In 1977 the Sarcophagus of Chrodoara was discovered in the church in Amay. The stone-carvings on the slab are widely recognised as universally beautiful. But what was her story?

As with any Merovingian saint, the story of the life of Chrodoara is fraught with uncertainties. Her name indicates she belonged to a clan peopled by persons named Chrodar, Chrodeber, Chrodegar, Chrodoald or Chrodobald. This clan – the Chrodoinides – was very active in the upper Meuse and responsible for the foundation of the Abbey at Wissembourg and the monasteries at Tholey and Beaulieu en Argonne. Of these, the Abbey at Tholey was founded by Adalgisel-Grimo, who undoubtedly belonged to this kin group. His last will and testament dated to 634 is one of the few, which have been preserved. In this he mentions some wineries from which he derived usufruct, which belonged to the church at Amay, “where my aunt is interred”. This church was dedicated to St. Ode, whose remains were kept in a reliquary until the Revolution.

Then, in 1977, a tomb was sensationally discovered in the crypt of the church in Amay, three meters below the choir, revealing a magnificent stone slab with Chrodoara depicted as an abbess holding her staff and scholars soon agreed that Chrodoara undoubtedly was this aunt.

From her 13th century vita a few more particulars may be wrought. According to this Chrodoara had married a Frankish duke called Bodegisel, known from the writings of Gregory of Tours and a poem of Venatius Fortunatus. At his death, she presumably took a vow of chastity and settled in the valley of Meuse at Amay, where she founded first a chapel, and later an abbey dedicated to St. George. In 730 her cult as rekindled as part of the propaganda initiated by Charles Martel. According to later stories, Chrodoara had been the great-grandmother of Plectrudis married to Pippin of Herstal. She seems to have represented a powerful clan with which Charles Martel had to come to terms, even as he conquered and annexed their land. Chrodoara was later known as St. Ode and continued to be remembered under this name at Amay.

Usually, the tomb can be admired through a glass window in the floor at the exact location, where it was found.

The tomb is made of limestone and engraved with two inscriptions identifying the deceased.[1] The lid is worked on all four sides. The carvings on the sides show interlacing vine foliage, comparable to other such tombs found in Dunes Hypogeum in the region of Poitiers. These, however are not decorated with the exquisite carvings which embellish the lid of the coffin of Chrodoara.

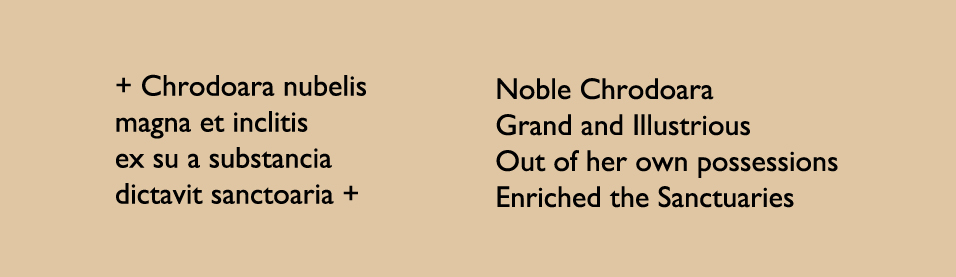

One of the inscriptions carefully identifies the woman on the lid as St. Chrodoara, the other more complex can be deciphered like this:

The tomb is exceptional. Even though numerous Merovingian moulded plaster sarcophagi may be found, which have been decorated with exquisite carvings of crosses, animals and Christian symbols, most show interlace decoration (both animal and plain) or other geometric designs. Nearly all of them a void of human renderings or portraits. Not so, the lid of the tomb of Chrodoara, which shows her looking out on us with a friendly and comforting smile.

The date of the sarcophagus is controversial. Art historians debate whether it can be dated early in the mid 7th century or is later, perhaps to the beginning of her cult around 730. However, the designation of saint may not be used to date the sarchofagus as such title were used just to indicate a person who had renounced the world in order to live in a religious community [2].

13th century Reliquary

In the mid 13th century, her relics were translated into a reliquary, which may still be found in the Church of Amay. This Shrine measures 104 x 44 x 59 cm and is dated to 1235 -1250. It carries low reliefs in silver presenting the stories of St. Oda and St. Georges. At the same time a new version of her vita – Beattisime Odae Viduae – was edited for a more “modern” purpose.

One side of the lid is dedicated to St. Georges, while the other shows St. Oda.

In the first plaque, she is shown washing the feet of a pilgrim, showing off three scallops on his bag. This is one of the first times where the symbol is linked with the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and St. Jacob. On the next plaque she is taking part in a mass, while the last one probably shows her death. On the other side, the plaques tell the story of St. George killing the dragon flanking the crucifixion of Christ. In the third plaque the saint is seen being decapitated by Diocletian, because he would not recant his Christian faith. This is one of the early artistic renderings of the story.

Probably this shrine substituted an older of which a fragment may be preserved in The British Museum in London. The gable-end dated 1170 depicts St. Oda between two figures representing Religion and Charity inside an architectural frame decorated with copper plaques and crystals. This is bordered with two frames of which the outer is adorned with enamelled plaques and further crystals, while the inner shows alternating copper plaques and eight horn-covered compartments containing relics.

In the cloisters next to the collegiate church a splendid exhibition shows the later shrine, but also the archaeological remains found on the banks of the river and in nearby cemeteries – glass, ceramics, stone, bronzes and iron-utensils from the 4th to the 8th centuries.

Amay is found on the west side of the river Meuse, between Liège and Huy. The town of Amay was located directly on the old Roman road linking Tongres and Arlon.

NOTES:

[1] Le sarcopharge de Sancta Chrodoara à Saint-Georges d’Amay. Essai d’interprétation d’une découverte exceptionnelle [article]

By Jacques Stiennon

In: Comptes rendus de L’Académie des inscriptions et Belle-Lettres (1979) Vol. 123, No 1, pp. 10 – 31.

[2] Une grande dame, Chrodoara d’Amay

By Nancy Gauthier. In: Antiquité Tardive. Revue Internationale d’Histoire et d’Archéologie (IVe-VIIe siècle) (1993), Vol 2. pp. 251-261

FEATURED PHOTO:

Sarchophagos of Chrodoara. Source: Wikipedia

SOURCE:

Le sarcopharge de Sancta Chrodoara à Saint-Georges d’Amay. Essai d’interprétation d’une découverte exceptionnelle

By Jacques Stiennon

In: Comptes rendus de L’Académie des inscriptions et Belle-Lettres (1979) Vol. 123, No 1, pp. 10 – 31.

VISIT:

Musée Communal d’Archéologie et d’Art religieux

Place Sainte Ode, 2c

B-4540 Amay

READ MORE:

Le Sarchophage de Sancta Chrodoara en L’église collégiale Saint-Georges d’Amay.

Bulletin du cercle Archaéologique. Amai, Hesbaye Condroz, 1977