Swords as symbols of sovereignty are known from the 11th century and onwards. However, careful examination of new evidence shows the precursors belonging to the 10th-century Ottonian dynasty were typical Viking swords

Swords of the 10th century as symbols of sovereignty in the Ottonian Dynasty. On the precursors of the Imperial Sword and its imitated types

[Schwerter des 10. Jahrhunderts als Herrschaftszeichen der Ottonen. Zu den Vorläufern des Reichsschwerts und zu dessen Imitationsformen]

By Mechthild Schulze-Dörrlamm

In: Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2012, Vol. 59, No. 2

Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums

2014

ABSTRACT:

In a remarkable and fascinating piece of research, Mechthild Schulze-Dörrlamm has recently turned her attention to some hitherto “forgotten” drawings of royal swords

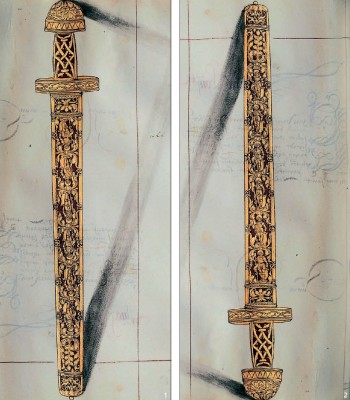

One of these drawings shows the so-called St. Maurice Sword, which according to later reports was presented to Otto the Great in Magdeburger Cathedral right before he died in 973. Detailed examination of the drawing has shown that this sword must have been a Viking sword, type V.

The other illustration is found in an illumination from Benevento from 985 – 98. The drawing shows his son, the emperor Otto II at his coronation carrying a luxurious Viking sword, type S. Both weapons seem to have been fitted with two-part pommels with cross guards as well as sheaths with short chapes.

At the end of the 10th century, the ceremonial swords changed their outlook. Now, they became fitted out with single-part pommels and sheaths made totally out of gold-leaf. The oldest example is the bejewelled sword presented to Henry II at his coronation in 1002, which is depicted in the Regensburg Sacramentary.

Another example of this stylistic shift can be seen in the ceremonial sword from Essen, which was a fully functioning mighty Viking sword of type X (Jan Petersen’s Typology). Made in France, this sword carries scars from battles as well as continuous sharpening. After being presented to the Essen Convent in AD 993, it was redecorated with gold and jewels and fitted with a new glamorous sheath. This sword is believed to have been part of the regalia belonging to the Emperor, Otto III. It some point it was presented to the nuns in Essen as part of a memorial foundation for Otto II. Legend has identified this sword as the one used by Otto I at the Battle of Lechfeld, where another legend tells us the army declared him “emperor” after the victory. The Essen sword was a precious heirloom.

________

Exactly how these now golden-sheathed swords were carried by the emperors – personally or in front of him at processions – is not precisely known. However, the sheath of the imperial sword now kept in Vienna is believed to belong to the reign of the emperor Henry IV and used at his coronation in 1084. This long gold-leafed sheath shows 14 kings and emperors in full regalia. In order for these to be seen, the sword must have been carried in front of the emperor with its point upwards. This sword provided the prototype for later regal swords and their use in the coronation processions.

The article explores this shift from the early form of ceremonial swords of “Viking” heritage to the new and more visually appealing ritual swords of the Salian emperors. This shift is traced not only through a study of depictions of swords long gone, but also other extant swords, for instance, the “Viking sword” kept in the treasury of the cathedral in Prague.

However, the overwhelming pertinent question of why the Ottonian Emperors paraded Viking swords as part of their “regalia” remains to be explained. Perhaps they were just mighty swords fitted out in the fashion of their specific time? For instance, we cannot know how the pommels in the two new drawings of the lost swords were decorated? With Scandinavian Animal styles or more continental and Christian ornamentation as that which was discovered in a ship-burial in Haithabau (form the 9th century). We also know that Vikings wielded swords with single pommels after the turn of the millennium. The Norsemen seem to have been well aware of fashion trends.

Further, it might be pertinent to ask whether such a thing as a “typical” Viking sword ever existed (we still do not know where they were made). The challenge here is of course that the only swords, which have not been found in graves in Scandinavia are those from Essen and Prague plus a few stray finds in rivers, for instance in Normandy.

Perhaps a sword was a sword in the 10th century until it became an heirloom and was placed in a grave or gifted to a saint. What the present article shows is that these swords at some point became ritual artefacts in an Ottonian context at the turn of the millennium. Apparently, this shift later gave rise to the use of such swords as ceremonial and ritual artefacts in the symbolic performance of sovereignty.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Picture of an emperor, probably Otto II, crowned by angels. The emperor is carrying a sword with a Viking pommel and fitted with a metal tip. From the archive of the Beneventen Archbishop 985 – 87. Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica, Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 9820