Keeping geese is complicated and labour-intensive. This created an intricate network between people in villages, on manors and in towns.

The goose is a complicated animal to raise. First of all it mates for life, which means that a gander will only serve 1 to 4 geese at the most. This means that feeding a flock of geese will include feeding a number of ganders, otherwise (in terms of eggs: barren). Secondly the animal feeds on greens on pastures and later the stubble of the harvested field; as opposed to chickens, which are rather omnivorous. Geese – because they feed on greenery – need to be herded properly. Geese are labour intensive.

However, in a medieval context the goose provided a number of significant and important products: fat and tasty food, feathers for writing materials or fletching arrows, down for the filling of blankets, pillows and clothes, and wings used for brooms. It appears to have been worth it.

The life cycle

First of all it is important to note that the goose is a typical part of the agricultural production in villages located on the plains and lowlands of Europe. Settlements in forests cannot as easily provide for them in late autumn (less stubble). This is a lowland creature, which fills a niche on the fringes of the peasant economy.

The goose lays its eggs in March and April – from three to twelve eggs and begins to brood when the last egg is laid. They often lay more eggs than they can brood, hence the practice of farming goose-eggs out to hens. The goslings hatch after 27 – 29 days. One group of adult geese (a gander plus three females) on an average farm might thus produce up between 20 and 36 goslings. These would be taken to pasture on the common land of the village together with those of the neighbours. The village would typically hire a common goose herd to bring them out to pasture each morning. From Germany we know that specific shelters were built for housing the geese by night.

Around the age of 12 -16 weeks the goslings might be culled for the first time bringing so-called green geese to the market. At this point they had come into full feather and the wings were usable for pen-production as well as brooms. Another option, though, was to wait in order to fatten the geese on the stubble in the autumn. This would also enrich the potential income by allowing the geese to be plucked for downs and feathers. It is possible to pluck the animals at least twice a year. But again, this is typically a labour-intensive affair, suitable for being embarked upon by families with lots of children; or manors with plenty of labour craft available.

Raising geese and profiting from them was thus a typical side-activity of a household equipped with a labour-reserve (children) and a need for ready money. This is well known from peasant accounts from the Early Modern period and seems to have been the case in the Middle Ages as well, judging by the evidence collected from the survey of large medieval manorial accounts and archaeological excavations carried out in Britain by Slavin.

An economic system

The point here is that we get glimpses of geese and presumably products from geese traded up and down the agricultural system exploiting a peripheral niche: pastures on roadsides or in wet meadows, where cattle is to heavy to graze. The use of stubble in the late autumn is another bonus.

We know from later times that small landholders might produce the goslings, which were then sold or rented out to large-scale producers, wealthy peasants or local lords (with rights to pasture them out on commons or on the land of the manor). At some point (after having been plucked) they would either be walked to the market, or they would be killed and consumed.

At the other end of the social landscape we know that manorial economies following the late medieval crisis in the 14th century leased their geese-flocks out to peasants for substantial sums.

Much has been written about the practice of “shooing” the geese before walking to the market, but it is in fact probable that villagers would practice the slaughter at home, cutting off the breasts for salting or pickling. These would then be sold in the nearby town, while the rest – the carcass – would be used for cooking soup. The blood would in a Scandinavian context be used for a special dish called “Black Soup”. Traditionally this would be soup into which would be mixed the fresh blood from the slaughtered goose (or pig).

Archaeological Evidence

The reason, why this practice of selling the choice meat in towns, while reserving the carcasses for home-consumption may have been prevalent in an English medieval context can be found in the archaeological evidence, which has demonstrated that there is little evidence for the bones of green geese in e.g. Winchester between the 10th and the 15th and 16th centuries. (Serjeantson, 2001, p.49). Another, less, likely explanation is that geese were not consumed in the medieval towns until late in the autumn, at St. Martin’s feast and at Christmas. However, this was the time for both slaughtering larger animals and fasting, thus rendering the goose as a staple less attractive. The quality of the goslings was that they were readily available to eat in July and August, months otherwise barren of meat. It is probably significant that the accounts of Dame Alice de Bryene demonstrate that the peak month for eating geese in her 15th century household was August.

