In the Early Middle Ages, the Vosges were regarded as a wilderness – by elites, poets and priests. However, the ideas about how to live in and utilise this wilderness were contested.

One day, King Guntram (c. 532 – 592) hunted through the woodlands in the Vosges and discovered traces of killed aurochs. And when he pressed the forest keeper more closely, asking who presumed hunting in the royal forest, the man betrayed Chundo, the King’s chamberlain. Relying upon this hearsay, the King ordered Chundo to be seized and led in chains to Chalon-sur-Saône. When both were present before the King, a bitter argument took place. Chundo denied ever having committed the crime he was being charged with, and the King decided to judge the matter with trial by combat. The chamberlain then appointed a nephew of his as a stand-in in battle. When the two men stood face to face in the field, the young man hurled his spear at the forester and pierced his foot so that he fell backwards. Then he drew his dagger, which hung at his belt and tried to cut the fallen man’s throat. Instead, the young man was wounded in the stomach by a knife-thrust. In short, they were both laid low and died. As soon as Chundo saw what had happened, he dashed the church of St Marcellus. The King shouted that he must be captured before he set foot on the holy threshold. They caught him. He was tied to a stake and stoned to death. Afterwards, the King was sorry that he had lost his temper and that for such a petty offence, he had recklessly killed out of hand a faithful servant her could ill spare.

(Based on the translation in: Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Translated with an Introduction by Lewis Thorpe. Penguin 1974, Libri 10.10, p. 559)

The Landscape

In a geological sense, the river Rhine runs through many landscapes. One of these is a long stretch dominated by the Vosges Mountains, the Vosges foothills and the fertile Rhine plain below. From Basel and Mulhouse to Karlsruhe, the Vosges extends over 300 km from the north to the south and has an average width of 50 – 60 km. The upper Rhine basin is flanked to the east by the German Black Mountains in Alemannia and Swabia, and to the west, Alsace, Lorraine and the Vosges in Franconia.

This landscape is rich and diverse, covered by wild peaks of barren high sandstone reaching up to 1424 metres, dark forests, and cultivated vineyards on the slopes in the foothills.

To the north, the landscape is traversed by smaller rivers fanning into the Mosel and the Saar, creating a landscape of wetlands, the so-called “rieds” (from the Alsatian word “rieth”). Feeding the River Ill and, ultimately, the Rhine, these smaller rivers were never quite so hydrologically manipulated as the larger rivers used for transports. Even today, they offer some beautiful spots, allthough the foothills and plains are densely populated in the valleys. Historically, the ridge appeared to be challenging to get across, and most traffic was forced to make way through the Belfort Gap, also called the Burgundian Gap, to the south, forging a way towards Mulhouse. However, the many river valleys did offer the possibility for people – if need be – to settle higher up and to wander back and forth through the mountains.

Early Medieval Wilderness

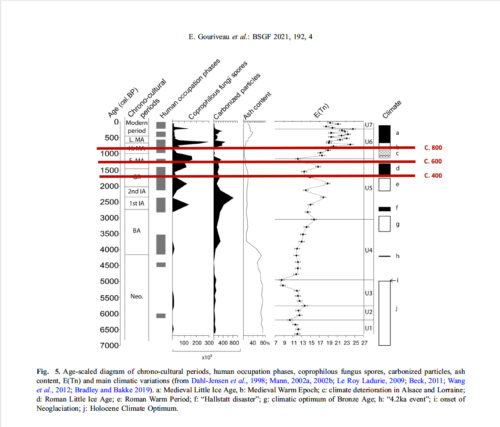

The region has been described as the most intensively studied in a recent overview of palynological studies (studies of pollen profiles) carried out in the Vosges. The results from several sites were recently fused into a combined diagram. The main conclusion is the total absence of cultivation (Cerealia) during the migration and early medieval period until AD c. 850. At the same time, the region appeared to have been covered in forests dominated by beeches and fir trees (Fagus et Abies) and mixed with alder and hazel (Alnus and Corylus). At any time, the cover has laid between 60 and 80%.

