In the Frankish Annals, we read about Saxon and Slavic rebellions to the north involving several Danish kings. Who were they? Also, how should we characterise their way of life?

In 804 Charlemagne brought the Saxon wars to a close, by uprooting and displacing 10.000 men, women, and children. Living both south and north of the Elb Estuary, the aim was to remove insurgents, create a buffer zone between the Danes and the Frank, and to people it with Slavs.

Not only did this once again lead to Saxon refugees seeking north. It turned the Danish King Godfred to call upon his fleet and his cavalry to withstand this incursion into his sphere of interest.

Followed by a series of events, Godfred appears to play a prominent role, which has enticed historians to try to flesh out this enigmatic king of the north. Sending out his tentacles to the south and the east at the cusp of the Viking age proper, it is fascinating to uncover his story.

First to note is that Godfred was called “rex” (king) as opposed to Thrasco, the Duke of the Obodrites; as was his father (or brother?), Sigfred, whom we meet for the first time in 782. Apparently, the Carolingians considered the leaders of the Danes to belong to a different league. While dukes were supposed to meet up at the court of Charlemagne and present themselves as subservient, kings called for a somewhat different set of attitudes.

Known to the court of Charlemagne from 782, when Sigfrid was harbouring both the Saxon rebel Widukind and numerous other fugitives, this Danish king later came to feature in a couple of poems as a pompous or grandstanding (pompifer) man, who waved his spectre over a godless and accursed kingdom and whose comeuppance was secure: in the end, they prophesied, Sigfred was bound to arrive at court with his hands tied behind his back. Neither Thor nor Odin (Thonar et Waten) would help him, they claimed. These two sniggering poems were written sometime between 783 and 787 by Peter of Pisa (AD 744 – 799) and Paul the Deacon (AD 720 – 799) . Characterised as occasional poems, their main objective was to stage the authors’ civilised superiority towards this northern king, whom they compare to a wild and hairy “beast”. As an undercurrent, we nevertheless get the impression that Sigfred was regarded as a significant opponent. During the Saxon wars he seems to have aided and abetted his southern neighbours against Charlemagne. Why else write derogatory and defamatory poetry about him? The Carolingians must have been wary of Sigfred; as they came to be of his son(?) Godfred.

Godfred

Sometime between AD 799 and 804, his son (or brother) Godfred must have taken over. In AD 804, we meet him mustering his fleet as well as cavalry at Sliesthorp (the bottom of the Schlei near the future Haithabu). Godfred is undoubtedly prepared to defend his realm against the Carolingian transgressors, who not only intend to control the region north of the Elbe by setting up the Duke of the Abodrites, Thrasco, as a buffer against the Danes but also want to stop the fleeing Saxons to find refuge up north.

From the Frankish Annals, we get the impression that Godfred was a smooth operator. He and his advisors knew that to meet up with Charlemagne in person was the same as to subject oneself to vassalage and payment of tribute. Hence, despite an invitation to meet up with the Emperor, Godfred kept his distance while plotting for the future. Four years later, the king once more took action and mounted an expedition against the Obodrites by sea. Setting up quarters along the coast of future Holstein, he attacked and took many Slavic fortifications, expelled Thrasco, and hanged another Slavic duke, Godelaib, from the gallows.

Although Godfred – according to the chronicle – suffered from severe losses, he finished the campaign by destroying the trading emporium called Reric near Strömkendorf north of Wismar and moved the merchants to the future Haithabu near the harbour of Sliasthorp. In the Frankish Annals, we read that he stayed there to fortify the border of his kingdom with a protective bulwark from the Baltic Sea and along the Northern Bank of the River Eider.

This bulwark – Danevirke – has been archaeologically dated to the end of the 6th century. The dyke reached from the bottom of the Schlei Estuary and along the northern tributary of the River Eider until reaching the Eider-Treene Depression with its brackish tidal foreland, swampy moors, streams and river valleys. Repaired in AD 727, Danevirke was cut through by the main road from north to the south called the “Road of the Army” or “The Road of the Oxen”. Right at the crossing to the east, we are told that Godfred erected a single gate through which wagons and equestrians would be able to leave or enter his realm. Recently this gate has been documented archaeologically.

