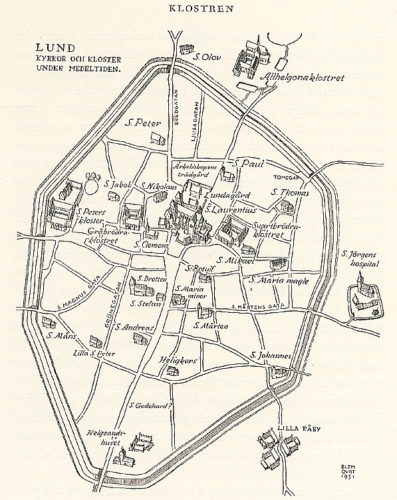

Lund is a city in the province of Scania. Believed to have been founded in AD 990 it soon became a major Christian centre. In 1103 it was designated as the see of the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Scandinavia. It still retains its medieval outlook.

The origins of the medieval city of Lund are unclear. Until recently, it was believed to have been founded by his son Cnutr the Great of Denmark at the turn of the millennium. However, recent archaeological discoveries suggest the first settlements can be dated to ca. 990, the reign of Sweyn Forkbeard. Possibly settlers were relocated from the early medieval pagan centre, Uppåkra, which was located at a distance of app. five km; the shore of Øresund lies ten km. to the west. In between Uppåkra and Lund was the ancient meeting place for the regional “thing” and it is believed this may have contributed to the location of the future city.

Uppåkra lies on the plain located between the so-called “Rommelås” and the sea covering more than 40 hectares of land and with a continuous settlement reaching back from c. AD 1000 to c. 100 BC. Well-known for its series of ceremonial or cultic building erected on the same spot from c. AD 500 to AD 1000 it also encompassed rich market facilities and specialised crafts- and workshops. Through Uppåkra runs a road, which leads inland across Høje Å. Some km north of the ford this road crosses another, which leads from east to west. Here at this junction was open outlying land crisscrossed by ridges, and streams.

Located on a hill and above a damp and swampy area, this new location seems to have provided ample opportunities for an ecclesiastical and administrative centre established to control communication and tax collection. Probably conducive to the location was also the fact that the new town was built on royal land. The Danish kingdom was a relatively new regional power established in the end of the 10th century. Lund was the direct result of the need for this new power to establish a competing centre with the old Uppåkra.

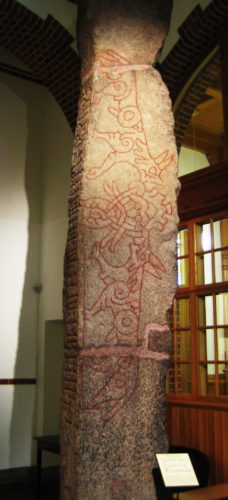

Politically, ideologically, and culturally an ecclesiastical complex consisting of a fortified manor with a nearby church dominated Lund around AD 1000, obviously superseding nearby Uppåkra. Later historians have explored the significance of the remains of elite manors elsewhere in the burgeoning town, but it seems evident that Lund primarily was a royal settlement on par with that of Roskilde from the same time (which also represents a discontinuity of the former pagan centre at Lejre). That local nobles continued to play a significant role is witnessed by the large Runic Stone called the Lundagårds-stone found immediately north of the medieval city. The inscription reads: “Þorgísl, son of Ásgeirr Bjôrn’s son, raised these stones in memory of both of his brothers, Ólafr and Óttarr, good landholders” . (“Landholders” meaning local magnates). The impressive four meter high stone, dated to c. AD 1000 can be seen in the entrance hall of the University Library in Lund. It has an impressive decoration showing two wolves attacking a man with a lion’s mask.

