In 1639 and 1734, two impressive horns from c. AD 400 and made of gold were discovered at Gallehus near the present border between Denmark and Germany.

The incomplete horns were composed of segments of double-sheeted gold. The longest one discovered in 1639 consisted of seven segments, while the shorter one only held six segments. While the shorter one presented a Runic inscription, the longer one may have featured a hieroglyphic inscription. Likely, the horns were the same size and formed with a winding, helix-like curvature. Both horns also featured a complex ensemble of cast figures soldered onto the outer sheet and engraved ornaments.

The horns were immediately regarded as “Danefæ” – A National Danish Treasure” – and handed over to the Kings, Christian IV and Christian VI. Initially, the first horn was scheduled to be melted down to create a golden drinking horn to commemorate the “ancients”. Fortunately, one of the nobles at court, Joachim Gersdorff, suggested to the king that the horn was already a drinking horn and only needed a plug to render it whole and usable. This was fabricated, and the horn was gifted to the crown prince, who later died due to his excessive lifestyle. The horn held 1.4 l of beer or mead.

Both horns were part of the National Royal Collection until 1802, when they were stolen and melted down, 6.9 kilos in all. Together, they represent the largest find of a golden treasure from the migration period.

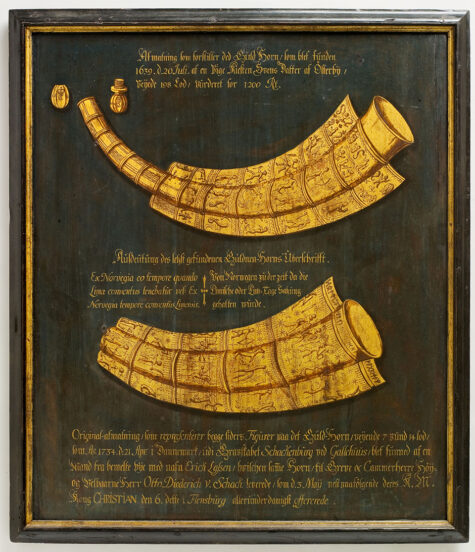

Unfortunately, what remains is only a series of publications with drawings and descriptions from 1641 and 1734. An additional series of casts from the 18th century were also lost, leaving us with a fragmented knowledge of this unique find from the Migration period.

Nevertheless, historians, archaeologists and linguists continue to be mesmerised by the golden horns and their intricate form, the inscription(s) and the ornamentation .

In recent years, new studies have provided further insights. Although the horns will undoubtedly continue to prompt scholars to try and sift through our fragmented knowledge of these curious and enigmatic objects, some studies bring us closer to a better understanding.

The Inscription

Undisputed, the gold horn B from Gallehus, datable to about AD 400-450, bears the following, somewhat placid runic legend: Ek, Hlewagastiz Holtijaz, horna tawidō, this is, “I, H. H., made the horn”. With its alliterations, the inscription also represents the first poetic composition in Proto-Norse.

The Proto-Nordic weak verb taujan* – a causative “to make something, being added together, add together” → “to make, produce” – is unlikely to have had a dedicatory meaning. Some linguists have proposed that taujan* implied a connotative meaning of giving or sacrificing. However, according to a recent comparison of relevant contemporary inscriptions by Robert Nedoma, this additional meaning is not found in the comparable material.

Further, the nominative endings in Hlewagast-iz and Holt-ijaz indicate that the language of the inscription is Proto-Nordic.

The first element of Hlewagastiz appears to be related to Old Icelandic. hlé n., meaning “lee, shelter” rather than to an otherwise unrecorded Germanic counterpart to Gk. κλέ(ϝ)ος translated as “fame” (as has earlier been suggested). The word hlē is known later (c. 600-700) to denote a stone barrier built along the coast to shelter ships. The second element, gast (aisl. gestr), means “stranger” or “enemy” (from Proto-Germanic *gasti- = lat. hostis m.)

As to the second anthroponym, Holtijaz, this is unlikely to be a patronymic “son of *Holtǣ” (if so, the form *Holt(a)nijaz should be expected). Accordingly, from a morpho-phonological point of view, Holtijaz might denote a place of origin – either “of the forest/wood” or “from Holt.

More probably, though, argues Nedoma, we are dealing with the second element of a double name in proto-nordic, Hlewagastiz Holtijaz, with parallels, for example, in Early Germanic: Harigasti Teiwǣ, Ostrogothic: Gunthigis Baza or West Frankish: Berthchramnus Waldo. Such constructions of names are still known (in German, Hans-Jürgen, and Danish, Svend-Erik).

The question, to which linguistic group the inscription belongs – (late) common Germanic, Northwest Germanic, Nordic West-Germanic, Old Norse or even West Germanic – has been hotly debated. The recent study by Robert Nedoma, though, univocally identifies it as belonging to Proto-Norse.

The Ornaments

Specific motifs on the horns are well-documented from later figurative depictions in Germanic Iron-Age and Viking art. Thus, we find a Valkyrie with a drinking horn offering a greeting to an armed horseman entering Valhalla, dancing warriors, and a warrior with a wolf’s head, an ulfhednir. Other motifs are more obviously of Mediterranean derivation, such as the centaurs and the raptors eating fish.

The latter is a motif known from the Black Sea regions and Greek coinage from the 5th century BC. Such eagles were later transformed into Christian symbols of resurrection and salvation and perhaps recycled in a Nordic context on bracteates and even poetry (Voluspá and Hamðismál). The raptor-fish motif may also be found on a sheet or gold plaque from the Staffordshire Hoard, likely stemming from the decoration of a shield.

The motif of the Weapon Dancer is of particular interest. They appear in Sweden, Denmark and Anglo-Saxon England c. AD 400–900. Usually, the male figures wear helmets with horns terminating in beaks of birds, with belts around their waists, and carrying weapons – spears, swords and axes – in both hands. Their more or less naked bodies and their positions give the impression of dancing. Due to this uniform motif, the male figures have been associated with ritualistic dances carried out by warriors gripped in ecstasy while conjuring up Odin and allowing him to transform them into the predatory animals (their totem) – the wolf, the bear, the eagle or the raven. In short, shape-shifting.

Such Weapon Dancers feature prominently at the second Gallehus horn holding spears, swords and axes alternatively. Apparently, they are leading into battle a couple of dressed soldiers equipped with swords. Other motif renditions may be seen on bracteates or foils fitted to ceremonial helmets from the Vendel age (and at the helmet from Sutton Hoo). Likewise, they have been sculptured as figurines. A fine rendition may be seen on the Fingelsham Buckle from the 7th century. Also, a panel on the helmet from the Stafford Shire hoard from the 7th century (cat. 599) is claimed to depict such a scene. Later, the motif can be recognised in the Oseberg tapestry from the beginning of the 9th century and hinted at in the Hákonardrápa and Hàkonarmal from the mid-9th century. Recently, the roots of the Weapon-Dancer Motif have been speculated to date to the Bronze Age. Even if this more speculative conclusion is disregarded, we still see the motif exhibiting a long continuity from the Migration period to the end of the Viking Age.

One of the features of the Weapon Dancers is the horned helmets or headpieces, which end in beaks. The horns on the headgear of the dancers on the Gallehus do not show this feature, but this may very well be caused by the sketchy renditions with which we are left to work.

Of particular interest is also the so-called adventus scene. Initially, the person greeting the rider on a horse was identified by the 17th-century historian, Worm, as a man wearing a priestly robe. However, new studies by Wilhelm Heizmann have univocally identified the person as a woman. Inspired by the Roman motif found on medallions of the Goddess of Victory greeting the conquering Emperor with palm leaves and a wreath, this motif, he argues, was transported into the Nordic lifeworld, where the Goddess of Victory turned into a Valkyrie greeting the warrior with a drinking horn.

As with the recurrent motif of the dancing warriors, we may follow the adventus scene through small figurines, on picture stones from Gotland and in the Scaldic poetry throughout the centuries to come.

To conclude, the Gallehus Horns can be dated to the Migration Period based on the language used in the Runic inscription – Proto-Nordic. Further, we now know that the ornaments represent some of the earliest representations of particular motifs coupled to the mythical Northern life world. We also know these motifs were dominant throughout the next 5-600 years in Scandinavia and its shifting peripheries – Early Anglo-Saxon England and Saxony in Northern Germany. Finally, we know the gold represented a vast fortune, ca. 1650 Roman solidi, a vast sum for the leader of an Iron-Age war-band to have gathered on the battlefields of Europe in the 5th century.

SOURCES:

Zur Runeninschrift auf dem Goldhorn B von Gallehus

By Robert Nedoma

In: Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 19.05.2022

A storm of swords and spears: The weapon dancer as an enduring symbol in prehistoric Scandinavia

By Timmis Maddox

In: Cogent Arts & Humanities 16.04.2020

Das adventus-Motiv auf dem langen Horn von Gallehus (1639)

By Wilhelm Heizmann

In: Bilddenkmäler zur germanischen Götter- und Heldensage. Ed. By Wilhelm Heizmann, Sigmund Oehrl

Walter de Gruyter 2015

“I am Eagle” – Depictions of raptors and their meaning in the art of Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia (c. AD 400–1100)

By Sigmund Oehrl

In: Raptor on the fist – falconry, its imagery and similar motifs throughout the millennia on a global scale. Ed. By Oliver Grimm, Kiel: Wachholtz Verlag, 2020

SEE MORE:

The sets of reconstructions of the Golden Horns from Gallehus exist. Two are kept at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, while one set is on permanent loan to The Museum in Tønder near Gallehus, where the horns were found. Currently a temporary exhibition tells the story of the horns.