The following year saw Godfred seeking reconciliation with Charlemagne. At least, this is how the Frankish Annals “frame” the event. As it happened, a diplomatic meeting was set up north of the River Elb at Beidenfleth with counts on both sides attending and with hostages exchanged. At this point, Charlemagne decided to erect a fortified outpost on the northern side of the River Elbe at Burg Esesfeld (at Itzehoe, north of Beidenfleth). In the Frankish Annals, we hear in details how he decided to garrison the new castle with a Frankish force led by one of his trusted men Egbert. Meanwhile, Thrasco was killed by Godfred. Matters were obviously coming to a pass.

Then, in 810, while Charlemagne was still pondering how to deal with this king, a fleet of 200 ships landed in Frisia. The Annals tell us that all the islands off the coast of Frisia had been ravaged, that the army had already fought three skirmishes, and that the victorious Danes had been paid 100 pounds of silver as a tribute. Meanwhile, Godfred was still at home. Likely, this led Charlemagne to fear a simultaneous attack across the Elb and to gather an army. Personally crossing the River Rhine at Lippeham, the Emperor took to the saddle moving his troops to the confluence of the rivers Aller and Weser. Nought came of it, despite Godfred’s threats that he would meet the Emperor in open battle. As the story unfolded, the fleet returned home, while one of Godfred’s retainers or kinsmen killed him. In his biography of Charlemagne, Einhard neatly summed up the events of those years:

“Charles final war was the one taken up against the Northmen, who are called Danes. First, they had operated as pirates, but then they raided the coasts of Gaul and Germany with larger fleets. Their king, Godfred, was so filled with vain ambition, that he wowed to take control of all Germany. Indeed, he already thought of Frisia and Saxony as his own provinces and had [first] brought the Abodrites, who were his neighbours, under his power and [then] made them pay tribute to him. He even bragged that he would soon come to Aachen, where King [Charles] held court, with a vast army. Some stock was put on his boast, although it was idle, for it was believed that he was about to start something like this, but was suddenly stopped by death. For he was murdered by one of his own attendants and, thus, both his life and the war he had begun came to a sudden end at the same time.”

From: The Life of Charlemagne by Einhard, ch. 14, 9 p. 24. In: Charlemagne’s Courtier. Transl. By Paul Edward Dutton. Broadview Press 1998.

Pompous Asses or Ferocious Kings?

Looking at the epithets attached to these two kings helps us to get a feeling for how the Carolingian court envisaged these men. Fundamentally, they were regarded as savages. Thus, in the poem by Peter of Piso, Sigfred was characterised as a king with more bluster than muster. Pompifer, he is called. Not an adjective often used, it derives from pompa, which means procession or just in general ‘pomp’ as in ‘Pomps and Circumstances’. Cicero used it to describe a kind of rhetoric, which had gone off the wall. To this should be added the list of adjectives applied to the king by Paul the Deacon, in his poetical reply to the first poem. Here Sigfredd is characterised as truculentus, brutus, indocto and hirsutus, that is as a ferocious, brutish, ignorant and hairy (unkempt) “kind of animal”.

This slightly “insane” quality may also be found in the characterisations dealt out to his son (or brother), Godfred, whom we are variously told was filled with vain ambition (vana spe) as well as pride (superbia) and ostentatious bragging (iactantia); or might even be considered mad (vaesenus). Especially Einhard in his biography of Charlemagne writes of a braggart filled with idle threats, who believed that he was lord of not only Frisia and Saxony but intended to take all Germany.

Of this handful of characterisations, though, the epithet “vaesanus regi” is perhaps the most illuminating. Lifted wholesale by the unknown author of the Frankish Annals, it seems taken from a poem by Lucan, which seems to have occupied the minds of the scholars and intellectuals at the court of Charlemagne, the Pharsalia, also known as De bello civili. Composed after AD 61, it centres on the battle of Pharsalia when Caesar decisively defeated Pompey the Great. In book ten, Caesar is compared to Alexander, and here we find the verse describing how the latter died, and his mad reign came to an end; just as was the case with Godfred, who at the end of his life sought to attack Charlemagne in his lair near Aachen.

