Stevns is a peninsula in South Eastern Zeeland in Denmark. Flat, although it raises towards the east, it breaks into the sea in the form of high cliffs. Recently, it has been suggested as the location for Heorot, the hall of Hrodgar, and the home of Grendel. What did it look like from the 6th to 10th centuries?

Stevns is a fertile peninsula located south of Copenhagen. Famously, it ends in a 15 km-long fossil-rich coastal cliff, which was listed in 2014 as UNESCO World Heritage. Also, it was recently claimed as the “brimclifu blican” and “beorgas steape” (v. 222) of Beowulf, the sunlit cliffs and sheer crags, in the hinterland of which, Beowulf came to visit Hrodgar.

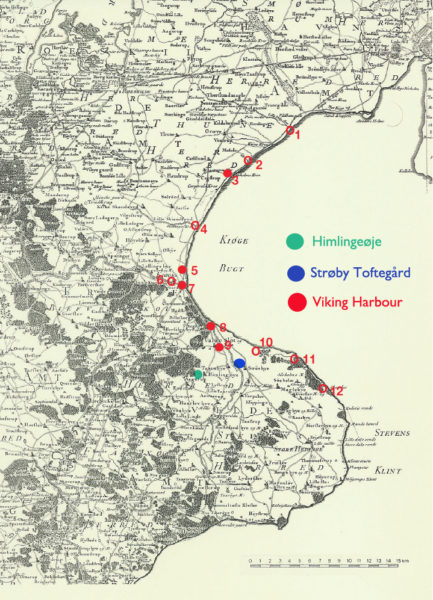

The area is primarily known for its extraordinary Roman finds in graves dating from the Early Iron Age. However, from 1995 – 2013, a magnate’s farm from c. 600 – c. 1000 was excavated at Strøby Toftegård. Although only parts of the excavation reports have been published, an overview may be gained from a preliminary report by Anna S. Beck[1]as well as the work of Sofie Laurine Albris. (See also the presentation at the website “Førkristen Kultpladser” at the National Museum in Copenhagen).

While partly protected from the sea by the forests and cliffs to the east and southeast, the locality was nevertheless accessible for small boats and barges sailing down Tryggevælde Å. The settlement consisted of a large hall rebuilt on a plateau between three to five times. All these halls measured between 37 – 40 meters and consisted of a large hall with additional rooms at the ends. No byres were found in these buildings, indicating their function as ceremonial gathering places.

The plateau had been artificially erected as part of the construction of the buildings. Surrounding the halls, the archaeologists found a ring of cooking-pits – so-called “hørgs” – which yielded an abundance of left-overs from what was obviously ritual feasts. The cooking pits had functioned as a kind of fence or marker in the landscape, segregating the hall(s) from the more ordinary part of the settlement.

Here, some smaller houses, typically with byres and outhouses, and probably organised as separate farms, were located.

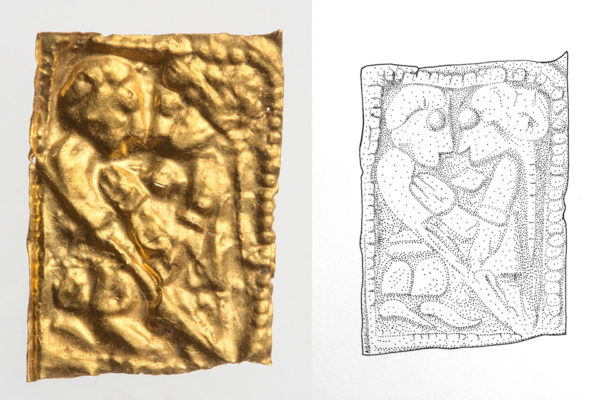

In and around the plateau with the halls, finds were made of fibulas, pearls, carnelian gemstones, tools, fragments of Frankish glass from the 5th to the 7th century, weapons (arrows, parts of swords, spurs), amulets (“guldgubber”), weights, and silver-coins (African, Arabian, Central Asia). Of particular interest are some fragments of silver closely related to the so-called Witham Bowl from the Anglo-Irish context. As such, they belong to the same category of hanging bowls as the famous one from Sutton Hoo.

In the more “ordinary” part of the settlement, finds consisted of pottery and remains of animals as well as tools for spinning and weaving.

The hall of the magnate was located in a landscape of other important settlements – a harbour[2]by the mouth of the river Tryggevælde, a probable shipyard by “Snekkemosen”, another at Vallø Toftegård, a possible market-place at Kastanjehøj, a village near Varpelev and a large mound, Hothershøj from the 5th to 6th century, in the present churchyard of Hårlev Church. It is claimed that the large Viking Runic Stone, had originally been raised on this mound. The stone is dated to c. 900 – 950 and tells of Ragnhild, who was a sister to Ulf, and who raised “this stone, made this mound and built this stone-ship” in memory of her husband Gunulfr, son of Nefir, and a clamorous man”. The same Ragnhild is believed to have been responsible for another stone at Glavendrup in the island of Funen.

All-in-all, the complex at Strøby Toftegård may be categorised as a sacral centre of power akin to those at Tissø, Lejre and Uppåkra. Marked by continuity from ca. 600 – 1000, it holds all the essential elements, including the remains of ritualised festivities (cooking and brewing) as well as an elite lifestyle.

Place Names

This conclusion is furthered by the studies of the place-names carried out by Sofie Laurine Albris in her Phd-thesis[3].

According to her, the place names at Stevns witness to the settled landscape going way back. Approximately half of the place-names can be dated to the oldest category with 50% dated to the Viking Age or later.

A significant early type of names characterised with the Southern Scandinavian suffix, -lev/-löv and often paired with a personal name are prominent in the landscape. The suffix means “that, which is left” and often believed to denote an inheritance. Hence “Gjordslev” means the “inheritance of Gyrth.” Sofie Laurine Albris, though, argues in her thesis that such names, in fact, means not so much the inheritance or property of Gyrth, but rather the land” which he was given or acquired control of as part of his official role, which he was appointed to as part of his alliance with an overlord (king or petty-king). A significant indicator is that these toponyms with the suffix -lev can be found near rich burials or graves. Such is the case for Hårlev just north of Hellested – a sacred place (from hēlaghær = holy, sacred). The presumed farm connected to this grave, though, has not as yet been located.

Interestingly enough, the area in a radius of 3.5 km around Strøby Toftegård is devoid of these older types of names (characterised by the suffixes -lev, -inge, -sted, or –høj). Instead, these names – and especially the names ending on –lev – abound in a radius of 10 – 19 km from the magnate’s centre. We may speculate whether the traditional Roman Iron Age centre further south lost its centrality due to the crisis in the 6th century, leading to the new settlement at Strøby with its corresponding “new” satellites, the –lev villages.

She reveals the way in which this new Germanic Iron Age magnate-centre was surrounded by seven –lev settlements in a radius of 10 km and 4 more at 20 km – to name them: Varpelev, Gjorslev, Hårlev, Vellev (Vallø), Endeslev, Sigerslev, Frøslev, Lyderslev, Alslev, Havnelev and Jørslev.

The same pattern can be found at the magnates’ residences at Lejre, Tissø, and Uppåkra from the same period c. 550 to 1000; yet, specifically not at Gudme, which went out of circulation around the time of the mid-sixth century crisis. Here, it is believed the centre moved further north to “Odins Vi” – present-day Odense.

Sofie Laurine Albris also lists the prefixes of these –lev-names, where they cannot be considered a personal name. The prefixes are *harjar, *saiwa, * Þunrawīhar, Iarl, *frø, wæ/wihar, and goði; or translated – warrior, sea-warrior, priest of Thor, earl, lord, sacred place, or god-man/priest.

If it is correct, as suggested in Albris’ thesis, that these types of place-names, which surrounded the magnate’s residences, indicated places or land, which were “given” to people in the lord’s retinue as part of their entrusted status, we get a fine sense of what “jobs” were available. According to this list, you might be a warrior, a sea-warrior, a priest of Thor or just a priest, set in charge of a sacred place, or “just” an earl or a lord. To fulfil the roles, your over-lord would fit you out with a piece of land or a village. At least, this is a reasonable hypothesis.

Strøby Toftegård may thus have been forged in the crucible of the mid 6th century-crisis leading to the establishment of a new elite centre at a time when the slightly older centre at the Himlingøje complex had utterly lost its significance. This conclusion, though, is as yet hypothetical due to the lack of archaeological evidence, writes Sofie Laurine Albris.

Heorot and Stevns

In a recent, ground-breaking treatment of the poem of Beowulf by one of the most prominent archaeologists in Sweden, Bo Gräslund, he suggests – based on the material culture and other linguistic and semantic evidence – that the poem was composed orally between c. 550 and 600 at the island of Gotland[4]; and that we may trace the sea-faring Beowulf to the peninsular Stevns on his quest for the trophy of Grendel . Albeit already suggested in 1985 by Gad Rausing, Gräslund has definitely explored the evidence further.

Whether or not, the Hall of Heorot was “really” located at Strøby Toftegaard is at best highly speculative. At least, however, the physical attributes of the landscape fits the description with the high cliffs, the rugged shore, the sheer crags, the looming highlands, and later, the beautiful roads, the high-timbered hall “standing on its high ground” – as such halls were prone to do! And with its gold-adorned pillars in the centre (so-called “suler”). Since the golden foil amulets are mainly found in postholes, it is believed they were pinned to such posts, rendering the “timbered hall, splendid and ornamented with gold.“

A titillating thought…

NOTES:

[1] Toftegård – store og små forhold på Stevns.

By Anna S. Beck

In: H. Lyngstrøm & L. Sonne (red.): Vikingetidens aristokratiske miljøer. Tekster fra et seminar i seed-money netværket “Vikingetid i Danmark”. Saxo-instituttet – Københavns Universitet den 29. november 2013. Københavns Universitet. 7-10.

[2]Anløbspladser ved Køge Bugt – fra Vikingetid og Middelalder. By Ulla Fraes Rasmussen. In: Historisk Samfund for Roskilde Amt (2008), pp. 93- 110

[3] Stednavne og Storgårde i Sydskandinavien i 1. årtusind. By Sofie Laurine Albris

University of Copenhagen 2017, p. 205ff.

[4]And probably brought to Britain as part of the ”treasure” accompanying the heathen princess, who married Readwald and whose ”Swedish” gifts were laid to rest at Sutton Hoo. Highly speculative, there is no doubt the poem was orally composed in the 6th century Scandinavia and only later (c. 700) ”translated” into Old English. See: Beowulfkvädet. Den Nordiska Bakgrunden. By Bo Gräslund. Acta Academia Regiae Gustavi Adolphi. Vol 149. Opia 64. Uppsala 2018.

[5] Beowulf, Ynglingatal, and Ynglingasaga. By Gad Rausing. In Fornvännen (1985), Vol 80, pp. 163 – 178

SOURCES:

Toftegård, Sjælland (Nationalmuseet i København)

Stevnsk stormandsgård fra sen jernalder og vikingetid.

By Svend Åge Tornbjerg

In: Årbog for Historisk Samfund for Præstø Amt, 2000, 63-76.

Beowulf. A New Verse Translation

By Seamus Heaney. Bilingual Edition.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2000

FEATURED PHOTO:

Bridge over Tryggevælde river. By I. C. Dahl 18th century. © Statens Museum for Kunst. Source: Wikipedia