Backbred Aurochs have been released into the Greater Côa Valley for the first time. The herd will play a vital role in restoring grassland and woodland habitats in the rewilded landscape in Northern Portugal

In the 18th century, the aurochs – the wild cousins of our domesticated cattle – still roamed Moldavia. Never more than variety, they were just the wild version of the common species, the Bos Taurus. To claim that the last aurochs died out in 1627 in Mazovia in Poland is to insist that the species – the Bos or the common cattle – became extinct at that point.

Instead, as with wild horses, we might consider the different animals as belonging to one species comprising different varieties – from feral and semi-feral animals (such as the Exmoor pony) to full-blooded domesticated race-horses worth tens of millions of dollars.

What we should not subscribe to is the idea that they belong to different “races” or “breeds” – being the classification system, which only applies to domesticated breeds.

Nevertheless, a dedicated project aiming at “backbreeding” the Aurochs – the so-called Tauros Project – has worked on the presupposition that it is possible to “reconstruct” the B Bos primigenius, also known as the Aurochs. Recently, the release of a herd of these animals has been received with enthusiasm by people working in the rewilding movement. The question is, how should we understand this project?

The Tauros Project

Just as feral and semiferal varieties of horses are highly prized, and several projects work to back-breed the different varieties with the intact capabilities to live in the wild, the Dutch Tauros project (Stichting Tauros) has worked since 2009 to “backbreed” a modern-day version of the aurochs based on identifying the common “aurochs-genes” in the primitive European breeds still roaming wilder Europe.

The backbone of the projects consists of thirty ancient and more “primitive” breeds of the ordinary Bos Taurus, initially sequenced. In 2015, these results were compared to the successful sequencing of the first complete sequenced genome from a humerus bone from a British Aurochs, predating the first neolithic peasants. All-in-all, 38 breeds have now contributed to the project.

From this comparison, the scientists were able to identify seven Iberian breeds to be closest. Using those breeds and a few others, the scientists in the project worked to backbreed a type of cattle which phenotypically aligned with the extinct aurochs – primarily size, colour and the curvatures of the horns. The aim is 2030 to create a series of herds consisting of at least 150 animals, each living free and wild in rewilding areas all over Europe.

A flock of these backbred animals were recently released into the Greater Côa Valley in Portugal for the first time. More precisely, three Tauros bulls and 12 cows, four of which are pregnant, arrived in Portugal following their transportation from the Netherlands by Stichting Tauros (the Tauros Foundation). The animals were released into an enclosed paddock so that they could acclimate to their new environment, whilst the team monitored their health and behaviour for a couple of weeks before release. A few days ago, the animals were finally released into the free in a valley once home to the ancestor of the Tauros, the aurochs. Traces of the ancient bovine can still be found as part of prehistoric rock engravings within the Côa Valley, paying tribute to a long-standing cultural relationship with these animals.

Ecological role

As a result of their grazing and browsing habits, the newly released herd will contribute directly to creating varied and biodiverse habitats whilst removing dense vegetation and reducing the risk of devastating wildfires, which will allow native woodland to regenerate. With bulls weighing more than a ton, the animals will be able to set their mark seriously.

They also play a crucial role in the trophic food chain. The Côa Valley is already home to Iberian wolves and vultures, both of which will significantly benefit from the return of a large bovine. Whilst lesser-known scavenging invertebrates, birds and small mammals will also thrive due to their presence.

Restoring open plains grazing

Like much of Europe, Portugal has been experiencing the depopulation of rural communities for decades. People moved away from working the land, and vast numbers of grazing livestock were lost. Once open landscapes are now being covered by dense scrub vegetation or vast swathes of young forest, both poor in biodiversity and susceptible to wildfire.

“Large herbivores play an essential role in consuming biomass and creating more resilient landscapes to protect against wildfire,” explains Rewilding Portugal’s Head of Conservation, Sara Aliácar. “They will also be excellent at spreading seeds to help restore the habitats that have already been lost to fires, improving spaces for wildlife.”

The long-horned Tauros are entirely self-sufficient, requiring no further supplementation post-release. As they free-roam, they can also innately defend themselves from predation. As the animals restore the landscape, opportunities for local people will increase too.

Every summer, fires threaten Portugal’s forested areas. Grazing and trampling remove excess combustible material and lowers the risk of wildfires. Also, the large grazers will contribute to the future carbon sequestration needed to fulfil the climate goal of the Paris Convention.

