Repositioning a secular legal text like Magna Carta as “sacred” is a prerequisite for making a spectacular exhibition out of it

A first tour to Washington might very well be termed sacrilegious if the visitor only walks the mile from the Lincoln Memorial to the Capitol, but forgets to visit the National Archives at Constitution Avenue in order to inspect the American Founding documents in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom. Something like a neo-classical temple the showcases look like classical tombs, enshrining the holy of holies – the Declaration of Independence.

According to Richard Voase and Barry Ardley, both Lincoln University,who has carried out a study of visitors to the present exhibition in Lincoln of one of the four extant copies of Magna Carta, this is unfortunately not the experience, which people get. Until now the authentic document has been exhibited in a small rather cramped location in an old prison, which – although it is surrounded by sympathetic offers of well-intended introductions to the historical context – does not allow for visitors to experience the document as more than a small, old and unreadable piece of parchment.

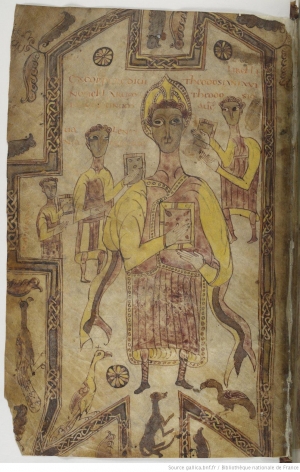

In their highly inspiring article building on insights from sociologists like Émile Durkheim , Walter Benjamin and Daniel Bell the authors demonstrate how a proper exhibition would have to rethink this essentially secular document as a sacred artefact and imparting its renewed aura to visitors, presenting it in a spatial setting signaling gravitas as well as aura.

New vault for Magna Carta

The suggestion is pertinent as Lincolnshire is currently investing app. £20 million on a project called Lincoln Castle Revealed. Part of this project is to create a new vault to showcase the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest and complete this with a cinema space. However, the design does not look at all like a neo-classical Greek temple; rather the inspiration seems to have come from an Anglo-Saxon mound… one wonders to what extent the city was presented with the very clever arguments which can be found in the article: Magna Carta: repositioning the secular as “sacred”?

The new vault has been designed by the architect Andrew Arrol from Arrol and Snell

According to the project the investment should hopefully result in an increase in the overall value of tourism to Lincoln as well as 600 – 1100 new jobs.

Magna Carta: repositioning the secular as ‘sacred’

Barry Ardleya and Richard Voase

International Journal of Heritage Studies, Volume 19, Issue 4, 2013 pages 341-352

DOI:10.1080/13527258.2012.663780

Abstract of article:

Magna Carta is an English legal document, of mediaeval origin. Its salience subsists in the origination of principles such as habeas corpus, trial by jury, and the right of the people to representation in the government. This paper considers how one of the remaining copies, held in Lincoln, UK, can best be presented for public view. The approach is essentially conceptual, underpinned by primary research in the form of an exit survey. The findings suggested some visitor dissatisfaction with the current display. This is interpreted by a discussion of the nature of tourist gazing and anticipation, drawing on the theoretical work of Campbell, Urry, MacCannell and Foucault. A revised presentational paradigm is proposed, drawing on the writings of Durkheim, Benjamin, and Bell. It is argued, with reference to a comparable model elsewhere, that the key to meeting visitor expectations is to re-imagine the Magna Carta as a ‘sacred’ rather than a secular document. The practical implication is to present the document in a way as to generate aura. Forthcoming intentions to re-design the display, to coincide with the 800th anniversary of the signing of the document, add import to the discussion.

READ MORE:

Read about the planned festivities in connection with the 800th anniversary