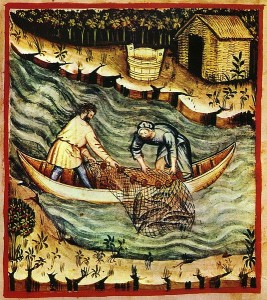

Fish was definitely food for fasting. But not raw fish, which was deemed unhealthy, raw and uncivilized

Bad is that land and not well graced, A wilderness it is and waste: Skywards its crags and peaks do soar, It snows and hails for evermore; A fearful and repulsive place. Its men both weird and wild of face. No peace they know, no quarter give. They pay no heed to how they live: They feed on fish, their meat is raw, Like wolves they tear at it and paw… They dress in untanned hides as well As if they come straight out of Hell. [1]

Bad is that land and not well graced, A wilderness it is and waste: Skywards its crags and peaks do soar, It snows and hails for evermore; A fearful and repulsive place. Its men both weird and wild of face. No peace they know, no quarter give. They pay no heed to how they live: They feed on fish, their meat is raw, Like wolves they tear at it and paw… They dress in untanned hides as well As if they come straight out of Hell. [1]

Fish deteriorates very quickly. Therefore, the best way to eat it is grilled on the beach (John 21: 9) or even raw, freshly fished. Even today, Danish connoisseurs may be seen walking the mussel banks in wintertime, enjoying raw mussels and oysters on the spot.

Jesus was of course the fisherman par excellence and the Apostles (his crew); and early on Jesus became symbolized by the sign of a fish (Ikhthus). Nevertheless the eating of fish gradually attained a somewhat dubious character after the year 1000, when the pattern of fish consumption changed dramatically. Fish was good – but not all fish and not everywhere.

Anselm of Canterbury

One illustration of this comes from William of Malmesbury (ca. 1095–1143), when he recalled his great contemporary, the Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury (1033 –1109):

“Right up to the end of Anselm’s life his bodily strength and fervent piety continued unimpaired… he surpassed all the men we have ever seen in wisdom and piety. Sin was completely foreign to him. He once told a close friend of mine, whom I believe implicitly, that after he became a monk, he had never been so goaded by anger as to hurl an insult at anybody – well, this had happened to him just once. He had never except once spoken a word, of which the memory made his conscience sore. At supper one day, realizing that he had eaten raw herring, he struck his breast and lamented his sin, that against the rule he had eaten raw flesh. But Eadmer, who was sitting next to him, said that the salt had drawn out the rawness of the herring. Anselm replied: “You have cured me of being tormented by the memory of my sin”. [2]

Whether the fish, Anselm partook of, was pickled or just salted, we do not know. But even today it is a great delicatessen to eat “raw herrings” at the harbour at Rotterdam and the cook in the monastery may have had the opportunity to serve something less distasteful as herring directly from the barrel. And apparently got slapped for it!

Raw fish was simply uncivilized – probably considered either a sign of gluttony, because the partaker have not waited to cook the fish; or it was considered a delicatessen in view of the challenges of getting fresh fish on the table.

Fresh fish could be transported no more than up to 150 km in barrels; accordingly fresh fish was either a luxurious delicatessen or something, which should be regarded as gifted by God and eaten on the spot. Proper fish was dried, salted, smoked (or nowadays frozen), in which case it turned into a proper communal food.