Did the courtiers and historians at the court of Charlemagne slowly come to think of these Scandinavian kings as wild warriors in the mould of both Caesar and Alexander? As opposed to the just and civilised Charlemagne, who ruled after their own heart? And hence, as less ferocious, uncivilised and slightly ‘mad’ animals?

This shift in the interplay between the two rulers, Charlemagne and Godfred, has recently been evaluated by respectively a German and American historian.

In his thesis, Volker Helten writes about the” disproportionality” (Unverhältnismässigkeit) between the two reigns. Helten sees the acts of Godfred as reactionary less than aggressive. To some extent, this is also the understanding of Daniel Melleno, who considers Godfred’s kingdom as a “secondary” state, whose rulers were engaged in a practice dubbed imitatio regis Francorum. However, he also considers them rulers, whose descendants from the 820s came to be quite deft at manipulating some of the technologies of power to their own satisfaction. Central to this project was the growth of Haithabu and its role as one of the significant emporia in Scandinavia, of which the others were Ribe, Birka, and Kaupang.

Haithabu

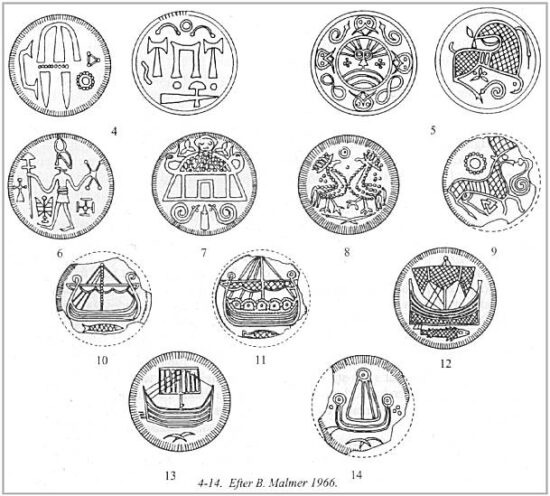

Undoubtedly, Haithabu (Hedeby) soon after its foundation by Godfred became a thriving trading centre catering for merchants and tradesmen from both east and west selling Frankish ware, glass, and weapons as well as Scandinavian crafts as well as fur, amber and even Arabic merchandise from the Middle East. One of the critical elements furthering this trade was the so-called “Birka or Hedeby coins”, with the name of this coinage reflecting earlier nationalistic tendencies to identify the location of the mint as either “Danish” or Swedish”. Later, these coins were more carefully studied and found to represent a collection of Nordic takes on Carolingian types. Thus, Frankish ships would be redrawn as Viking vessels, while pictures of Viking halls would replace the Frankish temples. Were these coins derivates? Or near-contemporary to their Carolingian models? If so, the Nordic and Carolingian coins should perhaps be considered as fascinating “speech-acts”, enacted in a continuous cultural dialogue between the two ruling powers – the Carolingian Empire and the up-and-coming Nordic Viking World. While the ships on the Carolingian or Frisian denars from were those known to sail in the Rhine estuary, the ships of the Nordic coins were depicting authentic Viking ships. In the same manner, the four-legged deer-coins and the “Beserker” or “Striding Man from Tissø” with his horned helmet clearly belong to a Nordic assemblage of motives. Also, the reuse on the obverse of the so-called Wodan-mask known from the 8th-century sceattas from Ribe indicates a conscious effort to create a “culturally” and historically informed rejoinder to the Carolingiancoins featuring the portrait of the Emperor.

Was Godfred active in launching this new coinage? In a Scandinavian context, this has been debated since the 1980s. Numismatists have argued by referring to Birka and Haithabu as the likely candidates for the mint(s). Since Birka was outside the political sphere of Godfred and Haithabu’s foundation was set to AD 808, it has until now seemed unlikely that the king might have had an actual hand in the foundation of the mint.

A recent find at Ribe from 2018 of a very significant hoard of pristine coins from c. 800 – 820 may, however, shed new light on this fifty-year-old question. The hoard consists of 252 pristine coins found in a wet meadow directly south of Ribe. Likely these coins were minted a Ribe and not elsewhere. Any travelling merchant would have a purse filled with a mixed assemblage of coins, but not a mercenary or Viking paid in the King’s coin at the end of his service and at Ribe. We cannot know for sure that the coins were minted at Ribe reusing the silver derived from the tribute, which Godfred’s navy had commandeered in Frisia. But it is perhaps likely?

In this connection, it is intriguing that the coins feature the “Wodan-Masks” on the obverse – a hairy, wild-eyed and ferocious-looking God or man. Perhaps the portrait of Sigfred as it was rendered in the poems was not far off from how a proper Viking hero should look? Might it even be a stylised portrait of Godfred, rendered differently from the Roman imperial portrait of Charlemagne? Or did the two intellectuals at the court of Charlemagne handle a scaetta from Ribe and used it as inspiration for their poetic slander?

Erik’s Hill

A recent discovery of a royal seat near Erritsø probably shed even further light on the life-world of these rulers. Erritsø literally means Erik’s Hall and likely refers to Godfred’s son Horik, who ruled Denmark from c. 828 to 854. The new excavations seem to indicate that a series of massive halls were part of continuous habitation on the location from the 7th century and onwards into the end of the 9th century. As the layout of these halls with their attached annexes (or temples) is perfectly mirrored at Tissø and Lejre (and probably Funen), archaeologists are now speculating whether a “royal designer” was at large at this early time in the history of Denmark.

Might this indicate that when the Carolingian court referred to these men as the “Kings of Danes”, they were actually reading the landscape correctly?

The received wisdom is to claim that Denmark around this time consisted of a number of distinct “minor kingdoms” – with headquarters at Tissø, Lejre, and Uppåkra. Not until the reign of Harold Bluetooth do we get a firm idea of Denmark as a nation-state. However, the dimensions and layout of the newly excavated hall at Erritsøe reopens this question. It appears that the layout of the site as well as the design of the hall to perfection mirror the equivalent sites at Tissø and Lejre. If so, we may ask if they were in fact royal sites used by an itinerant Danish King ruling most (all) of what was later to be regarded as “Denmark”? No more than a hypothesis, it seems to be an idea gaining more and more traction.

Rex Danorum and the Realm of Denemearc?

The earliest description of “Denemearc” derives from two travel memories from ca. AD 890–899. In these reports, we hear of the sea voyages of two merchants, the Norwegian Othere and the English Wulfstan.

Both mention the geographical region “Denemearc”, the land along the coast from the bottom of the Firth of Oslo to the south of Scania. Since “mearc” or “mark” (“udmark”) originally denoted borderland, this part of the description may be said to refer to the border region of the Danish realm. Elsewhere in these texts, we hear that Langeland, Lolland, Falster and Scania “all belong” to “the Danes or alternatively to Denemearc. At this point – at least in the mental map of the two travellers – the home of the Danish people consisted of the islands as well as (at least part of) Jutland and the coastline along present Sweden. Pretty much the outline of the realm later known as “Denmark”.

Might we imagine that Sigfred and Godfred ruled over a people living more or less inside the later “Kingdom of Denmark”? As it appeared in the sources from the 11th century and onwards?

The descriptions of Othere and Wulfstand are ambiguous. Both texts are also dated eighty years later than the events, which took place during the reigns of Sigfred and Godfred. On the other hand, a number of spectacular constructions may be dated to the 8th and 9th century: the founding of the first town, Ribe, ca. 700 – 710; the later foundation of Haithabu ca. 800; the existence of impressive palatial compounds at Erritsø, Tissø, Lejre and elsewhere. The reconstruction of an advanced wall, Danevirke, along the border between Denmark and Saxony; the early naval attacks on the Carolingian Empire involving an impressive fleet. All this evidence indicates the presence of a powerful regime.

On the other hand, this “kingdom” might not have been particularly well integrated. Thus, archaeology may have demonstrated a firm border between the material culture of the Abodrites and those of the Danes north of the Danevirke. However, archaeologists have also been able to register a set of distinct cultural differences inside this realm – pots, spindle-whorls, regional burial traditions etc.

Perhaps the realm in the 9th century was controlled by a small and very mobile band of elite warriors and magnates belonging to and perhaps married into a dynasty or clan of rulers at least counting back to the first recorded Danish King, Ongendus (Agantyr) mentioned c. 710 and even earlier? While the rest of the population oriented themselves inside more regional boundaries?

