What was the Middle Ages known for? Why was it called the Middle Ages? What characterised the Medieval World?

Historically, the idea of “The Middle Ages” was forged in the Renaissance to mark out the period between AD 500-1500, between Antiquity and (Pre)Modernity. As such, the history of the Middle Ages and the Medieval World should not be thought of as just any other period in our global history. Just as we have to acknowledge that the Chinese history of the Tang Dynasty between AD 618 – 907 touches very peripherally upon European history, we must think of “The Middle Ages” as a distinct period in the history of Europe, which only peripherally had an impact (if any) on the history of China in the said period.

Today, it has become fashionable to write histories of the Global Middle Ages. Here, we consider this a conceptual misunderstanding. It is, indeed, possible to write a global history about the period between AD 500-1500. But this should not be called a History of the Middle Ages.

Also to be noted: In modern parlance, “medieval” is often used to characterise something as “feudal” or even “barbaric”. Or denote a befuddled “Dark Age” between the more splendid and homogeneous cultures preceding and succeeding the period in between. Thus, this in-between-age was characterised by a relatively continuous and distinct presence of only very feeble unitarian political structures. Smaller and larger polities and cultures – sometimes quite diminutive – came and went and waxed and waned, creating the diverse and floating political landscape that forged the various European states. Some of these ultimately foundered (Burgundy) while others flourished (Portugal). Surrounding this pandemonium, the Catholic Church, the Byzantines to the East and the Muslim World south of the Meditteranean may have appeared as three “imperial” institutions constituting opposing centres. The truth is, the constant fragmentation (infighting) in the peripheries of these three major players was the constant factor. Occasionally, seats of power crumbled or rose to new strength. However, the continuous raiding, war-faring, conquests and dissolution set the predominant tone.

Traditionally, the history of the interplay between these polities is divided into three major periods:

- The Early Middle Ages AD 500 – 950

- The High Middle Ages AD 950 – 1348

- The Late Middle Ages AD 1348 – 1500

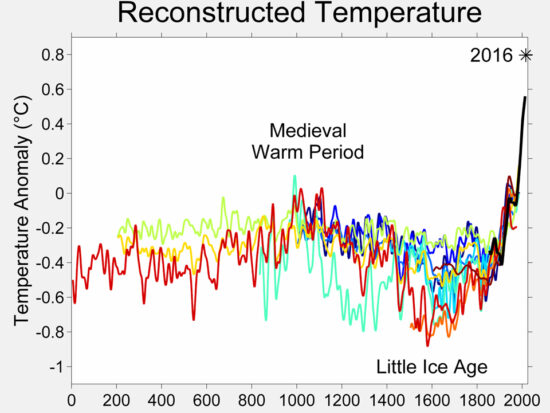

These shifts were framed by notable climatic and demographic shifts, termed:

- LALIA – The Late Antique Little Ice Age – AD 536 – 700, and the Justinian Plague – AD 541– 700

- The Medieval Optimum – ca. AD 950 – 1300

- Black Death – AD 1348 – 1700 accompanied by the Spörer Minimum ca. AD 1460 – 1560, ending in the Little Ice Age – ca. AD 1550 –1700

THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES AD 500 – 950

The end of the Roman Empire in the West

At the dawn of the Middle Ages, a perfect storm seemed to rise. Climate changes set an end to the so-called Roman Optimum, a period with warm weather. After AD 200, the weather became more volatile. Likely, this change contributed to the major migrations of the Goths from the North and the Huns from the east in the third and fourth centuries. In the 370s, these two peoples (tribes, nations, bands of brothers) together with their allies collided to the North of the Danube. These events led to a massive migration of Goths across the Danube in AD 376, ending in the annihilation of a huge Roman army in AD 382. Following these events, the Gothic leader, Alaric, invaded Italy. This invasion ended in the sack of Rome in AD 410.

Afterwards, his successors established the first barbaric kingdom inside Gaul (the Visigothic Kingdom in Toulouse), while another group – the Sueves – settled in Western Iberia. Meanwhile, the Western Roman Empire bled economically to death, trying to pay Germanic mercenaries to stop the Hunnic invasions.

Conventionally, the period between AD 300-500 is termed Late Antiquity to indicate the period as a transitional interim leading to the advent of the Middle Ages. However, as with any transitional phase, the dates are nothing but valuable indicators. The extent to which Roman civic culture continued to set its mark on the new Medieval Europe has been continuously debated. Nevertheless, we may conclude that several barbaric successor kingdoms were established between AD 500-600, following a climatic collapse in the North and the ravages of the Justinian Plague. Out of these grew the political and linguistic diversity of present-day Europe – a Europe of nations and nation-states.