Bernard of Clairvaux

Just about the same time, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 -1153) reflected on the proper way of fasting. Born a younger son into a family of minor nobility in Burgundy, Bernard entered Cîteaux as a young man in 1112. Gifted as a charismatic person he devoted his life to reforming the monastic movement, which at that time overwhelmingly was characterised by the praxis of the Benedictines at Cluny. One issue, which especially enflamed Bernard had to do with food. In a number of letters and writings it is possible to follow the harsh critique, which was pointed at the sybarites down the road. One of the central texts is the Apologia for Abbot William. In this he writes about how course after course is brought in a mealtimes. And because the Benedictines would not break the taboo and eat meat, these dishes were doubled and made from fish of all sorts of varieties. “You only have to begin sampling the second dish to imagine that you have never tasted fish before”, he wrote. Bernard was especially critical about the relishes, condiments and sauces, which accompanied these fish-dishes. He felt that all this was too alluring to the senses and promoted an appetite above and beyond what was proper. Roast fish, boiled fish, stuffed fish, fried fish… no doubt the best way to govern the appetite, was to stay away from it all. Even later the Cistercians continued to abstain from fish, eggs, milk, cheese or white bread, let alone meat or lard, as was claimed by Jacobus de Vitry a generation later. In the end, of course, Bernard was correct; fish was at that time rapidly becoming the luxurious alternative to meat, which the rules of fasting during Advent, Lent and specific weekly days came to stipulate as offensive for not only clerics but also lay persons. As such certain fish became a sign of wealth sought by the elites at court, in the growing towns or at the magnificent new monasteries. Also the procurement of fish became rapidly more complicated in a world with a growing population which further seems to have acquired the taste for a new and refined, religiously inspired cuisine. Sign System As a sign system it was quite complicated. Topping the list were whales, porcupines and seals. Next on the list was the near extinct sturgeon followed by tuna, salmon, swordfish. Further down the list were pike, carps, bream and to a lesser extent eels supplemented by large white (fresh) fish like cod. At the bottom of the social pyramid the fish became smaller or were either salted or dried. Five grids seems to characterise this sign system, which was used to create social distinctions in the later Middle Ages

Raw: Cooked

Scarce : Common

Large : Small

Fresh : Conserved

Whole : Parts

However this sign system could be manipulated. For instance “whole fish” were definitely elite-food, although certain parts could be considered special delicacies, like the cheeks of cod or monkfish.

Pietro Querini

Further, the system would be suspended at the frontiers of Europe where fish was simply part of the daily staple diet. In 1431 an Italian, Pietro Querini, shipwrecked off the coast off Røst at Lofoten. Afterwards he and his men spent nearly 4 months living alone on the coast. First they had to live off mussels but at a later stage they found a whale on the coast. A little later, the locals from a nearby island saved them. The staple food all that summer, however, turned out to be something of a strange culinary experience for the Italiens: Stockfish and salted flaunders. At Lofoten nothing could grow and for two months they ate nothing but “butter, fish and some meat” plus fresh milk, he tells us. [3]

NOTES:

[1] From: The Owl and the Nightingale ca. 1189 – 1216, lines 999 – 1014, translated by Ian Short. In: A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Ed. By Christopher Harper-Bill and Elisabeth van Houts. Boydell & Brewer 2007. [2] From: William of Malmesbury: The Deeds of the Bishops of England. 65 (1109). Edited and translated by David Prest Boydell Press 2002. [3] From: Pietro Querini, Nicolò De Michiele, Cristofalo Fioravante (ed.by Paolo Nelli). Il naufragio della Querina. Veneziani nel circolo polare artico, 2007.

READ MORE:

A Hermit’s Cookbook. Monks, Food and Fasting in the Middle Ages. By Andrew Jotiscky. Continuum 2011 Food and Faith in Christian Culture By Ken Albala and Trudy Eden (eds) Columbia University Press 2011 In Series: Arts and Traditions of the Table: Perspectives on Culinary History Food in Medieval England. Diet and Nutrition. By C.M. Woolgar, D. Serjeantson and T. Waldron T., eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

ENJOY:

Recipe for Raw Herrings Gut and filet half a kilo fresh herrings and freeze them for 48 hours in order to kill any parasites. Mix 1 dl salt and 1 dl sugar and rub it into the filets. Leave them covered in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Then rinse them under running, cold water and peal off the skin. Place them flat on a plate and sprinkle them with lots of fresh dill. Serve with boiled potatoes, butter and salt. (Recipe picked up in the harbour of Rotterdam in the 1930s)