The Tauros are not alone in their restorative role. They will join some of the 25 native-breed Sorraia horses Rewilding Portugal and partners have already released. A herd of 13 horses free-roam the northern part of the Ermo das Águias region, whilst the Tauros have been released in the south. The team look forward to the two species meeting and grazing the land together, just as their wild ancestors would have done.

The benefits of introducing semi-wild herbivores to these regions are already apparent. Wilder, naturally-grazed landscapes are now showing the early signs of becoming a nature-rich mosaic of biodiverse habitats.

“This is the first release in Portugal, and we plan to introduce Tauros to more areas within the Greater Côa Valley as we continue to improve connectivity,” says Deli Saavedra, Head of Landscapes for Rewilding Europe.

The releases will help to realise the rewilding vision for the area, with the Rewilding Portugal team and local partners now working to strengthen an important 120,000-hectare ecological corridor between the Douro region in the north and the Malcata region in the south. Their efforts are supported by a grant from the Endangered Landscapes Programme.

The Ancient Animal – the Bos Primigenius

So, what is the modern-day Taurus? To answer, we have to uncover the story of the wild aurochs, which roamed unhindered from China to the British Isles for several millions of years until 14.000 years ago. During this period, the great Eurasian Steppe was covered in temperate open forests alternating with steppe landscapes. The natural range would have shifted with the climate between glacial and interglacial periods.

The earliest archaeological evidence for the domestication of the aurochs dates back to the Middle East ca. 9000 BC. At the same time, the first domesticated cattle in Europe were archaeologically documented in the seventh millennium BC in Spain. This domesticated bovid was, perhaps, imported via the Donau and the Mediterranean. The Balkan Buša breed may genetically represent this early cattle, while the semi-feral Maremma in Tuscany may have Etruscan and earlier roots.

Until recently, scientists believed that the aurochs mainly lived in forests with closed canopies preferring riverine landscapes. New evidence suggests that the animals were always grass-eating animals moving effortlessly through the more or less open forested landscapes covering the Eurasian steppes. Ultimately, this preference for open forests and grassland led to a conflicted situation or “end-game” between the early Neolithic peasants and their domestic flocks.

A study from the submerged site at Neustadt in the Bay of Lübeck tells part of the story. The site was excavated in 2000-2006, and thousands of shards, faunal remains, plant and macrofossil remains, and flint artefacts were uncovered. Also, analysis of lipid residue of charred food crusts in Ertebølle pointed-based and Funnel Beaker pottery was studied to determine the shift from late foragers to early farmers in the settlement. The site was settled for over 600 years between 4400 and 3800 BC and fell within the transition phase.

The faunal remains comprised 12,693 bones, with a third identified at the species level. Of the 26 species in the material, the harp seal was the most common (14%), followed by wild boars (11%) and aurochs (10%). Red and rode deer, harbour porpoises and water voles played minor roles. The percentages are based on MNI – the minimal number of individuals.

Interestingly, domesticated cattle and sheep or goats comprised only 2% of the assemblage. Radiocarbon dates of the domestic cattle – identified with aDNA – dates it to ca. 3950 BC (4226-3705), the timespan generally accepted as the period when the early Funnel Beaker People migrated to Europe (c. 4300) to emerge in modern-day Northern Germany c. 4100-3950 BC. The study, however, shows that domesticated cattle played an insignificant role during the transition period compared to the continued hunting for large mammals, including the aurochs in the oak-dominated forests and open grasslands of the period.

In terms of size, the Aurochs differed from cattle. The bull might weigh over a tonne and feature shorter trunks and longer legs. Elongated heads and impressive horns might reach 120 cm in length and were black, while cows were smaller and had reddish brown coats. Descriptions indicate the animal was swift and agile. In terms of temperament, it could become hot-tempered and aggressive when confronted.

Interbreeding

From: Archaeologische Geseelschaft 1890. June, p. 104

One of the challenges identifying aurochs and domesticated cattle in archaeological assemblages is the wide variety of sizes among individuals of the two biological varieties. Due to an overlap of sizes, a clear distinction is not often possible. Although part of the domestication process was breeding smaller dairy cattle, the Aurochs cow might be just as small as a domestic bull, making the identification complicated without aDNA. Also, during the transition period (c. 4100 – 3900 BC), climatic and geological shifts caused a significant rise in sea levels producing the archipelago in the Baltic and Kattegat creating genetically isolated populations of Aurochs, perhaps causing a series of phenotypical changes in terms of size.

