The remains of the last of the two hydroelectric dams at the River Selune were finally dismantled in 2022, leaving the landscape to recover. But unfortunately, the restoration is hampered by multiple interests and no clear agenda.

The River Sélune is an 86 km long river in the Manche department in Normandy and drains more than 1000 km2. It has its outspring near Saint-Cyr-du-Bailleul and empties into the bay of Mont Saint-Michel near Avranches. Until the free flow was hampered at the beginning of the 20th century, the countryside featured the typical agricultural scene of Northern France with rolling hills and hedgerows galore – the bocage landscape.

In a description from 1858, we read that the river landscape used to “abound in woods mingled with partial clearances of well-cultivated corn-land, through the midst of which winds the river, flashing in glittering pools until expanding into a broad estuary it meets the sea, which borders the horizon”. La Manche was and is a rural area where the dominant agricultural system is mixed between dairy, seasonal pasture, and the growing of fodder and grain. Although the traditional hedgerows have been largely dismantled, the remains may still be found in the landscape.

Thus, the river would eventually flow into Europe’s largest tidal basin by meandering through the hilly landscape, the deep gorges and the hinterland forests. With the rivers Sée and the Couesnon, the Sélune would become part of a wide marshy delta of considerable ecological significance.

However, since 1914 and 1927, the Sélune’s free flow has been hampered by two of the largest hydroelectric dams in Europe.

Background

Since time immemorial, people have settled on higher ground, yet near lakes, rivers and estuary landscapes. Collecting water for people and animals was always a significant consideration. Later, the use of running water for operating mills and transporting goods and people came in handy. Further, the intensive use of rivers for irrigation was known from prehistory, as was the redirection of water for constructing canals, moats or fishing dams. Finally, the fertile deltas and marshy forelands would entice people to settle on the hilly promontories.

Nevertheless, the scale of redirection and control of rivers by constructing single dams, reservoirs or cascading water flows in the 20th century took the regulation of our watercourses to a new level. Today, less than a third of the world’s largest watercourses flow freely. A recent survey (Habel 2020) reckons that more than 50% of the world’s large rivers have “lost their hydromorphological and ecological continuity”.

However, although dam projections continue, major initiatives primarily seek to demolish them and restore river courses to their former glory. In the EU, the European Water Framework Directive issued in 2000 has acted as a prompt in this direction. While some countries – for instance, Denmark – have hesitated to fulfil their obligation, others, such as France, have taken a more active stance.

The Demolition of the Dams

One such project was the plan from 2009 to demolish the two large dams at the river Sélune in Normandy. The two dams erected at the beginning of the 20th century had radically changed the landscape and the ecology. However, when the government 2009 decided to dismantle the two dams, the main argument was to allow salmon to – once again – spawn upriver. Considered to be the third-best French river in terms of “Salmon Potential”, the Sélune is a classified river for Atlantic salmon, sea trout, brown trout, European eel, pike, sea lamprey and river lamprey. More precisely, the argument was not to restore the entire riverine landscape to its former glory as a robust ecosystem. Instead, the argument was to further the local economy by restoring the river as a rich playground for European anglers. Although the vision was presented as an idea of “rewilding” or “re-naturalising” the river, the aim was minimal. Soon, the local inhabitants came to see the projected dismantling of the dams as primarily intended to further the upper-class anglers as opposed to the local fishermen, who built huts on the lakesides and used to fish in the lakes created by the dams. Most of all, though, they came to feel deprived of their “landscape.

La Paysage – The Landscape

Soon, the restoration project was met with a vocal local opposition focusing on this structural divergence. At the centre was the idea of what “the landscape” – in French, la Paysage – the Sélune was and should be. Together with the concept of “Terroir”, this idea of a “Paysage” continues to play a significant part in the history of the mentality of modern France; as was apparently the case along the banks of the river Sélune.

To understand the conflict, we thus have to note that the people living along the river and next to the lakes did not envisage their landscape as particularly unique. On the contrary, insofar as they had thought about it, their landscape was considered ordinary as opposed to the landscape in the Bay of Mont-St-Michel. Unlike this tourist trap, the upstream and hinterland landscapes were not considered particularly important. Hence, many informants believed that removing the dams and the lakes would gender a bland and banal landscape of “nothingness” of mud and invasive plants. Vocally, they feared living in a “dead” and “empty” landscape in the future. This position was voiced to counter the initial arguments for the demolition of the dams, namely the rewilding of the river in its former glory.

At this point, local officials entered the fray with an “official” alternative. According to local planners, the new valley should be turned into a zone of tranquillity and a “leisure valley”. No longer arguing for a “nature reserve” or “sanctuary”, the valley should rather offer a haven for outdoor tourism. One concern often voiced in interviews and talks was the official fear of the potential overgrowing of the landscape leading to the disappearance of “open views”. Thus, while the local inhabitants feared becoming “homeless”, the planners envisaged a gardened and controlled future of modernity filled with tourism income. As opposed to this position, those carrying out the physical dismantling of the dams (the Normandy Water Agency) argued together with NGOs to “make the river wild once again”, albeit primarily meaning letting the salmon spawn upriver. Unfortunately, we now know their vision was lost to the “outdoor tourism paradigm”.

Different Interests

Soon, the nearly vertical slopes along the riverbed were expropriated by planners and sports enthusiasts of a different ilk. Trails for mountain bikers and runners were built into the slopes offering new and splendid challenges. At the same time, anglers entered the fray reconstructing the riverbeds to lure the salmon and other lesser fish swimming up the river, while the planners sought to accommodate the kayaking people and mitigate the conflicts between the different kinds of outdoor tourists. Also, the planning of events began to feed the imagination of the local managers.

To some extent, these interventions were hampered by another group, the farmers, who likewise tried to appropriate the land, adopting it (if possible) for grazing purposes (both seasonal and year-round) while working the relatively flat and fertile fields alongside the new riverine banks. One fear they voiced was that the new vegetation would soon spring up and hinder cultivation. Also, some farmers were anxious that the “weeds” the naturalists passively let burst forward would spread into their cultivated fields. Some farmers complained that controlling these pests was impossible, even when using pesticides. As farmers had abandoned 10-15% of their land since 1980, their concerns were carefully registered by the local administration and allowed to curtail the passive rewilding otherwise envisioned.

Finally, the hunters experienced a setback. Formerly, the wild boars had been held back on the northern side of the river by the dams or lakes. Now, the new landscape allowed the animals to swim across the river, exploring the farming land and forests to the south and making the hunting grounds less easy to exploit.

Missed opportunity?

While the “Wild West” takeover of the riverside for sports and entertainment began, the practicalities of emptying the lakes and rebuilding the riverbeds and slopes used up the energy of the engineers and conservationists. In practice, this led to a period of passive rewilding, and after 2017 a mosaic of new plant communities colonised the banks and wetlands. Although “agricultural” species dominated, a rich and diversified pool of species did come about. According to the biologists studying the riparian assemblages of plants which cropped up along the restored riverbanks, they differed markedly from the “older” riparian landscapes of the tributaries. This passive restoration led to the conclusion that it would create a mosaic landscape offering up different profiles of plant communities in the riverine landscape.

However, a discussion about the consequences of the continuing eutrophication appears not to have been raised. Consequently, the environmental restoration remains unfinished, and as yet, the future of the drained space – 200 ha in all – has not yet been decided.The question thus remains: to what uses should this new landscape be put? Agriculture, mountain biking, hiking, or kayaking? Or should it be rewilded and turned into a new habitat for wildlife?

National Controversy

Then again, the battle on the dams at Sélune may seem local but are, in fact, part of a broader national controversy fought over the embattled nature, the natural heritage of water mills, fishing wears and ancient property rights.

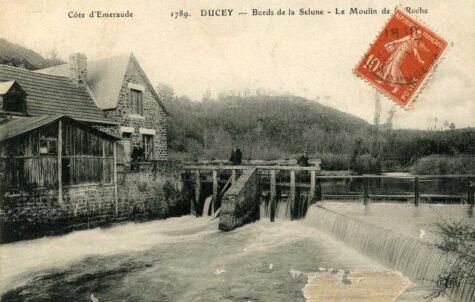

This story reaches back into Antiquity when watermills became a crucial technological innovation brought to the Roman provinces to be adopted widely in the successor-kingdoms. By the 7th century, water mills had been established in most of Western Europe, reaching into Ireland, and in Carolingian sources, references became legio. Two hundred fifty years later, Doomsday Book from 1086 counted more than 6500 in England. Most of these mills came with a weir creating dams, precious fish waters and a privileged status for the miller and his family. The importance of these visual and economically essential elements in the local landscapes is witnessed by the 100.000 mills and weirs built in the French landscape in the 18th century.

Around these millponds, a particular lifestyle and culture developed, part of which was local food featuring specialities such as bream, bass, carp, catfish, pike etc. In the 20th century, many of these mills were turned into riverside cafés which later metamorphosed into luxurious Michelin-starred hotels serving delicacies from the terroir. In short: they were fabricated as a treasured part of the heritagescape favoured by the privileged middle class. No wonder the Greens chose the free migration of salmon as one of their symbolic “fights”. Thus, a “Salmon Plan” was one of the first acts passed by the new French Ministry for Environment in 1971. Naturally, the dam owners took the bait, and battle commenced.

With the adoption of the European Water Framework Directive from 2000 into French law in 2004, the restoration of French Rivers to good ecological status became obligatory. This implied the restoration of “the free streamflow”, leading to a free and unhindered circulation of fish species and sediments. In practice, the removal of all old fish weirs – and the great dams at Sélune – impeding the migratory fish were the next logical step. Now, the fight was taken to another level, with a line drawn between on one hand the traditionalists with their local economic interests, and on the other hand the ecologists. The result was the formation of numerous factions and associations publishing reviews, monitoring laws, recruiting local people, and organising hearings, meetings and moratoriums.

At Sélune, these initiatives successfully drew out the dam demolition from 2009 to 2017. In the end, the lack of success led to the final shapeshifting of the anti-movement, now focusing on the “undemocratic and technocratic” decision-making process, which they believed undermined local interests and destroyed “la France profonde” with its heritage and landscapes. Vitriolising the debate, this new force occasionally even took to semi-violent harassment of local technicians and managers. Even regular violent attacks were orchestrated, leading to widespread fear of these opponents and their “attitudes”. This may have delayed and compromised the “achievement of environmental quality objectives”, wrote Barroud (2017).

Likely, this is the real reason why the ecological arguments for the demolition of the dams were subsumed by politicians beneath a version of a leisurely landscape filled with sports. And why the rewilded Sélune has been reduced to a late modern dream of a Parks & Recreation venue.

The Sélune River may once again flow freely. And yet, it has so far not turned into the fluid transient landscape nor the “natural backwater”, we may dream of. On the contrary, it remain a seasoned battleground for different stakeholders, upping the ante against the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law.

Karen Schousboe

SOURCES:

Biodiversité végétale précoce de cinq affluents de la Sélune dans la vallée renaturée de Vezin (Normandie)

By Charlotte Ravot, Didier Le Coeur, Simon Dufoir; Ivan Bernez.

In: Naturae (2021) Vol 26, pp.351-361.

Dam and reservoir removal projects: a mix of social‐ecological trends and cost‐cutting attitudes

By Michal Habel, Karl Mechkin, Krescencja Podgorska, Marius Saunes, Zygmunt Babiński, Sergey Chalov, Damian Absalon, Zbigniew Podgórski & Krystian Obolewski

In: Nature Scientific Reports (2020) 10:19210. Open Source.

Entre désir de nature et peur de l’abandon : quelles attentes paysagères après l’arasement des barrages hydroélectriques de la Sélune?

By Marie-Anne Germaine, Ludovic Drapier, Laurent Lespez, Marie-Jo Menozzi et Olivier Thomas

In: Projets de Paysage. Revue scientifique sur la conception et l’aménagement de l’espace (2019) vol 20.

New Sélune River (Normandy, France) margins following large dam removal: ecological restoration perspectives considering the successional vegetation dynamics of alluvial deposits

By C. Ravot, M. Laslier L. Muller L. Hubert-Moy , S. Dufour and L Bernez

I. S. Rivers (2018)

Removing Mill Weirs in France: The Structure and Dynamics of an Environmental Controversy

By Regis Barraud

In: Water-Alternatives (2017) Vol 10 No 3

The Failure of the Largest Project to Dismantle Hydroelectric Dams in Europe? (Sélune River, France, 2009-2017)

By Marie-Anne Germaine and Laurent Lespez

In: Water Alternatives (2017) Vol 10, no 3