Perhaps the tradition of eating roast goose at St. Martin’s day (Martinmas) stemmed from the need to do a final culling of the geese before winter; but at a time, when it was obvious how many geese had to be overwintered in order to overwinter a reproducible flock.

Registers of toll from medieval towns may in the future shed further light on the intricate economic interplay between the different stakeholders in the medieval goose.

Sources:

Alternate fortunes? The role of domestic ducks and geese from Roman to Medieval times in Britain.

By Umberto Albarella

In: Documenta Archaeolobiologiae III. Feathers, Grit and Symbolism. 2005. Ed. by G. Groupe and J. Peters, pp. 249 -58

Goose Management and rearing in Late Medieval Eastern England, c. 1250 -1400.

By Philip Slavin

In: Agricultural History Review, 2010, Vol. 58, No. 1, pp. 1 – 29

Chicken Husbandry in Late-Medieval Eastern England: c. 1250 -1400

By Philip Slavin

In: Anthropozoologica 2009, Vol 44. No. 2, pp. 35 – 56

Goose husbandry in medieval England, and the problem of ageing goose bones

By Dale Serjeantson

In: Acta Zoologica cracoviensia 2001, 45, pp.39 -54

READ MORE:

Alternative Agriculture: A History

From the Black Death to the Present Day

By Joan Thirsk

Oxford University Press 1997

ISBN: 978-0-19-820662-0

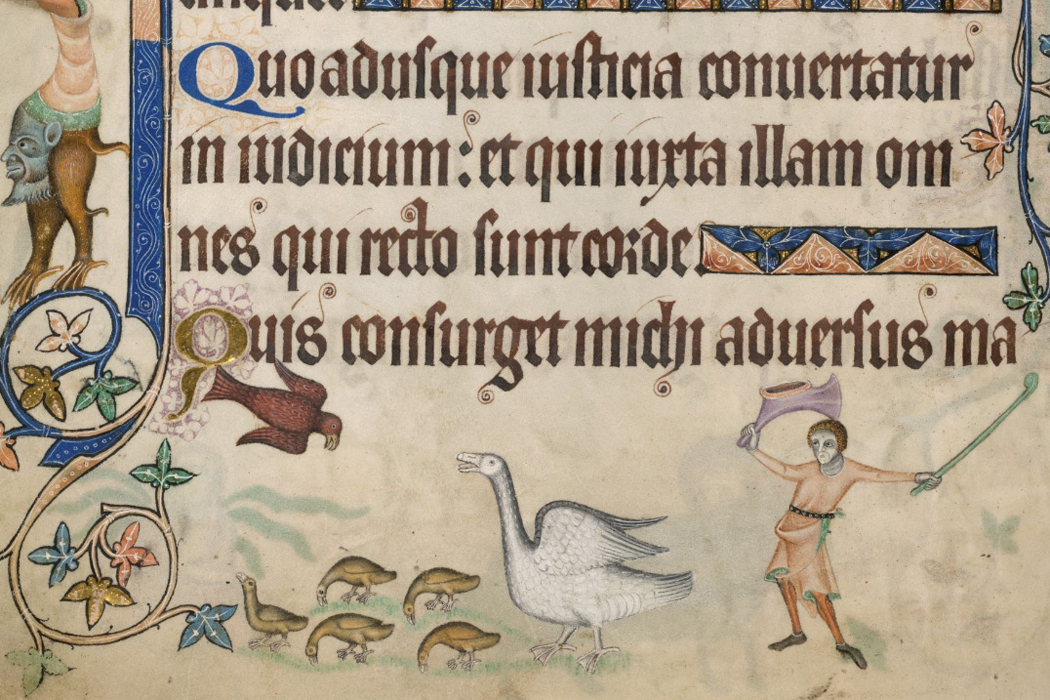

FEATURED PHOTO:

Luttrell Psalter: Herding Geese and fighting off hawkish predator. Add MS 42130, fol 169v. © British Library