This is a crafty and learned detective story of how Christopher de Hamel discovered the personal prayer-book of Thomas Becket in the collection of Corpus Christi College in Cambridge

The Book in the Cathedral. The Last Relic of Thomas Becket

By Christopher de Hamel

Allen Lane 2020

REVIEW

The said manuscript, MS 411, is rather well-known. Dated to the tenth century, it was probably made in Canterbury. Alternatively, it has been noted for its French style. It was handed down to the library by Parker himself, who was Archbishop of Canterbury 1559-75. In a postscript, Parker or one of his scribes wrote that “This Psaltar, in boards of silver-gilt and decorated with jewels, was once that of “N” archbishop of Canterbury [and] eventually came into the hands of Thomas Becket, late archbishop of Canterbury as is recorded in the old inscription”. This “old” inscription is now missing together with a first page lost from the manuscript; perhaps at the time the bejewelled boards were removed. Likely, the first owner was Ælphage (c. 953 – 1012).

The prayerbook itself is not particularly outstanding. In terms of its contents, it was a typical collection of the Psalms, the biblical Canticles, the Lord’s Prayer, the Te Deum, the creeds and some litanies and short prayers. A conventional, yet tactile and graceful book, writes de Hamel, fit for an archbishop’s personal use.

On the following pages of Christopher de Hamel’s book, a carefully written piece of detection is offered to the reader. Enjoyable, and not to be spoiled here in the present review. Let it suffice to say that although every reviewer has not been convinced, I came to believe that yes, Becket did hold this book in his hand when he died. It is simply more than likely that this book was the little “particular” book which Becket just before his flight tasked Bosham “to take care of”… lest when his flight was known to other people, it might be destroyed in the plundering”.

We can no longer smell the man from the dusty pages kept in a library for more than 850 years. But it feels like it, when reading this carefully crafted and charming book on a book.

King Henry’s Bible

In this psalter, Becket would have occasion to repeatedly read a running biblical commentary to such conflicts as those in which he was embroiled.

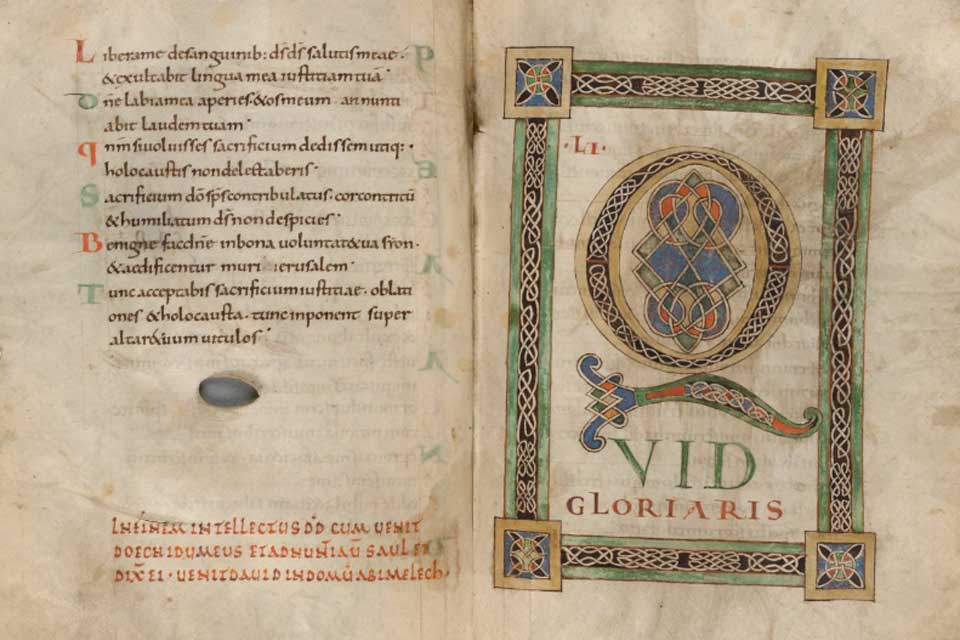

One of the psalms, which may have made a special impression on Becket would be no. 51, where he might read “Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation; and uphold me with thy free spirit. Then will I teach transgressors thy ways; and sinners shall be converted unto thee”. Or from Psalm No 52: “Why boastest thou thyself in mischief, O mighty man? The goodness of God endureth continually”. The latter psalm is the one, which we are told David composed after Saul had caused all the priests in the city to be murdered by Doeg the Edomite. And David was on the run.

In the Winchester Bible, probably made after 1170 and widely believed to have been produced at Winchester for Henry II, this particular psalm is illuminated by a beautiful roundel showing a soldier killing a priest.

Perhaps, Henry had reason to study this painting in detail.

Karen Schousboe