Two Name Hoards

What would such a group of elite warriors have looked like? How might it have been composed? After the record of the death of Godfred, we get a precious and unique glimpse of such a royal retinue in the Royal Frankish Annals.

Following the death of Godfred, we read in the Frankish chronicles that Hemming, who was the son of Godfred’s brother (Sigfred?) and the new King of the Danes made peace with the Emperor. Initially, this peace was “sworn on arms”. Later that spring, however, a diplomatic meeting was set up between two groups of twelve magnates, who met at the River Eider at an unknown location (Eiligen, Eligen, Heiligen); perhaps (and likely) Hollingstedt.

It seems fair to imagine the Franks considered the meeting as highly unusual. Not only did the compiler of Frankish chronicle report of the meeting as a piece of carefully balanced power-broking, he also took pain to remember the names of all the participants. Had it been one of the more usual diplomatic envoys meandering to Aachen, we might not have heard about it. The result – as it is – gives us a detailed glimpse of the kind of people each party sent to this meeting:

Among the Danish representatives, we first hear about two brothers of Hemming:

- Hankwin – (other versions: ancuuin, hacuuin, hancuuihc, hancuin, hancuum.) Probably: Haquinus, Haconus (Latin), from “Haki”, “Hakun” or “Hakon”, meaning “Giant” or (later) “Berserker”. The suffix –win means “friend” (“ven”)

- Angandeo (Agantyr) – brother of Hemming. (Other versions: agantheo, angaseo, agandeo, acgandeo.

Angantir, Angantyr (Lat. Anganterus Anganturus). From Old High German: Angandeo, Anghanteus, Ongentheuw (Beowulf). From: ongēan (against, opposite) þeōw (servant, slave). Ongendus is the name of a Danish king mentioned in Alcuin’s life of Willibrord. This Anglo-Saxon saint visited the Danish court as part of a missionary effort in ca. AD 710. Presumably, Willibrord met with an Ongendus at this time. It is assumed that the appearance of another Ongendus listed as a brother of Hemming, indicates the name was part of the hoard of “royal names” allotted to descendants of a Danish dynasty, which at this point may have been reaching at least a hundred years back.

Next follows a list of certain notable persons among the king’s men:

- Three men with the name of Osfrid, Old High German Ansifrid. The name is rare and is a composite of Ansi-/ansu, meaning áss or God and –fred, meaning peace. (other versions: Offrid, Osfred, Osfert)

– nicknamed Turdimulo. The Nickname is Swedish and refers to to the Alca Torda, the lesser Auk, a seabird

– son of Heiligen. (Other versions: eiligen, heligen, eligen). Meaning son of “Helghi”, compare Beowulf: Hālga, son of Healfdene. Helgi Hálfdanar was a legendary king in Lejre. Name of several legendary kings in Zealand.

– of Schonen, Sconaowe, sconaoue, sconatue, sconaouuae. Scania, the southeastern part of the Denemaerck, the frontier zone of the Danish realm at the end of the 9th century.

- Warstein (Other versions: Warsten, Warsteinus, Warsein. Anglo-Saxon: Wærstan, Waerstan or Werstane from Awæstan, meaning “From the West”, and as a metaphor: “to destroy, eat up”?

- Suomi – Glumi or Gluomi, mentioned in the Frankish Annals for AD 817 as the “custos Nordmannici limitis”. Glum means “terrible, dark, dangerous, noisy”.

- Urm – Orm, Wurm, Vorm, Worm; and Gorm (from GodwormR; compare to gothic Waúrms)

- Hebbi (Hebbin, Helbi). Ebbi, Ebbo, Ebbe, Æbbe. Widespread, perhaps an early loan of Eberhardus. Meaning “prince”.

- Aowin (Aduuin, acuvin, aouuim, auuin). The same name as “Hakon” – see above.

