Sigtuna is the first proper town in Medieval Sweden. Prior to that, royal complexes like Uppsala and trading emporia like Birka served as regional centres.

Sigtuna near Skarven was strategically located on the northern coast of the archipelago of Lake Mälaren, facilitating and controlling access to Uppsala by ships or ice-sledges. Located 30 km from both Gl. Uppsala and Birka, the town was founded c. 980 as a new political centre, preceding Stockholm. With large parts excavated in the 20th century, the history of Sigtuna provides an essential inroad into the very early history of the state-formation of Sweden. Apart from the trading emporium Birka, Sigtuna is arguably the very first urban settlement in early medieval Sweden. Birka was abandoned sometime between 960 and 70, and Sigtuna was probably founded as a successor to Birka, but with a distinct role as controller of the access to the hinterland (Uppland). Dendrochronology has provided us with a date, 981, for some of the buildings in the centre of the town.

Sigtuna may have been a successor to the royal residence at Fornsigtuna (Old Sigtuna, Sithun, Signildsberg or Signesberg) located 4 km to the west of present-day Sigtuna.

Snorri Sturluson tells us in Heimskringla that Odin “took up his residence at lake Mälaren, at the place now called Old Sigtun. There he erected a large temple, where sacrifices were organised according to the customs of the Asaland people (the Æsir). He appropriated to himself the whole of that district and called it Sigtun. To the temple priests, he also gave domains. Njord dwelt in Noatun, Freyr in Upsala, Heimdal in the Himinbergs, Thor in Thrudvang, Balder in Breidablik; to all of them he gave good estates”. Snorri, writing in the 13th century was copying ancient stories or myths. Archaeologists, though, have found evidence of large (royal?) settlement four km to the west of modern Sigtuna. With two large three-aisled halls, a series of terraces, traces of a harbour, a large mound or Thing, and several smaller grave fields, archaeologists have dated the settlement to c. 750 – 800. The complex is considered a forerunner of Sigtuna, a royal foundation from c. 970 – 80. Some historians and archaeologists have hypothesised that Uppsala, Fornsigtuna, and Birka each functioned as a central place for local petty kings. (One such is mentioned in Ansgar’s Vita by Rimbert).

The name probably means “wet place” or “swamp” (“Sik or Sig”) while “Tun” refers to a “plot” or “place” inhabited and owned by a representative of the elite, a local chieftain or clan-leader. Another etymology implies that “Sig” means “victory” (“Seger”) referring to one of the bynames of Odin. The name – Situne Dei or God’s Sigtuna – is later recorded on coins minted c. 995 – 1030. The village, Fornesitune, is mentioned in a letter from c. 1170, in which the Pope demands that the Swedish king returns the village to the bishop of Uppsala, who had taken over the diocese during the 11th century.

Today, c. 8000 people live in Sigtuna. In 1000 -1050, based on the number of excavated graves it may – at any time – have amounted to c. 750. Based on the number of plots (c. 180), though, it likely exceeded a thousand inhabitants.

Early History

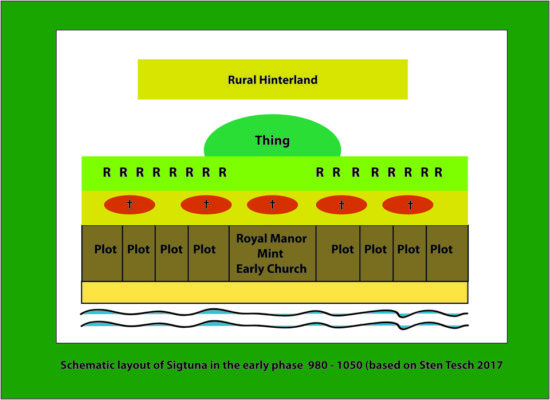

Based on excavations, Sigtuna consisted of a nucleus of large houses located along the narrow beach of Mälaren, with a rocky and wooded ridge to the north. Beneath the ridge was located approximately 25 separate Christian burial grounds. At this time the sea level was five meters higher, and ships could enter the archipelago from the Baltic. At first, the buildings on the plots seem to have been oriented towards the beech. Later, in the 11th century, the cityscape changed its orientation towards the main road cutting through at the back.