Even if the landscape appears homogenous, distinct differences may be found. While hazel and oak might have been prominent in the south, pine and birch dominated in the north (as it still does) due to the acidic earth. Plantations caused the modern cover of spruce

Deforestation took place in the Roman period, after which the landscape was once again left to its own devices until the expansion led by the great Carolingian monasteries in the 8th and 9th centuries. In the north of the Vosges near the castle of Waldbeck, the area appears to have been totally abandoned between 540 – 670 with its cooler and moister climate, and again during the wars from c. 790 – 1000 between the heirs of Charlemagne and the ravages led by the Vikings and the Magyars. Another indicator, the percentage of ceramic shards from different periods, tells a similar story. In the early Middle Ages, the number of shards fell to a third of what had been the case in the Gallo-Roman period, to rise again in the high and late Middle Ages.

These palynological and archaeological records, together with other paleoenvironmental studies, fit well with archaeozoological research carried out at Birgelsgarten in Ostheim north of Colmar, which was excavated in 2008 by the Pôle d’Archéologie Interdépartemental Rhénan. This rural settlement was located on the edge of a terrace consisting of loess, bordering on wetlands at the river Fecht. Thus, the excavated site was located right on the border between the hills and the plain. Around 2500 animal bones were retrieved from layers attributed to the Early Middle Ages. Most of the bones derived from domestic animals. However, in pit 3070-3325, from the late 7th to the early 8th centuries, almost a thousand bones were excavated, of which the remains of the game represented 16% of the bones identified.

Moreover, these bones derived from species rarely encountered in Merovingian Gaul: European bison, aurochs, and moose. Further, the pit held the remains of several stags and a wild boars. The pit has been interpreted as the remains of a sojourn of an aristocratic elite engaged in hunting, as is described in the story about Guntram quoted above. The scientists carried out isotopic studies of the remains and found that the bison had roamed both the dense forests and the more open landscapes, while the aurochs preferred the forest (Putelat, 2016; Sudhaus 2015; Gouriveau 2021)

Also, this characterisation fits well with a study of the overall plant diversity (biodiversity) carried out at the castle of Waldeck in the north of the Vosges during the last 6600 years (from the Neolithic to modern times). During periods of abandonment – c. AD 540 – 770, and again c. 790 – 1000, the biodiversity index fell from 22 to 12%, reaching the neolithic baseline, indicating that there was a marked correlation between the presence of settlements with people engaged in silvi-pastoral activities, the abundance of spores from Coprophilous fungi (spores from cow-dung) and a more open biodiverse countryside. With the highest level reached in c. 1750, followed by gradual abandonment, these silvi-pastoral forms of land-use appear to once again degrade or disappear altogether.

From an archaeological perspective, Vosges was reduced to a favoured hunting ground in the Migration period and the early Middle Ages. This description fits well with the shifting literary and religious landscapes presented in poems and other texts from the migration and early Merovingian period.

The Dissolution of the Roman Villa Landscape

In the 4th century, the poet Ausonius (c. c. 310 – c. 395) wrote a poem, Mosella, describing the landscape of Late Antiquity with its central feature, the civilised Roman villas located up and down the river Rhine and its tributaries. An echo of these poems can be found in the letters of Sidonius Apollinaris and others, who wrote extensively about their loci amoeni and the good life in the civilised countryside. Here, the patrician owner of a villa might spend his time looking backwards to see the “sharp rocks” mounting “upwards and piercing the clouds” where the “rough swelling cracks reach to the stars”. Nevertheless, he could also look down pensively and calmly upon the murmuring rivers with their benign and lush banks offering abundant gardens, pleasures and enjoyable harvests.

All this, though, was fast disappearing in the mid-6th century, when the Merovingian poet Venantius Fortunatus wrote a poem to Gogo, who was part of the inner circle of the Austrasian (Merovingian) court, where he served as the mayor of the palace, tutor to the young Childeberth and later regent during his childhood. Fortunatus had befriended Gogo in Ad 567 at the wedding of Childeberth’s parent, the Merovingian King Sigebert I and Brunhilda, a Visigothic Princess, an event which Fortunatus also took part in and described. Apparently, Gogo continued to be part of his circle of friends, and around the same time as the wedding, Fortunatus wrote one of four poems to him. The one which we are concerned with here opens with the words, Nubila quae rapido perflante Aquilone ueniti, and is numbered 7:4 (Leo, 1881)

In this poem, Fortunatus speculates on where he might find Gogo. The poem reads:

Clouds that come with the swift-blowing north wind,

Hanging where the celestial wheel turns,

Tell me, where does dear Gogo pass his days,

What peaceful thoughts occupy his serene mind:Is he lingering near the shores of the wavy Rhine,

to draw in the net, heavy with salmon, from the waters?

