Kujataa – Southern Greenland – holds the ruins of the Norse Settlements and their Inuit neighbours. Today, UNESCO inscribed the old farming landscape as World Heritage.

“The overall landscape of pastures, fields, ruins and present-day buildings is an outstanding example of human settlement and land use in the Arctic, which is representative of a unique farming culture. Kujataa constitutes the first European settlement in the New World and the earliest introduction of farming to the Arctic. The resulting cultural landscape, shaped by grazing both in medieval and modern times, is composed of grassy slopes and willow copses and characterised by a low settlement density with isolated farmsteads surrounded by cultivated fields. The landscape of Kujataa represents the exceptionally comprehensive preservation of a Northern European medieval culture. The five component parts contain the full range of remains relating to Norse Greenlandic culture dating from the 10th to the 15th century AD, with complete examples of monumental architecture as well as key sites illustrative of the adaptation of Inuit to a Farming way of life from the 18th century onwards.” (From the official nomination).

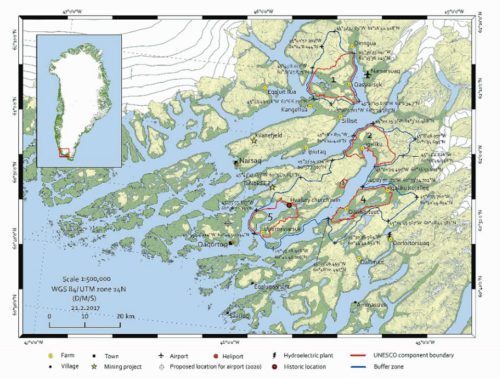

Kujataa is the sub-arctic farming landscape located in the south-western part of Greenland and covering app. 350 km2. Its green and lush character prompted the first Norse settlers to name the island Greenland; in Kalaallisut, is called Kalaallisut Nunaat, ”Land of the Kalaallit. It bears witness to thousand of years of hunters and gatherers exploiting the landscape in numerous ways. Later, at the end of the 10th century, Norse people began to arrive by ship to more than just trade furs and walrus ivory with the Inuits, but to settle.

The story is that Erik the Red in 985 sailed west from Iceland. With his ships, he rounded the southern tip of the Island and settled in the lush meadows in what he called Eystribyggð or the Eastern Settlement. Later, he sailed further west and explored “Vinland”, present day Newfoundland.

It was however at Brattahlíð, located at the head of the Tunulliarfik Fjord near present-day Narsarsuaq, where he built the first farm, a chapel and later a church. This initial settlement fostered numerous others. Based here, the Viking settlers continued to farm the land as well as explore the hunting and fishing of the region until their descendants left in the first part of the 15th century. Excavations of farms have shown that it was normal to have at least one or two cows, sheep, goats and horses. Later – at least from the 13th century – the Thule Inuits moved to the area.

Ivory

Especially the hunt for walrus and its ivory was an essential element in the economy; perhaps even the most important reason why the settlements thrived. In 1327, 802 kg of ivory tusks thus represented the value of 780 cows or dried fish. No wonder the Norse settlers were continuously in contact with merchants and sailing-ships eager to furnish the farmers with supplies of a diverse kind plus craftsmen like for instance the stonemasons, which built the cathedral at Gardar. Studies of the excavated clothes from Herjolfsnæs have demonstrated that people were quite conscious about fashions reigning further south.

he Norse Greenlandic population may have 2,000-3,000 people andwas govened with an established ecclesiastical as well as secular administration – a thing – centered at Gardar.

Last mentioned in in the written sources in the mid 15th century, archaeologists and historians have debated why the abandonment of the settlements apparently took place.

The general explanation is that the income from ivory became less and less stable as Europe from the beginning of the 15th century was flooded with walrus from Russia and Elephant tusks from Africa. At the same time, the Little Ice Age and its colder weather made it a steadily more risky business to engage in trade with the Norse in Greenland. Also, studies of their diet have shown that it became more and more supplemented with seal, whale and fish. It is now believed that people slowly immigrated to warmer and more favourable climates. The people did not so much die out. They simply packed up their valuables and left for good.

Later in the 18th century, Inuit farmers began to explore the possibilities of the landscape anew, and today, the region is famous for its sub-arctic farming, which represents its primary commercial activity. With sheep husbandry, small cattle herds and arable agriculture/ fodder production the primary focus is on livestock farming. But vegetables – potatoes and roots – are also widely praised because of their tasty character. For both the Norse settlers and the Inuits, though, survival was always dependent on supplementary hunting and fishing.

The landscape thus holds remains of both the Norse settlers and the hunter gatherers of the Thule Inuits. Of primary importance are the ruins at Sissarluttoq (Norse ruins), Qaqortukulooq/Upernaviarsuq (Hvalsey Church), Qassiarsuk (Brattahlíð) and Igaliku (the Episcopal centre of Gardar), which all witness to the Norse heritage.

The landscape, however, holds numerous other ruins not yet excavated, and one of the advantages of the inscription as World Heritage is that local communities now have the backing for a more rigorous effort to preserve and document the ruins and archaeological remains of the landscape. A particular challenge is to safeguard the landscape from too invasive agricultural practices fostered by the possibilities following climate change. Another problem is that Greenland lacks professional archaeologists as well as tourism experts, who can supply the necessary care for the precious landscape while at the same time secure a sustainable development of the tourism industry.

Hopefully the new prestigious inscription by UNESCO will further the effort to protect and guard the landscape.

SOURCES:

ICOMOS. 2017 Evaluations of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties

IUCN Evaluations of Nominations of Natural and Mixed Properties to the World Heritage List

Kujataa. A subarctic farming landscape in Greenland. Management plan 2016 -2020

READ MORE:

Norse Greenland Dietary Economy ca. AD 980–ca. AD 1450. By Jetter Arneborg et al.

In: Journal of the North Atlantic 2012, p. 1 – 31

The Lost Norse.

By Eli Kintish

Science 11. Dec. 216, Vol 354, No. 6313