To conclude: In this name-hoard we meet one brother to the Danish King with a name indicating a connection back in time to (at least) the beginning of the 8th century. Another brother has a name which signals violence. The same name is found again in the group of magnates bearing names with “warrior” connotations – in all, three Osfreds, an Urm, a Glum, and an additional Hakon. As an outlier, we have a “prince” (Ebbe), and two with geographical linkages; one from the unspecified “west”, and one from Scania. Finally, it should be noted that one of the men may have had Swedish or Gotlandic affiliations, boasting of the nickname “Tordimulo”. To be noted should also the linkage to “old” royal names recurring in Beowulf. Did these names “mean” anything? Or were they just names? At least, the names boast of a long “history” with known royal connotations.

On the other hand, we encounter twelve Carolingian magnates, many of which belonged to the Emperor’s inner circle of select Frankish nobles and relatives

- Count Wala, son of Bernhard and grandson of Charles Martel – also known as Wala, cousin of Charlemagne

- Count Burchard – related to Charlemagne. Witnessed his testament

- Count Unrocus – married into the Carolingian family. Testified to the testament of Charlemagne

- Count Uodo (Eudes). Count of Orleans

- Count Meginhardus. Witnessed the testament of Charlemagne

- Count Bernhardus, Count of d’Autun, Septimanie and later Barcelona.

- Count Egbertus. Perhaps married to a sister of Wala? In command of the fortifications at Itzehoe on the river Elbe.

- Count Theoteri – no more is known

- Count Abo (Abbon). No more is known

- Count Osdag (Ostdag). No more is known

- Count Wigman. No more is known

At least five of these men were closely related to the Carolingian dynasty, while three acted as testators to the testament of Charlemagne.

Also, while the Danish deputation was led by two brothers of the King, the Frankish deputation was led by the cousin of the Emperor, Wala. Noteworthy is also the fact that the Danish contingent of men included the man, Gluomi, in charge of the Southern border, while the Carolingian deputation included the man in charge of the fortification on the north side of the River Elbe.

It seems the composition of the diplomatic mission was intensely argued during the planning period. Hence the idea to list the names in full. Both parties must have been aware of the need to ensure political parity and public confirmation of their status. Another noteworthy point is that Wala – with a Saxon mother – was known to be fluent in the Saxon way of life. Likely, he was able to speak directly to his Danish counterpart. Later, we hear more of the two Danes, Aowin and Hebbi, who were sent to Aachen as envoys, “bringing gifts and peace” (AD 814). Both parties would have had “culturally competent” envoys, which – it appears – were able to negotiate complex treatises among powers, which might boast of equally powerful yet culturally defined positions.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Collage of Coins. To the left coin from Dorestad minted by Louis the Pious 814 – 840 © Coinweek. Coin to the right from Ribe c. 820. © Sydvestjyske Museer.

SOURCES:

Einhardi vita Caroli Magni

Ed by O. Holder-Egger

MGH, SrG Hannover/Leipzi 1907

Annales regini Francorum 741 -829.

Ed. F. Kurze

MGH, SrG. Hannover/Leipzig

Poetae latini medii aevi: Poetae latini aevi Carolini, 1 – 4.

Ed. by E. Dümmler, L. Traube, P. von Winterfeld

K. Strecker. Berlin 1880 -1923

READ ALSO:

Zwischen Kooperation und Konfrontation: Dänemark und das Frankenreich

By Volker Helten

Springer Verlag 2011

Before They Were Vikings: Scandinavia and the Franks up to the Death of Louis the Pious

By Daniel Melleno

Berkely 2014

“Denemearc, “Tanmarkar But” and “Tanmaurk Ala”

By Niels Lund

In: People and Places in Northern Europe, 500 – 1600. Essays in honour of Peter Hayes Sawyer.

Boydell and Brewer 1991

Denemearc, Tanmaurk Ala, and Confinia Nordmannorum: The Annales Regni francorum and the origins of Denmark

By Paul Gazzoli

In: Viking and Medieval Scandinavia (2011), Vol 7, pp. 29 – 43

The Lands of Denemearce: Cultural Differences and Social Networks of the Viking Age in South Scandinavia

By Søren Sindbæk

Viking and Medieval Scandinavia, (2008) vol. 4, pp. 169-208.

Danmarks Gamle Personnavne 1-2

Ed. By Gunnar Knudsen, Marius Kristensen and Rikard Hornby

G.E.C. Gads Forlag 1936 – 48.

READ MORE: