Uppåkra in South-Western Sweden presents a remarkable continuity. For more than a thousand years, the place functioned as a cultic, commercial and elite centre.

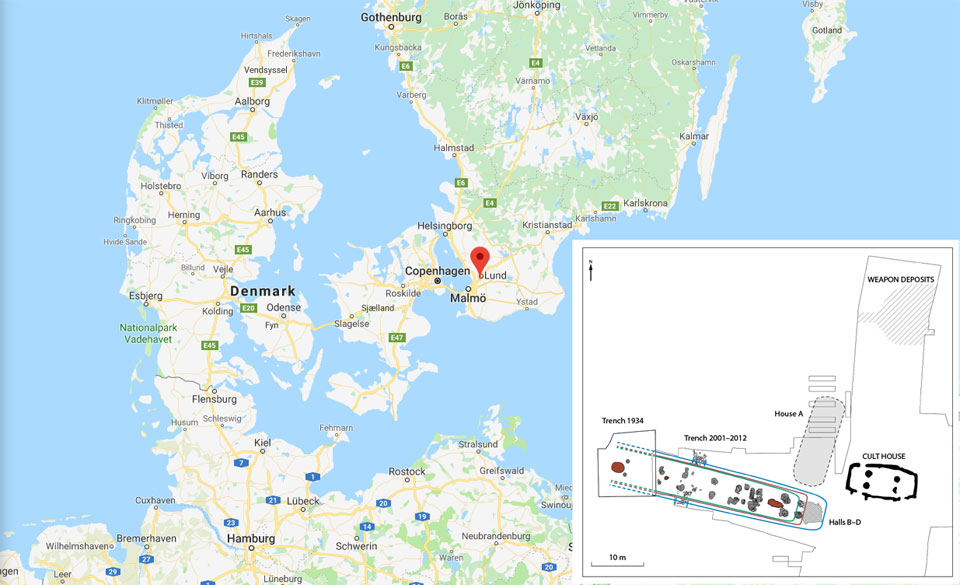

Uppåkra is located inland just outside the city of Lund on a height overlooking a flat and fertile plain. Today a small and insignificant village, it remains one of the most prominent central places in the first millennium Scandinavia.

The proto-town was inhabited from 100 BC and until a relocation took place to the city of Lund in the late 10th century. Although less than 1% of the place has been excavated, more than 28.000 finds have been registered since 1996, when archaeologists and metal-detectors began to investigate the site, which is believed to have covered 40 ha.

The first excavations were undertaken beneath the floor in the present church. This exploration revealed an early Christian burial as well as the find of a remarkable early medieval encolpion from late 10thcentury Germany. The reliquary in the form of a crucifix fits well with the date of the grave.

More fascinating, though, was the discovery of the sacral centre of the earlier Uppåkra. This building complex, located to the south of the present church, consisted of a hall positioned next to a what has been interpreted as a temple. Excavations afterwards uncovered a succession of buildings, which have been dated from the Early Roman period and until ca. AD 1000. With occupation layers up to two metres thick, it has been possible to document both continuance and historical events.

The Temple

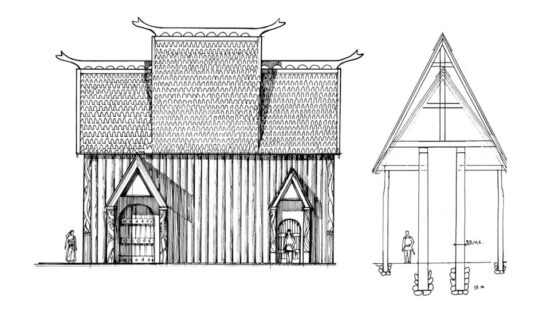

The structure of the temple was nearly identical from c. AD 100 – 1000. Designed with a clay floor, a centrally located fireplace, it measured ca. 7 x 15 metres. The house itself was built with stave construction and supported by massive posts. Four posts in the corners as well as four additional posts in the interior held up the roof. Initially, the house may have been utilised as a smithy, but the finds around the house – and especially in the postholes – soon indicated the house for centuries played a different role. With its huge posts, it may have reached high. The discovery of an iron door ring deposited in a posthole ca. AD 500 – 600 indicates the hall was carefully locked and set apart as a judiciary and sacred place for the cult. Perhaps the four knobs on this ring, reflect the four central posts in the hall? And might they refer to the four main gods (venerated to this day in our calendar): Tiw, Odin, Thor, and Frigga?

At the beginning of the migration period, ca. 400, the house had been in existence for several hundred years. At this time, the place had already been surrounded by numerous sacrifices of weaponry, while guests had helped embellish. During the next several hundred years, people who visited the site may also have donated the multiple gold-foil figures, which may have been used as tokens and sacrificial votives. Perhaps, they were affixed to the posts with honey and wax? Another group of finds from the same period were a cache of surgical tools, possibly indicating the connection between healing and cult. Finally, two extraordinary vessels – a two-coloured bowl from the Black Sea region and a metal beaker with gold-foil ornamentation, dated to c. 400 – 500 were discovered carefully deposited beneath the floor around c. 550. Other glass-shards were found, indicating feasts were organised inside the house. The gold-foil decoration of the beaker was embellished with serpents, human figures, and quadrupeds, and shows affinity to the bracteates found nearby.

The high and impressive cultic house may have been a visual rendition of Valhalla, Odin’s Hall. Or it might be a northern version of a Mithraeum.

Outside, the archaeologists discovered the remains several caches of destroyed and sacrificed weapons. Most of the weapons – or rather fragments of them – were found in a hollow depression to the north of the small house. The bits and pieces stem from swords, lances, spears, shields, helmet(s), and harnesses. The first large cache of weapons can be dated to ca. 210 – 530, with older outliers. Either, the length of the period witness to the continuity of cultic practices during several hundred years; or – more likely – the weapons had originally hung inside the hall. During one of the rebuildings, the cache became deposited outside some time in the 6th century. Later weapons are solitary finds, and were presumably haphazardly spread around the place until ca. 700.

It has been argued that Uppåkra primarily functioned as a garrison complete with a cultic centre.

The Halls

From ca. 400–900 the small cultic house was a close neighbour to a series of nearby halls, one built upon or next to the other. Several of the halls had been burned down – the first ca. 400. Inside the house, the remains of three individuals were found. Less than a century later, a cache of human bones as well as some gold objects in the form of bracteates were deposited inside these ruins. At about the same time another large building was torched. There, at least five human beings were burned to death and left. A third fire has also been recorded.

These fires leave us with a conundrum. Apparently, halls at Uppåkra were burned down three times inside 200 years. In the same period, however, the cultic house was left in peace. If the site was a garrison, the destruction of the halls might well have been the result of local feuding or even war. It appears any invaders would leave the cultic house intact. The social organisation of the migration period has been characterised as a “cleptocracy within a martial society”. As such the social fabric was permeated with violence and martial virtues as well as infused with a sense of history and genealogy. Halls or abodes for people might be burned down. And people might die inside these burning buildings. Yet, the attackers would not burn down the “house of the Gods”. Afterwards, if the attacks were repulsed, the survivors might deposit the vanquished weapons of the defeated on the field. And leave their ancestors to rot inside the burned-down buildings as a form of mortuary memorial.

A Feasting Culture?

Recently, a metric study of the hulled barley grain found in different locations at Uppåkra has identified a distinct variation in the size.

While the grain in the neighbourhood dedicated to workshops was of the smaller type, large, high-quality grain was discovered in the hall buildings. Apparently, the grain was carefully sorted during the Migration period, AD 400 – 550. During this period, Uppåkra was especially affluent, and people seem to have participated in lively contact with wider Europe.

Handling grain was already in place during the early phase of the settlement and that it remained for centuries. This study indicates that the affluence otherwise seen at the regional centre Uppåkra from an abundance of high-status objects could also include agricultural wealth, with extensive access to high-quality grain.

Why would this sorting take place? One explanation is that seed grains were collected and centrally preserved. Uniform grain size permits even seeding. In an Iron Age Economy, the agrarian economy would be organised around small infield-outfield systems calculating with high yields near the houses. Large seeds also provide faster-growing plants since nutrition (starch) in the seed is more abundant.

Another explanation, however, is the use of the large hulled Barley for the brewing of beer or porridge. While bread might be baked from a mixture of differently sized grain, beer and porridge benefits from high quality grain.

A detailed study of zooarchaeological material from Uppåkra has shown that pigs, sheep, and goats were raised locally, while cattle was walked- in from a wider area. The closer to the great halls and the cult house, the consumption of meat was more abundant. Also, bones from the neighbouring villages indicate that the meat-rich and more delicious cuts had been exported elsewhere, presumably to the cult centre.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Silver beaker and Bowl from Uppåkra © The Historical Museum in Lund

VISIT:

Welcome to Uppåkra – an iron Age Town

Stora Uppåkravägen 101

Staffanstorp

Sweden

The Historical Museum at Lund University

Krafts torg 1

Lund, Sweden

WEBSITE:

Barbaricum – Uppåkra och skånes järnålder

READ MORE:

A Ceremonial Building as a “Home of the Gods”? Central Buildings in the Central Place of Uppåkra

By Lars Larsson

In: Schriften des Archäologischen Landesmuseums. Wachholtz. 2011,Band 6, pp. 189 – 206

Från romartida skalpeller till senvikingatida urnesspännen. Nye materialstudier från Uppåkra.

Ed by Birgitta Hårdh

Uppåkrastudier 11

Acta Archaeologica Lundensia no. 61

Continuity for Centuries. A Cremonial Building and its context at Uppåkra, Southern Sweden.

Ed. by Lars Larsson

Uppåkrastudier 10

Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, No. 48

Expressions of Cosmology at the Central Place of Uppåkra, Southern Sweden.

In: Dying Gods – Religious beliefs in northern and eastern Europe in the time of Christianisation herausgegeben von Christiane Ruhmann und Vera Brieske.

Series: Internationales Sachsensymposion 2013.

Stuttgart: Niederssächsiches Landesmuseum Hannover 2015

Uppåkra’s Political Situation in the Migration Period

By Birgitta Hårdh

In: Life on the Edge: Social, Political and religious Frontiers in Early Medieval Europe.

Neue Studien zu Sachsenforschung, Vol 6. Ed. by Babette Ludowici.

Brauschweigisches Landesmuseum 2017

The Powerful Ring. Door rings, oath rings and the sacral place.

By Marianne Hemr Eriksen

In: Viking Worlds. Thins, spaces, and movement. Ed. by M. H. Eriksen, U. Pedersen, B. Runerberget, I Axelsen and H. Berg. Oxbow, 2015, pp. 73 – 87.

Barley grain at Uppåkra, Sweden: evidence for selection in the Iron Age

By Mikael Larsson

In: Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2018, Volume 27, No. 3, pp. 419–435