Or does he stroll along the vine-clad Moselle where a gentle breeze tempers the burning day, where the vine’s shade cools the midstream heat, and where the wave is refreshed by the river’s flow;Or does he sweetly ramble along the Meuse, where crane, goose, and swan abound, fruitful in triple measures (with bird, fish, and boat);

Or does he keep near the Aisne, where it breaks against grassy banks, where pastures, meadows, and fields are nourished by its waters? Or does he approach the rivers Saar, Scarpe, Scheldt, Somme, or Seille, taking its name from salt and flowing to Metz? (1)

Or does he range more in the summer through woods and meadows, with spear and net, binding beasts here, slaying them there? Do the Ardennes or Vosges resound with the bellowing of stags, the cries of goats, elk, and aurochs as does the forest echo with the deathly chill of arrows? Or does he confront the mighty bison amid the field with his spear while the bear, the wild horse, and the boar defer not death?

Or does he till his fields, ploughing the scorched fallow,

While the bull groans under the yoke on his neck?Or does he sit happily in the palatial aula,

where the school, assembling, applaud him with love’s enthusiasm? Where is he together with his friend Lupo recalling the laws of mercy, and with equal counsel administering mild honey, to feed the needy, to provide solace for the widow, and to enjoy the love of Christ the King?I pray to you, oh winds, who run and return, bear tidings for the sake of Fortunatus.

(Own translation 2024)

It appears that Venantius Fortunatus skilfully posits a list of natural scenic settings in this poem, among which the villa only features in its absence. Where might we seek Gogo? On the riverbanks, fishing or fowling? Or sailing up and down the rivers flowing through the countryside? Or in the forests, hunting large and truly wild game? Or in the field cultivating the land? Or may we find him in the palace conversing and governing with his friend Lupus while delivering merciful justice and offering solace to those in need and the widows? The answer is – as they say – not blowing in the wind. We may be sure Fortunatus weighs in on the final option. The poem may give us a sense of a wild(er) landscape filled with a natural abundance of wild beasts, fish and fowl. However, in the end, Gogo is placed in the civilised setting at Siegebert’s court.

We get a glimpse of Gogo’s lifestyle from the archaeological excavations at Erstein south of Strasbourg, where a partly destroyed Merovingian cemetery was discovered in 1999 near the Rhine, holding 248 graves with 256 interred individuals. The burial ground appears to have been used between ca. 500 and 600. The graves – some of which were placed in mounds – were lavishly fitted with grave goods, indicating the elite character of the settlement. For instance, cloisonné fibulae were found in 35 burials, while 120 held combs made of antlers. Unique was the weaver’s blade, the scales of a goldsmith, and the wooden box decorated with thin stamped appliques of copper alloy.

In 56 graves, weapons were found. Of these, 16 held long swords, all discovered in “Morken” type chamber burials. In ten of these burials, the dead were also laid to rest together with a scramasax and a lance, in two cases with only a scramasax and in three graves, only with a lance. In ten cases, the long sword came with a shield. Sometimes, the hilt could be identified and made of ash or antlers. Only seven of the 16 swords were fitted with metal pommels. Only in one grave was a combat knife found.

The women’s graves were also marked out by important grave goods such as fibulae, both smaller at the neck and the larger pairs attached to the lower part of the garments. While rings and earrings were rare, pearls and spindle whorls were ubiquitous. On many pieces of jewellery, a residue of well-crafted textiles was preserved. The materials were, as expected, linen and wool. No traces of colouring could be detected.

In 111 of the graves, leftovers from the burial meals were discovered in ceramic containers, glassware, and bronze dishes of meat, eggs, and fish.

Local history has it that a Roman military encampment was located on the site, which was later taken over by the Merovingian royalty. Subsequently, local historians placed the ruins in the Chateau de Bulach (Schloss Osthausen) gardens two km south of Erstein. In 2014, archaeologists, however, identified the remains of a substantial settlement 350 metres from the necropolis, arguably the largest settlement in Alsace from this period. The place dates back to the Iron Age. Thus, the Merovingian period offered a glimpse of a large and well-structured site with numerous houses, cellars, grain silos, wells, and sunken huts. A burial ground to the north indicates the presence of a funeral church.

In 830, Irmengarde, wife of Emperor Lothair, founded a convent in the neighbourhood. The site was called Villa Regia Herinstein. This villa was mentioned for the first time in 817 when Louis the Pious divided his empire among his three sons. Afterwards, he and his son Lothair went hunting in the area, and afterwards, Louis donated the manor to his son together with sixty peasant farms and their families. The Vosges itself may have been relatively empty of people after ca. 500, but the river valleys around the Ills, the Rhine, and the Moselle continued to be inhabited.

Erstein is located c. 40 km north of Birgelsgarten at Ostheim, where the pit was excavated, holding the remains of the many large and wild beasts (Putelat, 2016).

A spiritual landscape?

“At that time, there was a great wilderness called Vosagus, in which there was a castrum that had long been in ruins and that an ancient tradition called Anagrates. When the holy man came to that place, he settled there with his followers despite the harsh desert of solitude and the habitable places interspersed with cliffs. He was content with a meagre consolation of food, mindful of the saying that man does not live by bread alone (Deut 8:3) but is sated by the word of life, overflowing with bountiful food, which, whosoever shall taste, shall never know hunger anymore.” (Translated by Marron 2012, p. 15). In a more terse version, we read that “When the holy man arrived there, although the place was rough, on account of the expanse of wilderness and the impediment of rocks, he settled there with his followers, making do with a small food allowance” (Bully 2017, p 121).

Was the Vosges a spiritual landscape? In Fortunatus’ poem, we find a whiff of a paradisical echo floating through the air in the form of the warm and blessed wind, the gentle shades and the beloved afterlife, connotations which may also be found in the earlier “Mosel-Poem” by Ausonius, and in Suetonius’ villa-ideology. Also, the motif of the cleansing and life-giving waters inherent in the riverine topology offers subtle hints of the eternal Christ. However, this gentle resonance of both the Paradisical rivers and the Second Coming is nevertheless quietly subsumed in a landscape which arguably had taken on a less civilised form in the new Merovingian world where Fortunatus resided. Fundamentally, the world was not overtly civilised but brutal on the fringes. Fortunatus offers us a glimpse of this uncivilised “wilderness”, from which the heavenly rivers led towards the episcopal cities and their royal palaces, where heavenly justice was administered according to the gospels.

Neither was this the case put forward in the writings of Jonas of Bobbio when he wrote about the life of the Irish monk Columbanus (c. 543 – 615). Born and educated in Ireland, Columbanus, with twelve friends (apostles), set out as a missionary from Ireland to the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms. Here, the saint founded abbeys in first Annegrey in 591, and later Luxeuil in 594 and Fontaine in 602 in the southern foothills of the Vosges in the Haute-Saône, in the valley of the river Breuchin, a tributary to the Lanterne and eventually the Rhône.

Columbanus was remembered in a series of texts, foremost his vita written by Jonas of Bobbio, the final abbey, for which Columbanus and his friends were responsible. Although we are invited in his writings to see the mountains, hills and forests in the Vosges as the home of the “wild beasts, bears, aurochs, and wolves that haunted” Annegrey, Luxeuil and Fontaines, these mighty animals were lumped together with the pagans. We read how

“it happened that the holy man was walking through dark remote paths in the wood […]. And while he was turning this over in his mind, he saw twelve wolves approaching and surrounding him from right and left […]. And before he had gone far, he heard the voices of many Suevi, wandering in these remote areas and who at that time were committing robberies in this region […]. Again, he left his monastery and, entering the vast wilderness through a very long road, found an immense rock with steep cliffs. It was covered with sharp rocks, making it inaccessible to men”

(Bully 2017, p. 122).

And yet, in this wilderness, harmony was to be found. Thus, we may read how Columbanus escaped from a pack of wolves, expelled a bear from its den, and commanded another bear to leave a fallen stag’s carcass. And in another charming vignette, we read that Chagnoald told Jonas how he:

“Often saw Columbanus, when he was taking a walk in the wilderness and was devoting himself to fasting and prayer, how he would frequently summon wild animals, beasts, and birds which would come immediately at his command, and he would pet them gently. The savage animals and birds, rejoicing and playing with great delight, would then jump about, just as puppies fawn upon their masters. And the man above said he had often seen the little animal, which people commonly name a squirrel, called down from the tops of high trees, taken in his hand and put on his neck where he let it crawl in and out of his habit”.

(Quoted from (O’Hara 2018: 237)

We may ask whether Annegrey (591) or Luxeuil (594) were true wildernesses. As to Luxeuil, it had been and still was a seizable provincial town renowned for its hot and cold baths. Recent excavations have shown that the remains of a funerary church at Luxeuil, St. Martin, show that the settlement reaches back into Late Antiquity and that the church was part of a Roman house. A number of the burials date back to the 4th century, suggesting there was a Christian community as early as that.

Likewise, the surroundings of another Romanesque church overlooking the hamlet of Annegrey from the Mont Saint-Martin have yielded evidence of a late Roman pagan cult with Diana at its centre and other enigmatic finds from the Merovingian and Carolingian periods.

Likely, the mother institution at Annegrey could also turn up to be anything but located in a non-cultivated wilderness, as Marron speculated in his thesis in 2012 (Marron, 2012, p. 94), and which has been suggested in a later review (Bully et al.n2017). These authors suggest that the topos of the arid and unhospitable desert were more of a rhetorical construct than a vivid reality.

Unfortunately, however, these archaeological surveys of the history of the broader landscape in the Vosges do not consider the overall result of the palynological studies mentioned above, which reveal a notable contraction of evidence for cultivation in the 6th and 7th centuries. On the other hand, the location of the Columbanian monasteries at major Roman roads and routes signifies that the possibility of creating a favourable setting in a semi-civilised and settled area for their harsh and ascetic lifeform may have been overtly advantageous.

To conclude, the well-known tropes from the early Egyptian hagiographical writings, the desert and the barren wilderness, were necessary for the idealised creation of the loci sancti, where the original peaceful relationship between man and beast might be resurrected. That this rhetorical setting came first to be located next to a minor access road reaching up into the higher hills at Annegrey, where we hear locals bought food laden on horses or carts to the newly settled band of brothers, was no coincidence. Nor was it a witness to the cognitive dissonance that the later monastery at Luxeuil was placed near a somewhat busy regional road between east and west and amid a significant Roman town. More than anything, these texts’ desert and wilderness were rhetorical tropes intended to lead civilised and decadent people from their greedy and worldly lifestyle and into the imagined desert of a penitential and ascetic lifeform.

A Useful Landscape?

Evidently, Fortunatus and Jonas wrote from different perspectives. For Fortunatus, the wilderness was the scenic background for the civilised palatial residence where governing might. It should unfold in the capable hands of the elite courtiers and surrounded by the lush trappings of global pleasantries such as teardrops of balm from En Gedi, aromatic herbs from Arabia, pepper and nard from India, dates from Africa and precious and various stones from far away (Bully et al., 2017). For Jonas in his writings, the wilderness, on the other hand, was a distinct place needed to create a break from this civilised and decadent lifestyle of the elite

Evidently, Fortunatus and Jonas wrote from different perspectives. For Fortunatus, the wilderness was the scenic background for the civilised palatial residence where governing might. It should unfold in the capable hands of the elite courtiers and surrounded by the lush trappings of global pleasantries such as teardrops of balm from En Gedi, aromatic herbs from Arabia, pepper and nard from India, dates from Africa and precious and various stones from far away (Bully et al., 2017). For Jonas in his writings, the wilderness, on the other hand, was a distinct place needed to create a break from this civilised and decadent lifestyle of the elite

The question remains: What – if anything – were the Vosges good for in terms of economy and exploitation?

First of all, the low-lying and forested mountainous ridges were

a significant hunting ground for the Merovingian elites scouring for the impressive games to serve at their banquets. Although hunting was not yet a royal prerogative (Goldberg, 2020), we get a sense in the writings of Gregorius how a king might indeed engage in envious infighting with his courtiers when engaging in masculine pursuits in the forests. Doubtless, aurochs with their horns were coveted pieces of game that might be used for drinking horns and gifts, such as those discovered in the grave at Sutton Hoe. Apart from the need to practice weaponry on moving targets, hunting was a preferred pastime and played a significant role in staging the Merovingian elite and their power positions.

The forest, however, was also suitable for other “products”. At the brink of the new post-Roman Europe, St. Remigius (c. 437 – 533), who was bishop in Reims, owned a large tract of woodland in the Vosges, which he called Cosla and Gleni from the nearby rivers. Here, he built dwellings for people resettled from Behren so that they might provide a measure of pitch each year to supply the religious houses in Rheims. In his testament, we read that the pitch was intended to line wine barrels (2).

This pitch belongs to a group of special products made for sale in the peripheries of European forests and mountains for millennia. Any forester would know how to settle away from the brinks of rivers subject to occasional violent floods. Instead, the foothills held small plots of tilled fields, orchards with their beehives, groves of chestnuts, vineyards, and enclosures for shielding animals in wintertime. Also, the highlands and the plains provided food for flocks of sheep and pigs, while semi-feral cattle and horses would have roamed the woodlands. Further, the forest would be gleaned for wood, nuts, mushrooms, herbs, wild fruits and berries, and furs from trapped animals and exploited for timber and the production of charcoals. Finally, rivers and lakes would be fished. For Columbanus and his men, using the local lakes on the Plateau de Mille Etangs, with its more than 800 lakes, must have been a bonanza. All these riches, carefully balanced and exploited as part of a silvicultural regime, would, in good times, yield more or less refined products, which might be marketed to the prominent religious institutions established from the end of the 6th century and central to the administrative structure and later organisation of the semi-feral wilderness.

Conclusion

We might well ask to what extent the Vosges was a wild, impassable and dense wilderness in the Early Middle Ages from ca. 500-700?

Reading the paleoenvironmental scientists, there is no doubt as to the answer. Until the end of the 4th century, the Gallo-Romans lived in the landscape, providing many forestry products to the cities and towns. During the political and migratory upheavals after c. 400, the Vosges were gradually emptied of people, and after the climatic events in c. 536-41 and following the Justinian plague, the mountains appear to have been more or less abandoned until c. 670, after which a period of relative growth set in. Nevertheless, after ca. 790/800, due to wars and raids, people largely abandoned the upper northern ridges. During these periods, we primarily hear about the Vosges as a true wilderness and a dedicated place for elite hunting of the mighty bison, aurochs, and boars.

Nevertheless, the role of the Vosges as a setting destined for spiritual solace among the early Irish missionaries appears to have been a myth, which primarily played out in the minds of Columbanus and his followers. As best they could, they tried to find their loci sancti on the fringes of the remains of the civilised world.

NOTES

(1) The names of the listed rivers and tributaries to the Rhine are not certain (see Leo 1881, p. 156. See also: Caesar Belgae. ‘Satis’ (‘Sabis’?): de verdwenen rivier, by Armand Sermon. In: Sermon Armand: Caesar tegen de Oude Belgen. II. Aduatuca, Eburones, Ambiorix. Mens & Cultuur 2015.

(1) The Will of St. Remigius is preserved in two versions, a shorter from the 9th century and a longer from the 10th, have been for a long time considered a forgery. Arguably, however, new studies of the names of 81 slaves and tenants have unequivocally shown that the testament is based on an original. (see: Testamentum Remigii. Les noms des servi, des coloni et des parentes du testament de l’évêque Remi de Reims. By Wolfgang Haubrichs, Gérard Bodé. In: Nouvelle revue d’onomastique (2010) Vol 52 pp 155-185).

EDITIONS:

Poems. Venantius Fortunatus.

Edited and translated byMichael Roberts.

Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library

Harvard University Press 2017

Venanti Honori Clementiani Fortunati. Presbyteri Italici. Opera Poetica. Recensuit et emendauit Fridericus Leo.

Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Actorum Antiquissimorum Tomi IV Pars Prior.

Berolini 1881, p 156 7:4

SOURCES:

Negotiating the landscape. Environment and Monastic identity in the Medieval Ardennes.

By Ellen F. Arnold

University of Penn Press 2013

Ausonius, Fortunatus, and the ruins of the Moselle.

By Chris Bishop

In: Memories of Utopia. Of Histories and Landscapes in Late Antiquity.

Ed. By Bronwen Neil and Kosta Simic.

Routledge 2021

What did the Merovingian palace look like?

By Jip Barrevald. Post 06.05. 2023 Leidenmedievalistsblog.nl

Bégeot, Carole, Pascale Ruffaldi, , Anne-Véronique Walter-Simonnet, David Etienne, Anne-Lise Mariet, and Emilie Gouriveau (2019): Les Vosges: des forêts et des chaumes.

In: Bépoix, Sylvie/Richard,

Hervé (eds.): La forêt au Moyen Âge. 301–314. Paris.

Mensa in Deserto: Reconciling Jonas’s Life of Columbanus with recent archaeological discoveries at Annegray and Luxeuil.

By Sébastien Bully and J.-M. Picard.

In: Transforming landscapes of belief in the early medieval insular world and beyond. Ed. By Edwards Nancy, Ní Mhaonaigh Máire, and Flechner Roy.

Brepols (2017) pp 119-143

L’armement dans les tombes de guerriers de la nécropole mérovingienne d’Erstein (Bas-Rhin)

ByThomas Fischbach

In: Archéologie médiévale (2016), vol 46

Goldberg, Eric J.

In the Manner of the Franks: Hunting, Kingship, and Masculinity in Early Medieval Europe.

The Middle Ages. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

From the Neolithic to the present day: impacts of human presence on biodiversity in the sandstone Northern

Vosges (France).

By: Emilie Gouriveau, Pascale Ruffaldi, Loïc Duchamp, Vincent Robin, Annik Schnitzler, et al.

In: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France (2021) vol 192, no 4

Politics and Power in Early Medieval Europe. Alsace and the Frankish realm, 600 – 1000.

By Hans Hummer

Cambridge University Press 2005.

Palynological research of the Vosges Mountains

(NE France): a historical overview

By Pim de Klerk

In Carolinea (2014) Vol 72, pp 15-39.

Vivre dans la montagne vosgienne au Moyen Âge : conquête des espaces et culture matérielle, Actes du colloque de Gérardmer-Munster, 30, 31 août et 1er sept. 2012

Ed by Charles Kraemer and Jacky Koch

Nancy, Presses univ. de Nancy – Éd. univ. de Lorraine, 2017

In his Silvis Silere: The Monastic Site of Annegrey – Studies in a Columbanian Landscape.

By Emmet Marron (PhD)

Department of Archaeology, School of Geography and Archaeology, National University of Ireland, Galway 2012

Jonas of Bobbio and the Legacy of Columbanus: Sanctity and Community in the Seventh Century

By Alexander O’Hara

Oxford University Press 2018

Une chasse aristocratique dans le ried centre-Alsace au premier Moyen Âge: l’apport de l’archéozoologie à la connaissance du site d’Ostheim Birgelsgaerten (Haut-Rhin, France).

By Olivier Putelat and Thierry Logel.

In: Peytremann, Edith (ed.): Des fleuves et des hommes à l’époque mérovingienne. Territoire fluvial et société au premier Moyen Âge (Ve–XIIe siècle). Actes des 33e journées internationals d’archéologie mérovingienne, 28–30 septembre 2012, Strasbourg, pp. 255–270. Dijon 2016.

‘The description of landscape in the poetry of Venantius Fortunatus: The Moselle Poems’,

By Michael Roberts,

In: Traditio 49 (1994) 1-22.

The Humblest Sparrow: The Poetry of Venantius Fortunatus

By Michael Roberts

University Of Michigan Press 2009

Early Medieval Landscapes and Societies in European Lower Mountain Ranges:The Vosges and Jura, 6th–7th Century

By: Nicolas Schroeder

In: The Early Medieval Countryside in the Migration period. Ed by

De Gruyter 2024

Holocene Vegetation and Land Use History in the Northern Vosges (France)

By Dirk Sudhaus and Arne Friedmann

In: Quaternary Science Journal (2015), Vol 64 No 2 2015, pp 55 -66

On the Vita Deicoli and the Legacy of the Columbanian Monasticism at the Turn of the First Millenium.

By Steven Vanderputten

In: Traditio 76 (2021), 157–184

Friendship in the Merovingian Kingdoms. Venantius Fortunatus and his contemporaries.

By Hope Williard

Arch Humanities Press 2022