Jews, Christians and Muslims – three kindred world religions in the Middle Ages

Classical Greco-Roman religion was centred on a pantheon of civic gods celebrated in the city’s forum coupled with the household deities of the family, venerated in the lararium in the atrium of their house or villa. Late Antiquity, however, came to nourish a new, more philosophical and religious ferment inspired by Eastern thinkers and pantheons. One ingredient was Neoplatonism, which fostered an inclination to believe in one divine power. Other options were the Jewish and Christian monotheistic faiths. After AD 70 and the destruction of Jerusalem, the Jews dispersed across the Mediterranean. During the same centuries, the Christians set their mark up to and after AD 311, just as the military cult of Mithras presented an option to the army. Later, after AD 632, this Judeo-Christian tradition fostered Islam. All three traditions operate with the idea of one God (and his representative on earth) to whom people are ultimately answerable. Based on this idea, these three religions wielded a theocratic belief system, in which office-holders got established according to the “nearness” to God

- either as descendants of the “founding fathers” (Abraham, Isaac or Jacob)

- or designated as vicarious heirs (the Patriarchs and after AD 426, the Rabbis, the Popes and Bishops, or the Caliphs) of the prophets (Moses, John, Paul and Peter or Muhammad)

- or appointed as their heirs by the representatives of these kings.

During the Middle Ages, these theocracies competed for power with secular autocracies such as those wielded by warlords and their retinues, as well as urban patriciates.

The poor and the powerful in the Middle Ages

Thus, during the Middle Ages, the theocracy sported by the religious institutions constantly entered into a rivalry with the competitive secular worldview of the relevant powers, whether kingdoms, warlords, or the more or less fragile justiciary institutions (public courts, guilds, things, moots and parliaments). In the early Middle Ages and until the 13th century, kings, kinglets, and warlords were the primary political actors acting together with their private armies and aristocratic retinues. At the same time, the idea of civil servants was only kept spuriously alive in a religious setting.

At any time, at least 90% lived as peasants – whether as slaves, serfs, craftsmen, or small landholders. Lordship would be exercised in different ways according to history, tradition, natural resources and available technologies.

During the Late Antiquity, the Roman villa continued to dominate the landscape with its slave economy. Later, manorialism, also called the manorial or seignorial system, was based on the extraction of surplus from peasants farming their own land as well as that of the demesne. The basic unit was the castle or manor possessed as either personal property (heritage) or fief. While the former was handed down as part of a dynastic holding, the latter was held under vassalage. Ultimately, this part of a lord’s demesne might revert to its owner – the king or an overlord.

Dependent on the case, the lord of the manor enjoyed a variety of rights to corvee, taxes, income from monopolies, jurisdictional fees and other petty income from the landed serfs.

Very few people lived in cities and earned their income from plying crafts or trade. Seasonal markets and fairs were essential places for the distribution of goods.

The Carolingians and their Empire

After the final collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century and in the shadow of the climatic and demographic crises of the 6th and 7th centuries, the new successor kingdoms slowly established a new equilibrium. Major players were the Franks, the Visigoths, and the Lombards encircled by petty (often non-Christian) kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England, Scandinavia, Saxony and further east (of the Elbe); and to the south in Iberia (after AD 711), the Muslim caliphate. During the 8th century, however, the Carolingians established a powerful ruling dynasty with a centre at Aachen and a dominion covering most parts of present-day France, Germany and Italy (north of Rome).

In AD 800, a power vacuum in Byzantium even opened up for the symbolic re-appropriation of the title of the emperor by a Western warlord, Charlemagne. As the supreme overlord, he presided over a massive effort to rule – and correct – the life and circumstances of his people according to the Gospel and the Church. Arguably, this was the first major experiment in rebuilding the Roman Empire in the West.

THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES AD 950 – 1348

The turn of the first millennium

During the 9th century, however, this empire imploded. The political centre of gravitas moved to present-day Germany, where several new dynasties – the Ottonians, the Salians, and the Hohenstaufens (ca. AD 919 –1254) ruled as both kings and Holy Roman Emperors.

At the beginning of this period, medieval Europe was once again besieged by people from the North and the East – the Vikings, the Magyars and the Slavs. While the rulers of present-day Germany succeeded in holding the fort, the Vikings gained significant footholds in Ireland, the Danelaw in England and Normandy in France. To the east, the Vikings – the Rus’ even succeeded in creating the most extensive European kingdom at the end of the 10th century.

Also, in this period, the three kingdoms in Scandinavia were established following Christianity’s formal adoption. For a short while, even Anglo-Saxon England was conquered by the Danes, later to be superseded by the Normans. At the same time, the Normans also invaded and settled in Southern Italy and Sicily. To the east, the Magyars established a kingdom in AD 1001, while the Slavs can date their polity, Poland, to AD 966. Most of Iberia, though, continued to be ruled by Muslims until after the conquest of Toledo in 1086. During this period, the foundation was laid for most of the modern European States, which are still in existence today.

Accelerating growth and division of labour

Between AD 950 and 1250, medieval Europe entered a new climatic optimum characterised by warm and propitious weather. These favourable conditions were accompanied by a number of demographic, economic, social, religious and cultural changes and the accelerated division of labour. Numerous explanations have been offered as to why this growth occurred – technological, religious, or ideological. Suffice it to say, changes in all these parameters took place, leading to increased food production, the castellation of the countryside, an acceleration of trade, and general urbanisation.

These changes were accompanied by a widespread decentralisation of power, leading to the establishment of a more widespread form of lordship based on feudal-vassalic ties. Simultaneously, new juridical instruments were instituted to formalise the proper relations between kings, magnates, lords, bishops, priests, peasants and burghers. This development involved establishing English Common Law in England, while Roman Law elsewhere came to influence the customary laws.

Gregorian reforms

During the same period, a significant rethinking of the theology and organisation of the medieval Catholic Church took place. In terms of theology, the reforms reinvigorated the simple and austere living of the early Benedictines, focusing on manual labour and self-sufficiency. Later, spiritual growth was fostered by the Cistercians, and even later, the friars – the Franciscans and Dominicans. In the wider Church, the moral leadership of priests became of utmost importance. Simony, priestly marriages, and lustful lives were to be uprooted.

In terms of the Church, the self-government of the “mystical body of Christ” came to be the uppermost political concern in the 11th and 12th centuries. These ideas led to several spectacular conflicts between popes, bishops, kings, and emperors, which became known as the struggle between Church and State.

One primary objective of these reforms was to quench the rampant violence, which followed in the footsteps of the feudalised society. At first, the peace movement known as “The peace of God” was established to set up the rules for engagement. This endeavour was followed by the development of the concept of chivalry and the launch of the crusading movement.

The New Man and the New King

Parallel to these new ways of thinking about the role of the Church in broader society, a new form of philosophical thinking, scholasticism, came into being. Again, a major impetus came from rediscovering the works of Aristotle and other mathematical and astronomical works, which had over-wintered in the Islamic world.

Medieval scholasticism emphasised reasoning and logical thinking to resolve contradictions more as a learning method than an actual philosophy or theology. The principal example of such a debate was on the nature of the transubstantiation of the Eucharist. This set of questions continued to be debated until 1215 when the delegates in the Fourth Council of the Lateran decided on the question (for now).

Scholastic or scholar means schoolman. Thus new schools, the first universities, accompanied the development of scholasticism, first in Bologna (AD 1088) and soon after in Paris (ca. 1150) and in Oxford (1167). The importance of these universities as secular institutions was considerable as the Law became one of the significant new fields for study. Central here was the rediscovery of the 6th-century Corpus Iuris Civilis at Pisa, which was taught at Bologna from 1088. The idea of a new man was forged in this crucible – rational and competent, given over to contracts, agreements, deliberations and justice. This “new man” was destined to work in the new and growing cities.

Following the scholarly discovery of this collection of Roman laws, a fashion developed for gathering and writing down or even composing new rules of laws. The 12th and 13th centuries witnessed the publication of several significant compilations of laws. We might mention the Sachsenspiegel of Eike von Repgow (Germany, c. 1200 – 1230), the Siete Partidas (Spain, c. 1256 – 1265), Jyske Lov (Denmark 1244). Other work was published as tracts, for instance, that of Henry de Bracton, Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus Anglie from c. 1235 or John of Salisbury and his Policraticus, written between 1154 and 59. Later, Marsilius of Padua and Bartoldus of Saxoferrato took up the mantle of political writings.

At the centre of these writings was the question of how to legitimise a king. Formerly, kings had been legitimised by their elections, followed by ritualised anointings and coronations. Now the sanctified oil of the Church became reserved for the clergy and other religious persons (a substitute was developed for coronations). Instead, kings came to be legitimised dynastically – as heirs according to laws of inheritance. Alternatively, they became recognised as givers of laws while enacting their role as supreme judges. Also, where kings had formerly signalled their power through rituals, wealth and magnificence became steadily more important.

Urbanisation, literacy and double-entry bookkeeping

In Late Antiquity, towns had continued to function as centres for mints, tax-collection, judicial institutions, civic culture and learning. During the 5th and 6th centuries, most cities were reduced to smaller walled centres holding bishops, seats, and cathedrals. It took until the turn of the first Millennium to see a substantive growth of these cities and towns. Mostly, this development was set in motion by the new and more independent bishops. However, guilds and the new merchants were also active in creating these new and vigorous marketplaces.

In need of a juridical system of law and order, the cities grew up around the old idea of a” res publica”, a common order of public matters. Gradually, some cities gathered so much power that they organised themselves in leagues (Northern Germany) and even city-states (Italy).

With their stress on literacy and (later in the 13th century) double bookkeeping, the new schools and universities also played a significant role. Ambulating tradesmen turned into proper merchants. A precondition was the new shipbuilding techniques, which vastly improved the possibilities of moving goods around Europe.

THE LATE MIDDLE AGES, AD 1348 – 1500

Crisis and contraction

At the end of the 13th century, growth stalled. Once again, climate changes set the process in motion. Periods of droughts and rainy weather alternated, creating the preconditions for periods of hunger, pestilence and a general economic downturn. The final coup was the Black Death, which hit Europe after 1348, killing at least 40-50% of the population. This massive depopulation caused widespread economic inflation of salaries and deflation concerning luxury articles. One way of coping with the lack of manpower in the countryside was the marked shift from intensive to an extensive rural economy. Also, the dispersal of all the orphaned wealth floating around in the deserted villages created what must have felt like a bonanza for the survivors.

This crisis unfolded in the shadow of a European struggle for supremacy between the French and English kings, with parallel wars fought in Scandinavia, between the Hanseatic faction and the Danish Kingdom, warring between the Poles, the Czechs and the Hungarians, conflicts between Italian city-states, and finally the progressive re-conquest of the Muslim petty kings by the Castillian and Aragonian crowns.

One may well ask how these armies were manned in view of the lack of manpower that followed in the footsteps of the plague? One answer to this question was the deployment of new military strategies and technologies such as guns, caravels, and longbows.

The retreat of the church and the spiritual renewal

The medieval Church gave ground to its hierocratic aspirations in the same period by finally transforming the popes into worldly princes. No longer driven by universalistic pretensions, the Church lost its moral and spiritual leadership. From 1309 to 1376, the Popes lived in the “Babylonian Captivity” in Avignon, while poor local priests or the Franciscans provided spiritual sustenance; even lay movements like the Beguines and later the Devotio Moderna came to solace the souls in the 15th century. No longer was scholastic thinking or teaching promulgated; rather, the inner spiritual life of a person became important. The gradual shift towards lay involvement accompanied this shift. A late medieval person of substance owned a personal prayer book and perhaps even a translation of the Holy Scripture into the vernacular.

The later Middle Ages witnessed the transformation of rational thinking persons into sensitive and emotional beings complete with inner selves and ensconced in their families and domestic setting. This new spiritual sensibility eventually led to the Reformation in the 16th century, while the shift in religious language drove the formation of nationstates to fulfilment in the 17th century.

The Gutenberg Galaxy

At the end of the Middle Ages, a new technology, the invention of the printing press, came to define the moment. Famously termed the Gutenberg Galaxy by Marshall McLuhan, movable types forged a new world where texts might be reproduced accurately, swiftly and ready to be consumed by everyone. Suddenly, a mighty lord or a lofty priest no longer had the full power to filter the world of the peasant. Widespread literacy followed, creating a vast space of possibilities – including overseas travels and trade on a global scale. The Renaissance – and later, the Enlightenment and Modernity – had arrived..

FEATURED PHOTO:

Anonyme, Livre de l’information des princes. Translated by Jean Golein, France, Rouen, v. 1450. BnF fr. 126, fol 7r. Source Gallica

HANDBOOKS AND INTRODUCTIONS: