What is best when considering Europe’s abandoned farmland? Should it be returned to more extensive – traditional and even Medieval – ways of sylvo-pastoral forms of cultivation? Or should it be rewilded with large grazers? Or left to its own devices? What might the outcome be regarding ecosystem services such as CO2 sequestration, biodiversity and rural welfare? New research probes the pros et cons of these different approaches.

In 2020, 157 mio. ha were used for agricultural production in Europe. To this, however, should be added over two mill ha at present “underutilised” Despite projections that 7%-15% were expected to be underutilised (abandoned) before 2030, the average percentage of farmed land appears to have remained on a constant level between 2005 – 2020. This figure, however, covers a multitude of variations in the different European countries, with Spain and Latvia (Valujeva 2022) mustering large tracts of land, which might be farmed but are not. Also, the structural shift from a landscape farmed by small traditional farmers to one farmed for monocultures by large agricultural cooperations getting paid in EU subsidies, in reality, probably should statistically place considerable tracts in the category “underutilised”. Whatever the facts and figures, there is no doubt that vast tracts of Europe are currently being abandoned.

From a policy point of view, the question is what the costs and benefits of this land abandonment will be depending on the different ways the land will be managed. This question is currently hotly debated inside Europe as well as in the various national governments.

What might be the positive and negative advantages of turning the land into extensively re-farmed use (sustainable agricultural activities)? Rewilded with natural grazers? Or just left to its own devices? These alternative responses to farmland abandonment lead to context-dependent impacts, potentially contributing to European Green Deal objectives for the environment and rural areas. Recently, this question has been explored to determine the benefits and risks associated with different management responses to abandonment within a thirty-year timeframe. The study was based on a meta-analysis.

Overall, the study found that regarding impact, the two types of management – Natural revegetation and rewilding came out on top concerning carbon sequestration and ecological integrity.

To this should be added the advantage of rewilding as to agrobiodiversity, also furthered by extensive Re-Farming. As multiple studies show, rewilding is the better option for forest fires. Concerning heritage, the extensive re-farming option “won out”.

By Catherine M.J. Fayet and Peter H. Verburg

In: Catena (2023) November 232

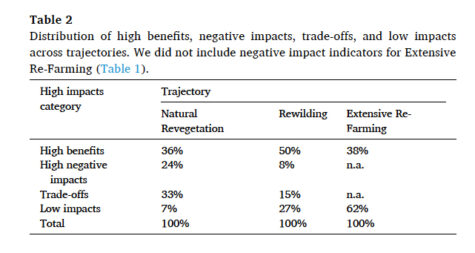

More precisely, Fayet and Verburg have studied the benefits of the precise option inside Europe and mapped these in terms of landscapes, finding that rewilding was the best or part of the best option in 39% of the locations. More precisely, rewilding offered 50% high benefits compared to Natural Revegetation, which scored only 36% high benefits together with 24% high negative impacts. Rewilding, on the other hand, scores only 8% high negative impacts. The authors conclude that Natural Revegetation was only the most preferred trajectory in a minority of locations (3%)

In conclusion, Fayet and Verburg write: “Informed decision-making about the benefits and trade-offs of different abandonment options is key to fostering the most suitable post-abandonment trajectory. Targeting resources and efforts to regions where benefits can be maximised for a specific trajectory aligns with the urgency of the climate and biodiversity crises. At the same time, aiming to maximise ecosystem benefits without considering stakeholders’ preferences, needs, land history, and societal relevance can lead to non-optimal and non-effective decisions,” they write.

Unfortunately, the assessment of carbon sequestration did not account for SOC, soil carbon, and the soil as a potential sink. Several studies have shown that above-ground-carbon is perhaps 25% lower in rewilded areas compared to restored areas with natural revegetation. However, these studies also show a definitively higher carbon accumulation in the soil, thus compensating for this deficit. Although further studies are needed, the results so far show an added value of at least 10-20% more carbon pr ha/year in actively rewilded areas than in passive rewilded areas (and much more than plantations). Simply put, the animals in rewilding projects trample down the carbon, flipping the advantage further towards active rewilding.

FEATURED IMAGE

Rewilding near lake Pape in Latvia. © Valeters Peins/ Dremastime.com/213469090

SOURCES:

Modelling opportunities of potential European abandoned farmland to contribute to environmental policy targets

By Catherine M.J. Fayet and Peter H. Verburg

In: Catena (2023) November 232

Abandoned farmland: Past failures or future opportunities for Europe’s Green Deal? A Baltic case-study

By Kristine Valujeva, Mariana Debernardini, Elizabeth K. Freed, Aleksejs Nipers, and Rogier P.O. Schulte

In: Environmental Science & Policy (2022) Vol 128, February pp 175-184

Rewilding abandoned farmland has greater sustainability benefits than afforestation

By Lanhui Wang, Pil Birkefeldt Møller Pedersen and Jens-Christian Svenning

In: npj Biodiversity (2023) volume 2, Article number: 5 (2023)