Part of the domestication process in Europe was the breeding of more miniature cattle. Scientists have suggested that the smaller sizes reflected poorer diets offered to animals, which were kept close to the peasant farm for reasons of their manure. However, studies of the bone- assemblages in Northern Europe show another trend. Here, domesticated cattle appeared in the early phase to increase body size. This fits well with the conclusion that occasionally – and perhaps intentionally – interbreeding (introgression) took place.

Genetically, ancient cattle all over Europe have been shown to carry mitochondrial DNA from both the Middle Eastern pool and the Aurochs, indicating that introgression from wild aurochs into domestic flocks took place and was probably more widespread and frequent than hitherto expected. It appears purposeful restocking with wild aurochs was relatively common among herders in peripheries such as Northern Europe, Switzerland, and perhaps Spain.

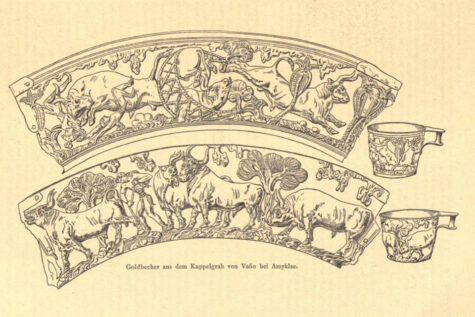

Thus, casual interbreeding between aurochs and domesticated cattle continued in Antiquity in the same way as interbreeding of feral, semi-feral and domestic horses was common. This might occur as a happenstance when wild stallions or bulls recruited domesticated mares or cows to join their flocks. But it was definitely also intentionally practised, as witnessed by the famous cups from the 6th century BC Vafio in Greece, which show us in great detail how a capture might be organised – mildly by luring the bull to discover a willing cow. Or more wildly, by capturing the ferocious bulls with nets. This evidence aligns with the famous description of the Aurochs by Caesar:

“There is a third kind, consisting of animals called URI. These are a little below the elephant’s in size and have the appearance, colour, and shape of a bull. Their strength and speed are extraordinary; they spare neither man nor wild beast which they have espied. With much effort, the Germans hound them into pits and kill them. The young men harden themselves with this exercise and practice this kind of hunting. Those who have slain the greatest number of them and can produce their horns publicly to serve as evidence receive great praise. But not even when taken very young can the animals be rendered familiar to men and tamed. The size, shape, and appearance of their horns differ much from the horns of our oxen. These they anxiously seek after, to bind the tips with silver that they may be used as cups at their most sumptuous entertainments.”

From: Caesar De Bello Gallico, chapter XXVIII

Inbreeding or backbreeding?

After Glykou 2016. © By kind permission Aikatarian Glykou

Scientific studies and historical sources thus document that both interbreeding and inbreeding continued to take place up until the extinction of the last herd at Jaktorow in 1627. We may therefore ask whether the backbreeding of the Tauros makes sense. Might we not be just as satisfied with the present-day descendants devolved through interbreeding programmes of all sorts? And – cutting to the chase – is this what the backbreeding programme of the Tauros and other similar programmes consist of?

Granted, the auroch was a larger and perhaps more ferocious animal with a different appearance and colour than the domesticated ox. However, wilder and more primitive breeds continue to live as descendants of animals intermixing in medieval and premodern landscapes. And yes, we do need megafauna to help the ecological restitution of our landscapes. But do we need animals created as part of an intentional backbreeding programme?

We may well ask: Does the modern backbreeding of the Stichting Tauros make more sense than the programme the zoo directors Heinz and Lutz Heck instigated in the 30s? A backbreeding programme, which in the best Nazi tradition of racial thinking, aimed to recreate the “Ur Tiere” of the Germanic youngsters hunting for horns in Caesar’s vignette. An endeavour which resulted in the Heck cattle and, ultimately, should not be mistaken for the Tauros backboned by the Stichtung.

Further, what will happen if any of these carefully bred new/old varieties are let loose for real in wilder Europe and begin to create an admixture with local cattle or even the European bison or visits? The latter animals are already genetically documented to be mixed with cattle, likely reflecting the Aurochs and Bison intermingling in the large great East European wildernesses in Late Medieval Europe. Currently, the wilderness at Bornholm housing a celebrated herd of European bison has been obliged not to include wild or semi-feral cattle in the planned National Nature Park there, as “they might mingle”.

Also, the backbreeders of the Tauros programme seem not to have gone the whole way, discarding some of the more likely candidates for breeding, the temperamental fighting bulls from Spain. This restraint has been called for to initally avoid a popular revolt when letting the new Tauros loose. As opposed to this, the descendants of the Heck cattle (curiously know as the Taurus) are known to be less “friendly”. Thus, a few years ago, these considerations led the managers at Lille Vildmose to move their Heck Cattle from a small forest close to the beach, where people walkws by, and further inland to a rather dreary enclosure. Another argument was the cost.

To some extent, the question of backbreeding has to be debated in the same manner as reenactments and archaeological reconstructions. Indeed, we might gain substantial new knowledge about the wild ancestors of our domesticated subspecies by tweaking the genes of their descendants. On the other hand, if trophic rewilding ultimately means letting nature run its course while building robust ecosystems, we need megafauna to ambush our well-ordered mindsets and traditional rules for nature planning. Thus, we might just let loose the more primitive descendants of the Bos Primigenius and the Bos Taurus to mingle as evolution would dictate.

The situation resembles the challenge posed to curators left with a crumbling medieval ruin on the brink of falling apart due to wind and weather. Do we rebuild the ruin, creating a pastiche? Or do we try to protect the ruined sites from our imagination and phantasies?

Karen Schousboe

FEATURED PHOTO:

Tauros set free in the Coa Valley © Rewilding Portugal and Claudio Noy 2023

NOTE:

The spelling of Tauros of Taurus is not used interchangeably here. The Greek spelling refers to the modern Dutch project of resurrecting the aurochs, while the Latin refers to the old project, also known as the Heck Cattle project.

BASED ON:

press release from Rewilding Europe: First Tauros release in the Greater Côa Valley will boost natural grazing

Rewilding Europe 2023

Stichting Taurus: Aurochs Genetics: A Cornerstone of biodiversity.

Rewilding Europe 2015.

SOURCES:

On the Origin of Cattle: How Aurochs Became Cattle and Colonized the World

By Paolo Ajmone-Marsan, José Fernando Garcia, Johannes A. Lenstra and the Globaldiv Consortium.

In: Evolutionary Anthropology (2010) vol 19 pp 148-157

Genome sequencing of the extinct Eurasian wild aurochs, Bos primigenius, illuminates the phylogeography and evolution of cattle

By Stephen D E Park, David A. Magee, Paul A. McGettigan, Matthew D. Teasdale, Ceiridwen J. Edwards, Amanda J. Lohan, Alison Murphy, Martin Braud, Mark T. Donoghue, Yuan Liu, Andrew T. Chamberlain, Kévin Rue-Albrecht, Steven Schroeder, Charles Spillane, Shuaishuai Tai, Daniel G. Bradley, Tad S. Sonstegard, Brendan J. Loftus & David E. MacHugh

In: Genome Biology 82015) Vol 16 mo 234

Cattle husbandry and aurochs hunting in the Neolithic of northern Central Europe and southern Scandinavia. A statistical approach to distinguish between domestic and wild forms

By Ulrich Schmölcke, Daniel Groß

In International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2021) vol 31 no 1,

Transitions During Neolithisation Processes in Southern Scandinavia. New Insights from Faunal Remains and Pottery from the Site Neustadt LA 156 in Northern Germany.

By Aikaterini Glykou

In: Past Societies. Human Development in Landscapes. Ed by Johannes Müller and Andrea Ricci.

Sidestone Press 2020.

The history of the European aurochs (Bos primigenius) from the Middle Pleistocene to its extinction: an archaeological investigation of its evolution, morphological variability and response to human exploitation

By Elizabeth Wright

PhD, Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield. 2013

Investigating cattle husbandry in the Swiss Late Neolithic using different scales of temporal precision: potential early evidence for deliberate livestock “improvement” in Europe

By Elizabeth Wright

In: Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2021) volume 13, Article number: 36

Ancient DNA analysis of Scandinavian medieval drinking horns and the horn of the last aurochs bull. 2018

Maiken Hemme Bro-Jørgensen, Christian Carøe, Filipe G. Vieira, Sofia Nestor, Ann Hallström, Kristian M. Gregersen, Vivian Etting, M. Thomas P. Gilbert, Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding,

In: Journal of Archaeological Science (2018) Vol 99, pp 47-54

READ ALSO: