to find a time, suitable for him to fulfil his desire and purpose. Let no one suppose that this most stalwart and steadfast champion of Christ was subject to human weakness, that he retreated for fear of martyrdom”.

(from: Passio Olavi, as quoted by Haki Antonssen)

We don’t precisely know when the cult of Thomas Becket was established in Norway. We do know, though, that the early propagation was owed to Archbishop Øystein Erlendsson (†1188), who early on after his election in 1161 embraced the Gregorian Reform Movement in its 12th century Cistercian version. Unfortunately, a pretender to the Norwegian throne, Sverre, emerged victorious in 1184. During this civil war – from 1179 to 83 – Øystein lived in exile in England, from where he excommunicated Sverre. On his return – and likely inspired by the rebuilding of Canterbury – Øystein initiated the construction of an ambulatory akin to the new corona at Canterbury. Also, the liturgy of Becket, created by Benedict of Canterbury, was very early on incorporated in the Ordo Nidrosiensis. Some believe that a statue on the Western Front of the cathedral is of Thomas Becket.

Moreover, the story of Becket seems to have echoed through the Passio of St. Ólafr, Passio Olavi, written either by Øystein himself or at his instigation. In his take on the story, Østeyn adopted the motif of Becket’s flight – as it was reframed by his supporters as a prolegomenon to his martyrdom – to the story of Olaf Haraldson fleeing to Kiev to return two years later, where he was killed at Stiklestad in 1030.

To this should be added a remarkable reliquary built like a house with dragonheads. The reliquary is preserved in the stave church in Hedalen, which has been dated dendrochronologically to 1165. The reliquary is dated to c. 1230 and shows the actual scene of the murder, with the Adoration above. The gable ends show figures of St. Olaf, St. James and St. Peter. The Reliquary from Hedalen is one of thirteen dragon-mounted reliquaries preserved in Norway. These shrines were probably moulded over the shrine of St. Olav in Nidaros, which Snorri describes as formed as a house, decorated with heads of dragons.

Hedalen was not consecrated to St. Thomas. This, however, was the case with the churches in Tynset, Feiring and probably Filefjell.

Thomas Becket in a Swedish Context

The early impact of Thomas Becket on the church in Sweden is also noteworthy.

The first evidence is from Vallentuna and stems from a missal, the Vallentuna Book (Liber Ecclesiae Vallentunensis). Dated from 1198, the 29. of December is clearly marked in the calendar by red, reading Thome Martyris. Added to this evidence should be the reliquary preserved in Trönö church. Made in Limoges, it nevertheless features the “Nordic” detail with dragons sprouting from the roof at the gable.

Finally, a baptismal font preserved at Nora in Ångermanland, ca. 400 km north of Uppsala should be mentioned. Not well preserved, it seems to copy some of the motifs from Lyngsjö (the part with the descending dove). At Nora, however, not just the Archbishop’s crown is cut off; rather Becket is decapitated. The font was sculpted at Gotland by the anonymous master called Calcarius. Known for more than twenty works, Calcarius is not known to have used the motif elsewhere.

Becket in a Scandinavian context

Scandinavian church politics in the 12th-century were fraught with internal as well as external conflicts. First of all, it was deemed vital for Eskil and his Cistercian party to avoid the sliding-back of Scandinavia into the hands of the Bremen-Hamburg; and being forced, accordingly, to embrace the lukewarm German attitude towards the question of the balance between the regnum and the sacerdotum. Having lived through the events from 1075- 1122, Bremen carefully nourished the truce. The Cistercians would have none of this.

Secondly, Eskil was – probably inspired by the English church organisation – also mindful of preserving his status as primo inter pares among the Norwegian and Swedish Archbishops. And finally, he was closely affiliated with the Cistercians in France and their reform movement, of which Becket was the star par excellence.

And yet, Becket came – apart from a few distinct places primarily in Scania – to play a near-invisible role in the artistic programme of the Danish Church. The two new archbishoprics in Trondheim and Uppsala, as opposed to this, seemed to welcome and nourish the new cult at quite another level.

Then, how did the Danish King and his men think about Becket?