The houses differed from those in the surrounding countryside by being erected on long and regulated narrow plots on each side of the main street. One plot would be filled with a hall building as well as smaller houses with living quarters and workshops. The plots with a length of 20 to 40 metres would be divided by narrow alleys measuring between 1,5 to 2,5 metres long or narrow pathways allowing from the rain dripping from the eaves. More than 180 houses have been archaeologically demonstrated.

In the early phase, a plot would hold a hall with a hearth and a small cabin, with the hall turning its back on the main street, indicating the orientation towards the beach-front. Likely the main street did not feature in the first settlement. Fifty years later, c. 1050, the hall would be moved to the back of the plot with a succession of smaller houses covering the area between the main street and the hall. These houses would be used as workshops, with living quarters behind, and halls to the back. The houses from the first period, when the plots were organised towards the beach, were half-timbered. In the later phase, the buildings became sturdier, were built of logs and with roofs covered in turf. The regulated layout indicates the planned character of the settlement.

Legend has it the town was founded by King Erik the Victorious (Erik Segersäll or Eiríkr Sigrsæli) † 995. According to later sources, his byname heralded from a mighty battle at Fyrisvallarne where he victoriously fought his brother Styrbjörn. He is said to have converted to Christianity as well as relapsed. This Erik was married to either Sigrid Storråda or Gunhild, a sister or daughter to the Polish King Boleslaw; or both. His widow (whether one, the other or both) married the Danish king, Sweyn Forkbeard. The sources, though, are vague and conflicting. We do know, though, that the son of Erik, Oluf Eriksson Skötkuning minted the first Swedish coins at Sigtuna, likely near a royal manor in the middle of the first settlement and the later location of the very early church in town. The silver, which went into this large-scale minting operation probably derived from the payment of Danegeld in England during the Danish conquest of England by Sweyn and Cnut, Oluf’s half-brother. Another source of silver may have been the vigorous trade along the easter route to Kiev, Byzantium and even Bagdad, to which a number of the exotic finds witness.

Significant pieces of jewellery excavated in the 1960s, a bronze matrix, a pendent and a carved elk-pommel have questioned this story. The pendant is identical to one of those found at Hiddensee, while the matrix would have been used to produce brooches similar to the large fibula found in the same hoard.

The presence of these jewels tells us that a Danish goldsmith from the Jelling dynasty likely sojourned at Sigtuna during the very early years of the town (970 – 80). Might the town of Sigtuna have been founded by Harold Bluetooth, as has been suggested? The regular layout of the town is in itself a significant witness to the close connections between the rulers at Sigtuna and the Jelling dynasty, which is known for its sophisticated building projects at Jelling as well as the Trelleborgs. Or was it founded by the Swedish magnate Skagul Toste, who is recorded to have received part of the “Danegeld” paid out in 970? And whose daughter (Sigrid Storåde) may have been one of first Erik’s and later Sweyn’s wifes? Another magnate, mentioned on aRunic stone in Uppland, Thorkell the High, also belonged to the inner circle of the Jelling Dynasty. Inspiration from Jelling may have filtered into Sigtuna through any of these chieftains.

Early Christian Settlement

Sigtuna, though, was not just a royal town. It was also a very early Christian settlement, probably planned to act as an alternative sacred centre to such ancient pagan settlement as Fornsigtuna, which later sources tell us was owned by the bishop at Sigtuna. It may also have been erected as a direct reaction to Uppsala.

At first, Mass was celebrated in the major, private halls regularly found at each plot, while the dead were buried to the north in approximate twenty-five small burial grounds with c. one thousand graves from 980 – 1050. These distinct “cemeteries” were characterised by their distinct and separated character as well as the lack of churches. Burial custom, as well as the runic stones, clearly indicate the Christian character.

From this period a particular group of archaeological finds invites us to imagine how the early Christian life might unfold in a missionary outpost in the late 10th century. The group of finds consists of nine small tiles of green porphyry or serpentine excavated from the private homes or halls located along the main road. Such stones had been quarried in Greece in Antiquity. Later, they were scavenged in Rome and elsewhere as spoliae and reused as sacred stones in portable altars, petrae sacrae. It has been suggested that the tiles from Sigtuna derived from the ruins in Cologne. Similar fragments of stones have been found in Haithabu as well as later Schleswig. Particularly interesting is that these fragments of tiles were found in both Haithabu and Sigtuna in private homes, indicating the existence of private churches or chapels; or perhaps the double function of the halls as both banqueting venues and churches. Possibly some of the plots in Sigtuna with their halls belonged to the new Christian elite of priests.

The tiles were found in contexts dated to the 11th and 12th centuries, prior or contemporary to the period when wooden churches dominated, but before the construction of the six or seven regular stone churches took place. These churches were built along a new street – Prästgatan or Vicar’s Street – running to the back of the interior plots. We know that regular cemeteries came to surround these early churches built amid the former burial grounds.

In 1064 we hear of Adalvard the Younger, the first Swedish bishop in Sigtuna. His cathedral was likely constructed of wood. It was not until c. 1100 the building of the first stone cathedral was commenced. To whom it was consecrated is not known. The cathedral was likely located at the centre of the town next to the old royal manor with its impressive mint. The surrounding cemetery is characterised by burials holding individuals which apparently had enjoyed a somewhat better diet

On the other hand, which church functioned as the cathedral has been disputed. Thus, recent excavations beneath St. Laurentius (St. Lars) have revealed a bishop’s grave as well as fragments of a baptismal font.

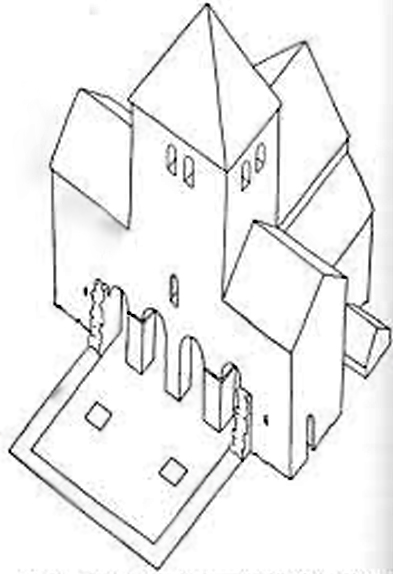

The plan of this church as well as the contemporary St. Olaf’s and St. Peter’s, was nevertheless peculiar. The choir with a rounded apsis was square and of equal size as the nave. A major (perhaps fortified) keep towered over the crossing. The tow other churches, St. Olav and St. Per (now ruins) were built at the same time and with the same ground-plan. Later, longer naves were added.

It has been suggested that the three churches functioned as corresponding liturgical endpoints of a royal processional route, beginning with a formal (re)coronation at St. Per, which was located near the new royal manor to the west, and ending in the crypt to St. Olav, venerating a precious relic. In between, a station was the cathedral at the centre of the old town, St. Lars (Lawrence).

In 1070, Adam of Bremen called the town a Civitas Magna. This lasted until 1164 when an independent Swedish Archbishop was appointed at Uppsala. Nevertheless, Sigtuna continued to prosper and in 1214 – 15 it even regained the upper hand, when the archbishopric was planned to return from Uppsala. During the 13th century, the town nevertheless went into decline, until it is mentioned in 1311 as a Villa Forensis (market town). At this point, the town was reduced to a small rural town, eclipsed by Stockholm and the Arch-Diocese at Uppsala.

The Coins

The location of the mint by archaeologists rests on spectacular finds of dye- stamps and other refuse from the production of the well-known coins minted by Oluf Skötkuning 995 – 1015. The mint was excavated in the 1990s. Based on the number of dies (at least 200) it has been calculated that a couple of million coins were minted in Sigtuna during his reign. Based on the English design used for these coins, the mint masters likely originated in England as did some of the metal. It has been estimated that a couple of tons of silver were minted during the reign of Oluf Skötkuning. This might be compared to the estimated 110 tons of silver, which derived from England during the conquest of Swein and Cnut at the turn of the millennium. The silver involved in the Sigtuna-minting may have been less, though, if the king used the mint to tax the merchants visiting the town through the managed recalls and reminting of his coins. At this point, we don’t know. Nor do we know whether some of the silver did in fact herald from the lively trade in Russia and further south.

It has been argued that the residents at Sigtuna were former “mercenaries” in Sweyn’s and Cnut’s armies, who turned their silver into the new mint to acquire the common coin issued by their leader, Oluf Skötkuning. Or used the silver to pay for the right to acquire a plot in his new and very modern town. Weighing the coins, it appears they differed significantly. Likely, they were still weighed when used, which does pose the question of why they were even minted? Were they foremost prestigious tokens used by the elite chieftains as signs demonstrating their membership of the retinue of the new Swedish king, Olaf Skötkuning? Or were they circulated as proper payment for goods and services? The few finds of coins in the wider excavations at Sigtuna as well as in the rural hinterland does indicate that proper money economy was still in its infancy.

It has been suggested that the byname (treasure-king) simply meant “mint-king”. We know from the coins that Olaf was initially called “King of Sigtuna”. Only later in his reign, he was named King of the Swedes.

People

But who were the people living in Sigtuna at this time? Recently published studies of aDNA and strontium isotope ratio of 31 individuals found in the burial grounds and cemeteries to the north have revealed a mixed composition with a high genetic diversity and non-local origin of these people. It appears they derived from Iceland, England, Estonia, Russia, Ukraine, the Balkans, Sardinia, Galicia, Sicily and Malta. Although 70% of the females studied were deemed non-locals with 66% males considered locals, the study did not demonstrate a statistically significant pattern of exogamy. Heterogeneity was ubiquitous and reflecting a cosmopolitan mixture, is the conclusion.

To some extent, this pattern is reflected in the diet consumed by the town’s inhabitants. Studies have found that groups of people interred in the different burial grounds differed as to their food. In this study, 80 adult individuals found in three separate cemeteries representing the different phases of the town – foundation, prosperity and decline – were analysed.

The first phase or period was represented by individuals interred in one of the burial grounds (near Nunnan) without a church. Included in this segment were also the individuals buried near one of the the churches (St. Lars). Interestingly enough, these two groups of individuals differed in their diet according to their social status. Thus, the cemetery in the city centre next to the later cathedral obviously represented a population with a higher status. It seems a distinct social hierarchy might be detected. The study demonstrated that the intake of protein was high and that this mainly derived from land-based sources. However, gender differences might also be detected. Women were generally not as well fed as the males, partaking of more vegetables and less prestigious animal protein. In the second phase, the females near the church were allowed more protein, while the males presented a more varied dietary pattern. Perhaps this difference is consistent with the hypothesis that the males might exhibit a more mobile lifestyle as travelling merchants. Or they may have been regular guests at the royal feasts!

The Runic Stones

More than 40 rune stones or coffins – either in fragments or still standing – have been found in Sigtuna. Of these approximately 17 are still standing near or close to the old burial grounds and churches to the north. It appears they were primarily erected along an open road leading up to the presumed Thing situated on a steep hill to the back of the town. Still offering up their prayers for the deceased, they make Sigtuna the locality marked by the densest proliferation of these monuments. And while the genetic studies of the buried individuals tell us of a cosmopolitan population, the stones tell a somewhat different story. In the inscriptions, we meet several individuals with Scandinavian names. For instance, we meet Gillög (Gillaug), Kusi, Torbjörn, Esbjörn, Asbjörn, Styrbjörn, Dyrver, Sven, Assur, Germund, Ofeg, Tora (Torhild or Thorgunn), Rodvi perhaps from Gotland, Frödis (name only known from Vinland), Ulv, Grimulv, Anund, Orm, Sibbe, Orökja, Tyra, Illdori (evil Halldor), Sigsten and Holsten. To name a handful.

These rune monuments thus witness indirectly to the hypothesis by Sten Tesch that Sigtuna was a ritual and administrative centre owned by the king who rented out plots to his magnates, otherwise living on their manorial farms in the hinterland, but using Sigtuna as a common meeting ground for business and judicial affairs as well as business enterprises. Earlier in the 10th century, they would have met up at Fornsigtuna, but by establishing Sigtuna as the new centre, the king would further his position as supreme arbiter. Traditionally, these magnates and their families were not buried at Sigtuna but at home in their family’s or kin’s burial ground next to their manorial farm. As part of this practice, memorials may have been raised at Sigtuna to commemorate and mark out the sphere of influence of these Scandinavian chieftains and their family members. Yet, Runic Stones continued to be part of the memorials in the countryside as well. It should be noted that although a couple of Runic monuments specifically mention men who were guild brothers in the “Frisian Guild”, their names – Albod and Torkel – tell us they were Scandinavian tradesmen or partners in this Frisian enterprise. And probably belonging to the local elite.

