Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga

Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga

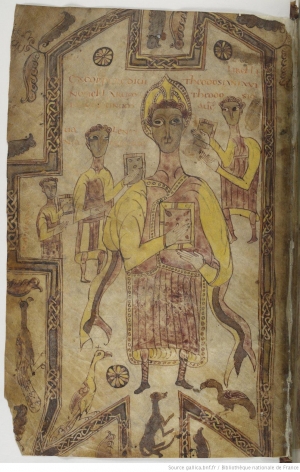

The story of the Viking expansion west across the North Atlantic between AD. 800 and 1000, the settlement of Iceland and Greenland, and the exploration of northeastern North America, is a chapter of history that deserves to be more widely known. Norse discoveries in the North Atlantic are the first step in the process whereby human populations became connected into a single global system. The Norse, and their Viking ancestors, are little known, misunderstood, and almost invisible on the American landscape. Although Norse voyages were known since the early 1800’s, the near absence of physical evidence of Vikings in the New World has rendered the information, and the possibility that Norse explorers reached the North American mainland five hundred years before Columbus, speculative, at best. Yet, discovery of a Viking site in Newfoundland in 1960 confirmed a pre-Columbian European presence in the Americas, and Norse artifacts found in archaeological sites scattered throughout the eastern Canadian arctic and sub-arctic, raise the issue of how far south of Newfoundland the Norse did explore, and what impact their contacts had on Native Americans.

The term “Viking” is indelibly associated with seafaring warriors. Carpentry, and especially boat building, were skills known to all Viking men, and along with maritime skill, was the characteristic upon which Viking expansion and influence depended. Viking craft had an advantage over all other watercraft of their day in speed, shallow draft, weight, capacity, maneuverability, and seaworthiness, giving Vikings the ability to trade, make war, carry animals, and cross open oceans safely. The territorial expansion of the Vikings from their Scandinavian homelands began in the last decades of the eighth century, and started as seasonal raids on the British Isles. Those Vikings who ventured west settled the islands of the North Atlantic. Many theories attempt to explain what propelled Vikings outward from their northern homelands: developments in ship construction and seafaring skills; internal stress from population growth and scarce land; loss of personal freedom as political and economic centralization progressed; but the overriding factor seemed to be an awareness of the opportunities for advancement. By taking on lives as soldiers of fortune, Vikings could dramatically alter their prospects: becoming wealthy, reaping glory and fame in battle, and achieving high status as leaders and heroes based on their own abilities and deeds. Although there is reason for speculation about how far the Norse traveled south of Newfoundland, recent archaeological research provides a solid basis for understanding more about Norse explorations and contacts in the north. Archaeologists found Norse artifacts in early Inuit (Eskimo) sites in the Canadian arctic and Greenland. That people of the Dorset culture had begun to replace their stone blades with metal after AD. 1000 seemed curious, although understood when both late Dorset and Early Thule sites began to produce not only Norse iron and copper, but a host of other Norse materials. Soon Norse materials were reported from many eastern Canadian arctic and northwest Greenland sites dating to the Norse period. These finds suggest that Native Americans interacted with the Norse in a variety of ways: by casual contacts, scavenging Norse wrecks, or outright skirmishes

This volume celebrated the Vikings’ epic voyages, which brought the first Europeans to the New World. In doing so, the ring of humanity that had been spread in different directions around the globe for hundreds of thousands of years, was finally closed. Even though Leif Eriksson’s was not the first—nor the last—voyage of Viking exploration, nor did it lead to permanent settlement in the Americas, his voyage achieved an important and highly symbolic goal that made the world an infinitely smaller place.

This book is a catalogue published in connection with an exhibition in Washington 2000 celebrating the Viking Passage to America in the 1000. It is still worth a read.

Vikings : The North Atlantic Saga

William F. Fitzhugh and Elisabeth I. Ward

Smithsonian Books; First Edition 2000

ISBN-13: 978-1560989950