Saxo Grammaticus, who wrote his extravagant history of the Danes, Gesta Danorum, between 1080-1216, may give us an inkling. In his take on the events in the 12th-century, he provides us with a salutary lesson, likely forged out of the history of Henry II and Becket. In his story about the friendship of King Sven Estridsen (1047-1076) and Bishop William of Roskilde (1048-ca. 107, we hear of how the King had a group of his men killed in front of an altar while attending Mass in the Cathedral in Roskilde. This led to the bishop excommunicating the King while calling him a “bloody butcher of men”. After this, a scene followed in which royal retainers sought to kill the bishop to avenge the excommunicated King by holding a sword to the bishop’s neck. Luckily, though, the King repented; and after a proper ritual of humiliation of the King, mirroring that of Henry’s at Canterbury, the two men were finally reunited in friendship. To the extent, claims Saxo, The two men – King and Bishop were buried side by side in the Cathedral in Roskilde. Initially, the story was thought to mirror St. Ambrose’s chastice of the Emperor Theodosius. Recently, however, Haki Antonsson have argued, that the exempla should be read as a veiled comment on the martyrdom of Thomas Becket.

To Saxo – the mouthpiece of Absalon and his King, Valdemar – the story of Becket ended all wrong. Real politics was about balance, arbitration, and cunning. And not high principles. An yet, Becket was a man to venerate. As Absalon did, when he consecrated the church in Gumlösa in 1191. At that point, though, Valdemar had been dead for more than ten years, and William was about to marry the sister of Cnut VI, the new king. And – perhaps – rebuilt and decorate the church at Sdr. Nærå.

Becket might have been venerated in Norway and Sweden. But not particularly in Denmark.

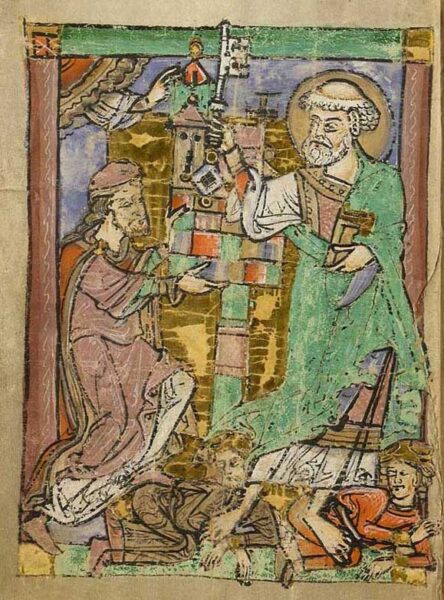

Featured Photo:

Thomas Becket at Sdr Nærå in Denmark © National Museum and Arnold Mikkelsen

SOURCES:

Becket’s Cap and the broken Sword. Jacques de Vitry’s English Mitre in Context.

By Anne J. Duggan

In: Journal of the British Archaeological Association (2020) Vol. 173, pp. 3-25

Blod og vann fra Canterbury

By Arne J. Larsen

In: Årbok for Universitetsmuseet I Bergen 2012

Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery.

A Study of the Emergence of Cults and Native saints in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Lund and Uppsala from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries.

By Sara Ellis Nilsson.

University of Gothenburg 2015

Eystein, Thomas Becket and the Wider Christian World.

By Anne J. Duggan

In: Nidaros Domkirkes Restaureringsarbeider: Ed. by Kristin Bjørlykke, Øystein Ekroll, Birgitte Systad Gran and Marianne Herman.

Nidaros 2012

Kansleren Radulfs to bispevielser. En undersøgelse af Saxos skildring af ærkepispe- og pavestriden 1159-1162

By Michael H. Gelting

In: Historisk Tidsskrift (1980) vol 80:2

Lyngsjömästeren: En tysk stenhuggare i Skåne omkring 1200

By Frans Carlsson

I: Fornvännen (1970) pp. 318-327

The cult of Saint Thomas Becket in the Swedish Church province during the Middle Ages

By Bertil Nilsson

In: International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church (2020).

The Legend and Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket Painted in the Church of Sønder Nærå, Funen, Shortly after His Death in 1170

By Ulla Haastrup

In: Hafnia. Copenhagen Papers in the History of Art (2003) Nr. 12.

The Lives of St Thomas Becket and Early Scandinavian Literature

By: Haki Antonsen

In: Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni (2015) Vol. 81 No 2, pp. 394-413

The Liturgical Commemoration of Thomas of Canterbury in Scandinavia. The first thirty Years, 1173-1203

By John Toy

In: Of Chronicles and Kings: National saints and the Emergence of Nation States.

Museum Tusculanum

The Ocatagonal Shrine Chapel of St. Olav at Nidaros Cathedral

By Øystein Ekroll

Thesis

Trondheim2015

To the question of the (Danish) Royal House and the Spread of Thomas Becket Cult in Denmark,

By John H Lind,

ICO,

Iconographisk Post 1982: 3, pp. 38-39.