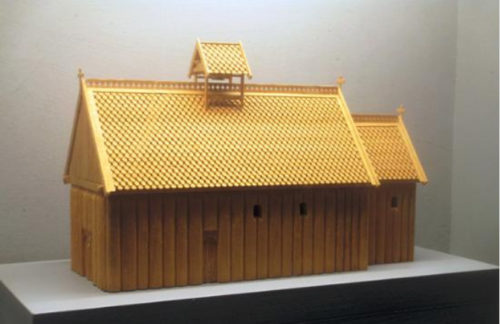

The earliest remains of Lund is a Christian burial ground dated c. AD 990. This was located c. 30 – 40 meters west of the earliest wooden stave-church found in the city located in the south-west rectangle. This may be the church, which the Roskilde Chronicle tells us Sweyn Forkbeard built in Scania and which has been dendrochronologically dated to around AD 990. A curiosity is that this church seems to have been partly built on top of the cemetery. It has been suggested that the Christian graveyard was in fact constructed at a somewhat earlier point and intended to cater for a growing Christian population from Uppåkra. A bit later the stave-church was built on top of some of the graves; finally, in the beginning of the 11th century the stave church was torn down and rebuilt in stone. This is known as the later St. Salvator (Drottens Kyrka), the ruins of this can be visited. Next to visitors will find a small museum, which tells the story of the earliest City of Lund.

In the 80s the archaeologist, Anders Andrén, concluded that the city in all likelihood had been founded as an administrative centre intended to serve the alliance between the newly established church and the king. This centre was used to house a mint as well as hoard royal taxes levied on the three nearest hundreds. At this point the meieval city of Lund seems to have had no more than two churches: the one mentioned above, and (probably) a stave forerunner(s) of St. Laurentius, the future cathedral.

Another explanation is the need for Viking magnates to have ample access to forests supplying wood for the constant refitting of old ships and the building of new. Some archaeologists believe the gradual royal conquest of the eastern part of Denmark reflects the thinning out of the forests in Jutland.

We know that the early buildings in Lund were constructed of wood in the fashion of the so-called Trelleborg houses. But even later, when new building techniques came to dominate, wood continued to be used generously. It was not until mid 12th century oak turned into a dwindling resource forcing the use of bricks for representative house and stone-work for ecclesiastical buildings.

The Royal Manor – Lundagård

It is believed a royal manor was located north of the east-west road and west of the later cathedral. Remains of an early stone-house (a palace or hall?) have been found. This was obviously older than the first cathedral from the beginning of the 12th century. In another location, a tympanon was discovered depicting a rider on a horse carrying a falcon, much like the earliest Danish royal seal (Saint Cnut’s). Might this belong to this stone-house? In all likelihood, the king had access from here to the west end of the two churches, St. Salvator to the south and St. Laurentius to the East. Nearby was perhaps the royal mint. Behind what was later to become the cathedral, the Episcopal seat was located. The royal manor was first donated to the bishop in 1375 – 87. Until that time the city was both royal and ecclesiastical.

With the royal and episcopal centre nesting in the north, the new town was organised with plots running along each side of the “large square” of the oblong street, called “Stora Torget”. These plots were equal in size (app. 2000 – 2500 m2) and covered with buildings looking much like the large Viking farms excavated elsewhere. Buildings were constructed as halls in the Trelleborg Type.

After AD 1050

Soon after 1050 the new town began to change. Around 1050, five new churches were built with an additional five constructed in the next decades.

At the same time the fabric of the city became gradually more dense, reflecting the changing status of the place from a royal centre to a proper town. Perhaps the city accommodated a population of 3-4000 around 1100. For instance a plot in Gyllenkrok has been archaeologically excavated. Originally a large Viking Farm/manor it was soon divided into nine different plots during the second half of the 11th century. It is estimated that the original 65 – 80 Viking farms ended up as 600 – 700 medieval house plots. With 10 – 15 people on the 11th century farms the town housed max 1200 persons at that time.

During this period the town was also fitted with a fortification and a ditch encircling the 84 hectares city. 15% is still preserved and may be seen in the present city park. It is believed that the wall was topped with a wooden palisade. It is from this period the present network of streets should be dated.

After AD 1200

Later, at the end of the Middle Ages, Lund mustered 22 churches servicing the city as well as the surrounding countryside at a radius of up to five km from the centre. At that time the centre of Lund had turned into a commercial city with perhaps 5- 7000 inhabitants. Lund was no longer just an administrative centre, but a vibrant commercial city. Now the buildings looked like the typical late medieval town houses, built of bricks, with gables fronting the streets and side-buildings reaching to the back where gardens were located.

Most of the building fabric was half-timbered, but we know from written sources that app 40 stone houses could be found in the city of Lund at the end of the middle ages. Most of these were owned by church institutions and served as homes for deans, clerks and other administrative personal involved in the running of the archbishopric. Others belonged to the nobles ruling the region.

Stone Houses in Lund

Walking through Lund today is much like taking a trip down a medieval lane. As said above: streets and alleys run much as they did in the 13th century. Another feature is the preserved medieval houses made of brick.

The best preserved stone-house is called the House of Krognos. It belonged to the very rich noble clan named Krognos and was apparently build around c. 1300. It probably served as the town residence for the Krognos family, who owned the plot until 1619. The name reflects the large crooked noses of these magnates, who owned extensive land and castles across Scania.

Another medieval residence, which can be visited, is located in Kulturen – the local open-air museum (which also holds a fine medieval and regional exhibition). This residence was probably also build in the 14th century. Much restored in the 15th, it was reconstructed in the beginning of the 20th century, when it was moved to the museum.

A third important building is the Liberi, constructed around 1400 and used as the library of the cathedral. This is the only medieval building left of the vast building complex, which used to surround the Cathedral and the Bishop’s seat – the former royal residence.

Finally, Stäket, should be mentioned. Although fitted with a distinct “medieval “ look, the two buildings were built in the 16th century as part of a noble house on a plot between Södergatan and Grönegatan. This is now a restaurant, which serves traditional food from Scania.

Churches

The earliest stave churches constructed of wood have left no remains apart from archaeological traces. However, the ruins of St. Salvator (St. Drotten) can be visited. This church measured 51.5 m and was 14 m. wide. The choir measured 10 x 10 m. and ended in a half circular apsis. Beneath the chancel a grave-chamber was found measuring 4.9 x 6.3 m and with a height around 1.7 m. Another, larger, grave-chamber was found in the nave. Both were empty, but it has been speculated that Sweyn Forkbeard was moved here after his initial burial in the wooden forerunner of the church. Later, he was removed to Roskilde, the future royal centre in the Danish Kingdom. But all this is somewhat speculative.

From the next phase (mid 11th century) a series of wooden stave-churches have been documented archaeologically. It has been speculated that these churches were initially private chapels connected with the large Viking farms, which were still dominant in the topography. One Runic stone found in the city tells the story: “Tóki had the church made and …” (Now walled in at the bishop’s house in Copenhagen).

The first bishop in Lund was raised at the court of Cnutr the Great in England where he was keeper of the treasury. Sometime around 1035 he was appointed as Bishop in the Orkneys. He may also have been bishop in Iceland for a short period. However, in 1060/61 the Danish King appointed Henry bishop of Lund as part of the king’s plans to get a separate archbishopric established in Scandinavia. However, in 1066 Henry died and these plans came to nothing. Henry of Lund had been a suffragan to the Archbishop of Canterbury; now his post was taken over by Egino, who had been appointed bishop of nearby Dalby by the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen. King Sweyn obviously had to step-dance between the German Emperor and the Pope, who wished to secure the friendship and the troops of the Danish king, in his on-going feud with the Emperor, Henry IV, and his lords, the German bishops. At this point, the emperor seems to have had the upper hand and the intrigues designed to establish a separate Scandinavian Archbishopric did not meet with success until 1103.

Whether or not these two early bishops used the church of St. Salvator as their Cathedral or whether an early forerunner for St. Laurentius filled this function has been debated.

After the Reformation, the many churches in Lund were torn down. Apart from the Cathedral (see below) only the Church of St. Peter still stands. This church belonged to one of the religious institutions located outside the city walls, the priory of St. Peter. Originally a convent housing Benedictine nuns it was founded around 1145by Archbishop Eskil. Around 1300 the church was rebuilt in brick and in a Gothic style. After the reformation, the priory itself was torn down, but the church was kept standing. It still serves a local congregation . The church is well worth a visit due to its charming late-medieval retable.

The Cathedral – St. Laurentius

This is one of the finest Romanesque buildings in Scandinavia. A predecessor, which was excavated 75 years ago was inspired by Anglo-Saxon designs, and presumably constructed in the early years of Sven Estridsen’s reign, ca. 1050. However, in 1080 the construction of the present building was initiated. It is reasonable to believe that the crypt, the nave and part of the towers were standing around 1100.

The crypt is the oldest part. This was dedicated to St. John the Baptist and consecrated in 1123. In the crypt was a spring, which is believed to have been used as a baptismal font. Even though the room is now filled with the massive tomb of the last Catholic Archbishop, Birger Gunnersen and the spring, which has been fitted with a late medieval encasement or well head made of square sandstone reliefs by Adam van Düren, the room still oozes of the stark message send by an early missionary church operating in a world, which was only recently Christianised; especially, when the Cathedral refrains from using the crypt as an exhibition space for modern art!.

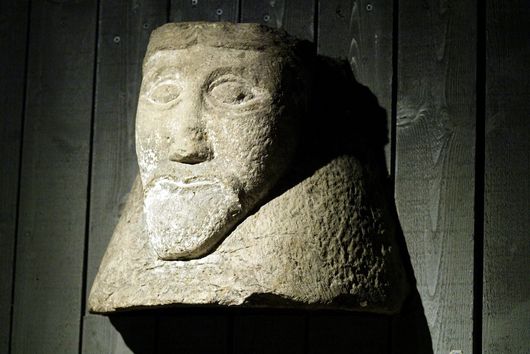

Significant are the two enigmatic stone pillars grabbed by two figures. Legend has it they represent the giant troll, Finn, and his wife and child. According to the local version of this widespread myth, a monk, who had undertaken to build the church, secured the help of a local giant. However, before the church was finished the monk had to guess the name of the troll. If not, the monk had to turn over his eyes. As it happens, the monk heard the wife of the troll singing a lullaby to her child near their home in the wilderness (at Romeleklint) behind the new city. Your name is Finn, the monk cried out just before finishing the church. However, the giant turned vivid with anger and ran into the crypt to dismantle the fabric. Unfortunately, he was immediately turned into stone as was his wife and child.

The pillars – which are unique in European art history – were regrettably disfigured (“cut clear”) during a royal visit in the end of the 18th century – and it is not known how they precisely looked like.

However, 65 km north in the village of Gråmanstorp, a stone relief can be found on the baptismal font, which shows the same motive as one of the columns in the Cathedral. However, here, there is no doubt. The figure depicts Christ on the third day carrying Adam out of Hell beneath the watchful eyes of the heavenly hosts. The church at Gråmanstorp is believed to have been built around 1160 by the stone-cutters and masons from Lund after the Cathedral had been finished.

In 1967 Göran Axel-Nielsson argued that the figures were in fact depicting Christ at the Pillar building up the new church as depicted in a manuscript holding the Annales Colbazenses. The other pillar, which folklore tells us is the wife and child of Finn is in all likelihood Christ carrying Adam from Hell.

With this explanation in hand he was able to argue that the architecture of the crypt in all likelihood was intended as a compact lesson in the basic tenets of the Christian faith – the resurrection, the redemption of the “pagan ancestors” through prayers of intercession leading to baptism and rebirth. What we have now are fragments of what was in all likelihood a pictorial program constructed around the baptistery and the altar, both cleared out by Adam van Düren at the behest of Birger Gunnersen, when he chose his last resting place at the exact place where the altar was constructed in 1123.

The columns holding up the 41 vaults in the crypt are reminiscent of the Anglo-Norman Cathedral in Durham and the architecture in the crypt was obviously reflecting the close political and ecclesiastical ties between the city of Lund and England, which were forged in the reign of King Cnutr the Great and which to some extent were upheld in the following period.

The Upper Church

The Cathedral itself was consecrated 22 years later, in 1145. The church was early on covered in sandstone from Höor and fitted with marvelous reliefs – first in an Anglo-Norman style. Later Italian and German stonecutters and artists set their mark. Some of the early stone-reliefs were never completed and witness to this shift in taste. Some of the more “modern” artists obviously spilled over from Mainz and Speyer and helped to make the upper church look like these magnificent cathedrals. Heavily restored in the 19th century visitors will nevertheless have to struggle to imagine the medieval cathedral. Archaeological excavations tell us that the church was extensively decorated with murals and that the original flat roof was first vaulted in the 13th century. Between the nave and the choir a 5 m high wall served to close off the choir and chancel from the nave.

During the 19th century restoration of the cathedral two new towers were built while the cluttered post-reformation interior was “renewed”; that is brought back to its presumed early medieval outlook. Thus, the walls and screens were removed and instead an impressive set of stairs was installed to mark off the chancel from the transept and the nave. Here in the choir is the retable from 1398. The choir stalls have been reinstalled after their initial removal in the beginning of the 20th century. During vesper mass is celebrated in the choir. However, during Sunday service a modern altar is used, which has been placed at the foot of the stairs in order to secure a more “welcoming atmosphere”.

In 1925 – 27 the apsis was decorated by a mosaic by the Danish Artist, Joakim Skovsgaard and is considered one of his masterpieces. This reminds us of the preoccupation of the artist with early Roman mosaics.

Luckily the portals and the exterior of the apsis were kept intact, which means we may still enjoy the magnificent Romanesque sculptures and tympanons.

Finally, worth seeing is the work of one of the prominent artists active in the beginning of the 16th century was Adam van Düren (c. 1487 – c. 1532). He was active during the renovation of the Cathedral in Linköping and he probably also worked as an architect of Glimmingehus. In 1513 – 27 he renovated the crypt in the Cathedral in Lund installing the famous wellhead with its radical political reliefs and the later tomb of the archbishop.

VISIT:

Metropolis – Lund in the Middle Ages

Metropolis – Lund in the Middle Ages

The Museum of Kulturen i Lund

Historiska museet Vid Lunds universitet

Here some of the finds from Uppåkra are exhibited

APP

SOURCES:

Den Urbana Scenen. Studier och samhälle i det Medeltida Danmark

By Anders Andrén

Acta Archaeologica Lundensia , Series 8, No. 13. Gleerup 1985

Det Medeltida Skåne. En Arkologisk Guidebok

Det Medeltida Skåne. En Arkologisk Guidebok

By Peter Carell

Historiska Media 2007

Lunds Historia vol 1 – 3

By Peter Carelli, Sten Skansjö and Sverker Oredsson

Lund : Lunds kommun, 2012

Kyrkornas Lund

Kyrkornas Lund

By Gunilla Gardelin

Series: Archaeologica Lundensia

Kulturen 2015

Domkyrkan i Lund: en vandring genom tid och rum

Domkyrkan i Lund: en vandring genom tid och rum

By Eva Helen Ulvros, Anita Larsson and Björn Andersson

Historiska Media 2012

English Edition: 2016

Det underbara uret i Lund.

By Lone Mogensen (ed)

Historiska Media 2008

READ MORE:

FEATURED PHOTO:

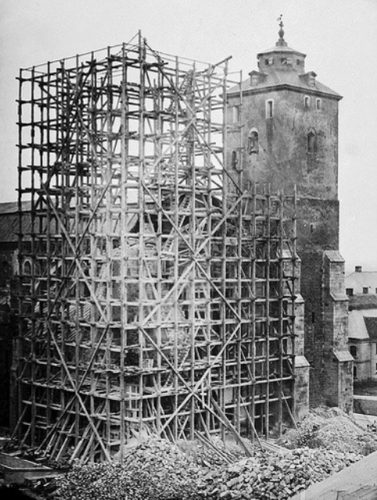

St. Salvator (Drottens Kyrke) in Lund in Scania, Sweden.