One hypothesis, thus, is that Sigtuna was a trading post and owned and exploited as a political centre by the king and his magnates, who were otherwise living on their manorial farms in the hinterland. Another idea, though, has been based on a study of the ceramics found at Sigtuna and elsewhere. Based on these finds, the town was inhabited by locals during the first 30 years. This conclusion fits well with the general lack of traces of trade and craft production in the early phase. From around 1010, however, households in the town seem to have adopted more prestigious and international ceramics (so-called Baltic Ware). It has been suggested that potters (slaves) from Kiev were responsible for the introduction of this new style . What we also know is that these ceramics have not – so far – been found in the countryside. Nor have an abundance of Byzantine or international artefacts been excavated at these large and obviously wealthy farms or manors in the countryside. Town and country belonged to different cultural spheres, it seems.

As opposed to this theory, however, it has been noted that the town must have been dependant on victuals delivered from the countryside. Sigtuna was not a rural town, but rather a commercial, ritual and administrative hub strictly dependent upon the regional support of the magnate’s large farms or manors lying behind the rocky ridge to the north, notes Sten Tesch, who was responsible for the Museum at Sigtuna from 1985 –2010, and has supervised numerous excavations in the town.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Viking carved from Elk Horn. The Sigtuna-Viking is unique. Measuring only 4 cm, it seems to have been left unfinished. Its future use is unknown. A new hypothesis by Uaininn O´Meadhra suggests that it is a representation of St. Olaf. © Sigtuna Museum

SOURCES:

In English:

Sigtuna: Royal Site and Christian Town and the regional Perspective, c. 980–1100.

By Sten Tesch

In: New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. AD 750 – 1100. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th2013. Ed. by Lena Holmquist et al. Archaeological Research Laboratory, Stockholm University 2016.

Vyer från medeltidens Sigtuna/ Images of Medieval Sigtuna / Ansichten von Sigtuna im Mittelalter / Vues de Sigtuna au Moyen Âge

By Sten Tesch and Jaques Vincent

Sigtuna Museers Skriftserie 10, 2002.

Dietary patterns and social structures in medieval Sigtuna, Sweden, as reflected in stable isotope values in human skeletal remains

By Anna Kjellström, JanStorå, GöranPossnert, and AnnaLinderholm

In: Journal of Archaeological Science, vol 36, no 12, pp. 2689 – 2699

Genomic and Strontium Isotope Variation Reveal Immigration Patterns in a Viking Age Town

By Maja Krzewińska, Anna Kjellström, Torsten Günther, Mattias Jakobsson, Jan Storå, Anders Götherström et al.

In: Current Biology, Vol 28, no 17, 2018, pp. 2730 – 2738

A Rune Stone Walk in Sigtuna

Sigtuna Museum

In Swedish:

Sigtuna Museum has also published a list of freely available articles

Fornsigtuna, En kungsgårds historia.

By Agneta Allerstav ..

Upplands-Bro fornforskning, 1991

Sigtuna – Det Maktpolitiska och Sakrala Stadsrummet under sen Vikingatid och tidig medeltid (c. 980-1200)

By Sten Tesch

In: Människors rum och människors möten. Kulturhistoriska skisser. (2007)

Folk och rövare I Sigtuna stad. Danagäldernas roll vid samhälsomvälvningen omkring år 1000.

By Rune Edberg

In: Situne Dei. Årsskrift för Sigtunaforskning och historisk arkeologi 2006

Frötuna, Håtuna och Fornsigtuna. En uppsats om tre tunagårdar I Uppland och deras betydelser mellan 200 -1000 e. Kr.

By Tom Oden Ahlquist

Kandidatuppsats I Arkeologi, Stockholms Universitet 2011

Tidigmedeltida sepulkranstenar I Sigtuna – Heliga stenar från Köln för såväl hallkult som mässa I stenkyrka.

By Sten Tesch

In: situne dei. Årsskrift för Sigtunaforskning 2007