The classic understanding of the history behind the castle-building on hilltops in the medieval Mediterranean landscape – the incastellamento or incastellation – has recently shifted. The reason is knowledge arduously gathered by archaeologists since the 80s

In 1973 the French historian Pierre Toubert published a study of the landscape in the hills behind Rome in the Sabinian mountains in the 10th to 12th centuries. In this study, he first launched the hypothesis that the ubiquitous hilltop villages in Italy were formed ex novo around a nucleus of small towers or “roccas” in this period. Later known as the Toubert-thesis of incastellamento, the castles complete with villages became to be understood as the products of lordly initiatives. As such, they signalled a movement from a more dispersed – and less well-controlled landscape – towards a dominated and controlled world. Where castles in northern Europe were built on the periphery of villages, they tended in a southern European context to be built together with or inside a village.

These small town-like settlements with houses crammed into narrow streets took many forms, depending on whether the castles were built in the centre or – as more often – above on the summit. Often equipped with churches (chapels), deep cisterns, and proto-industrial workshops, these fortified hilltops were part of a significant movement to fortify the landscape. Common to these were their character as venues for agricultural colonisation and expansion bankrolled by lords intent on exploiting the peasants while providing protection for them (and their other investments) against marauders, robbers, and invasions.

The early heartlands for this movement were Province and Italy, but Spain was also enrolled in this new fashion dotting landscapes with castles and subordinated settlements.

Rocca San Silvestro

Initially, one of the best studied of these types of settlements was the Rocca San Silvestro in Tuscany, situated behind the Campiglio Marittima, and constructed around ancient mines exploited by the Etruscans for copper, silver and lead. However, the first signs of a more permanent medieval exploitation stem from the late 10th century, when the count of Gherardesca planned the new settlement on top of the Rocca.

At the centre, he built a walled, noble residence surrounded by quarters for soldiers and servants. To the east of this citadel was a church dedicated to St. Sylvester. In front of this was a cemetery, from which the archaeologists excavated the remains of c. 300 individuals. To the west and north, lay the workshops, where metals were recovered. Below this lay the houses and huts of the miners and their families, probably 200 – 300. Finally, a complete 400 m long wall fitted with towers defended the castle and its village. Today, the site lies in the middle of a museum park where experimental archaeology is also carried out.

Tuscany

Later, however, several micro-studies demonstrated that the classic Toubert–Model was much too inflexible. It appeared that the history of the settlements and landscapes often played out with a different chronology.

Later, however, several micro-studies demonstrated that the classic Toubert–Model was much too inflexible. It appeared that the history of the settlements and landscapes often played out with a different chronology.

According to this new model – the so-called Tuscany-model voiced by Riccardo Francovich, Marco Valenti and others – the landscapes in Northern and Central Italy witnessed a much more complex devolution: first, the population in the 5th to 6th centuries was severely depleted due to climate deterioration, plague and war. From the end of the 6th century and through to the 8th century, the remaining Roman villas were finally abandoned while the (few) remaining people sought to establish more nucleated settlements – often on higher ground – to avoid the ravages of flooding, land erosion and violence. Next phase consisted of a gradual organisation of these settlements led by seigniorial powers constructing the new 10th century castles. This does not imply that some fortified villages were not founded ex novo, but it does imply this was not necessarily the general case. According to a survey from 2008, of 41 castelli or hilltop villages studied in Tuscany, only a third was created from scaratch.

Systematic large-scale studies of settlements, villages, castles, and landscapes in Tuscany carried out during the last twenty years have led to this conclusion. In a recent overview, Valenti has counted evidence from excavations and studies of 49 castles, three fortified settlements, four isolated houses, five caves, 18 villas, 12 churches, and three open villages covering the whole period from pre-roman times to late medieval.

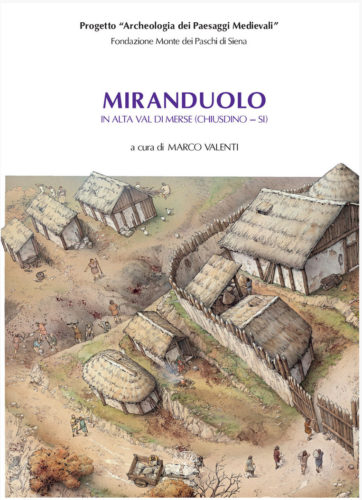

As part of these excavations, it has been demonstrated that the houses in these Early Medieval villages or settlements were built of perishable material. Only very rarely was stone used and finds show signs of social hierarchy was nearly absent. Parts of these settlements were filled with “Germanic” pit huts to which materials were readily available after the reforestation, which took place after Late Antiquity. Such pit or sunken huts (Grubenhäuser) were built on top of pits dug a metre into the ground and approximately eight four to eight metres in diameters; roofs were supported by posts. It is believed that the practical knowledge of how to built with stones virtually disappeared. Timber palisades often defended these villages or nuclei inhabited by peasant families; however, the social fabric in these villages seems to have been highly homogenous. Excavated fabric, pottery and studies of diets indicate that social heterogeneity was not the order of the day. Also, paleobothanical studies have shown that agriculture was diverse and basically oriented towards subsistence.

In the 8th century, however, these Tuscan villages became more “orderly”: to one end a more distinguished or elite space might be discerned, while at the other end ordinary families kept living as before. One such example can be found at Montarrenti (near Sovicille at Siena), which may have had two defensive timber palisades to defend the upper and lower zones. Sometime between 750 – 850, the upper zone was transformed into an elite space surrounded by a stone wall. The end of this process was the construction of an elite domus consisting of two towers and later a palatio in the 12th century.

In due time these privileged spaces also offered presented some more specialised production facilities – granaries, forges, kilns, grinding structures, special workhouses for butchering and baking, etc. To this would often be added a chapel or church. Archaeological evidence about the distribution and consumption of food has helped to understand the new socially heterogeneous landscape of the 10th century.

One as yet undecided question is what role churches and church buildings played in this process. A preliminary conclusion is that these early medieval villages used churches built to service several of them and that these more often than not were located in between in the settlements and further down in the valleys. Later, the castelli or hilltop villages from the 10th and 11th century were gradually fitted with private chapels, which may well have been used by the villagers too.

Again, though, the picture is muddled. From Lazio, we thus know of the early medieval construction of so-called domuscultae, papal houses and churches, which were constructed in the countryside. Later, however, also these were broken up to be restructured as castelli in the 10th -12th centuries.

Valmarecchia and Salerno

Another such micro-analysis, which has uncovered a multitude of stories behind the fortified hill-top villages is the surveys conducted by Daniele Sacco on the sub-region of the Valmarecchia (in the hinterland of Rimini on the east coast of Italy).

Finally, a study of the hinterland of Salerno should be mentioned. Here the Normans (11th – 12th centuries) were responsible for a widespread incastellamento, which was devised to control and subdue the local populace increasingly placed “sub dominio et defensione”. Incited by the widespread violence in the countryside these peasants donated their land to lords, whether ecclesiastical or secular, For this, they received the right to continue to farm their land typically based on sharecropping contracts. Supplemented with taxes, work and other obligations, conditions could and would be varied. However, as was the case with Valmarecchia, the fortified hilltop villages in the mountains behind Salerno did not represent new settlements. Typically, the castles were built in the midst or near existing population centres, thus not evidence of widespread population movements as Toubert initially argued.

Conclusion

To conclude: As should be expected the development of the Italian landscape took many forms and at different times according to local traditions and geographical conditions. However, a general summation leaves us with the picture characterised by distinct phases: at first, the Roman villas and latifundia combined with dispersed settlements fell into disuse and ruin. After this, people moved together in villages, some of which were erected on hill-tops. Later seigniorial power led to castles and fortifications being built into or next to these villages creating the fortified hill-top villages, which became the norm in the 10th to 12th centuries; and which may still be seen towering over the medieval landscape of Italy.

SOURCES:

Territorial Lordships in the Principality of Salerno 1050 – 1150.

By Valery Ramseyer

In: Haskins Society Journal (2001), pp. 79 – 94

Exploring Valmarecchia. Diachrony of Population Development from the Roman Age to the Late Middle Ages in Central/Northern Italy: a Case Study of Emilia-Romagna (Southern Area) and Marche (Northern Area)

By Daniele Sacco

In: Lac 2014 Proceedings

Les structures du Latium médiéval : Le Latium méridional et la Sabine du IXe siecle a la fin du XIIe siècle.

By Pierre Toubert

Rome: École Française de Rome 1973

Architecture and Infrastructure in the Early Medieval Village. The Case of Tuscany

By Marco Valenti

In: Technology in Transition. A.D. 300 – 650. Ed. by Luke Lavan, Enrico Zanini and Alexander Sarantis. Brill, Leiden and Boston (2007), pp. 451 – 490

BEST INTRODUCTION:

Although much has been written about the Early Medieval history of the Italian hilltop villages, the best English introduction – altough nearly ten years old – it was written by Riccardo Francovich (1946 – 2007), who worked as an archaeologist at the University of Siena together with Marco Valenti and his team.

The Beginnings of Hilltop Villages in Early Medieval Tuscany

By Riccardo Francovich.

In: The Long Morning of Medieval Europe. New Directions in Early Medieval Studies. Ed. by Jennifer R. Davis and Michael McCormick Ashagate 2008 (Routledge 2016), pp. 55 – 82.

READ MORE:

From Constantine to Charlemagne: An Archaeology of Italy AD 300–800

By Neil Christie

Ashgate 2006 (Routledge 2016)

Framing the Early Middle Ages. Europe and the Mediterranean 400 – 800

By Chris Wickham

Oxford University Press 2005

Villa to Village: The Transformation of the Roman Countryside (Debates in Archaeology)

By Riccardo Francovich and Richard Hodges

Bristol Classical Press 2003

ISBN-10: 0715631926

ISBN-13: 978-0715631928

VISIT:

Rocca San Silvestro

Rocca San Silvestro

Parco Archeominerario di San Silvestro

Area Naturale Protetta di Interesse Locale San Silvestro – Val di Cornia

Via di S. Vincenzo, 34/b

57021 Campiglia Marittima Livorno

Italy

Archeodromo Poggibonsi

Archeodromo Poggibonsi

Parco Archeologico di Poggibonsi

Fortezza Medicea, Poggibonsi (SI)

The Archeodromo is an open air museum which aims to create a full-scale rebuilding of the the core of the village from the 9th century as it was excavated a few meters away. Central is the large longhouse, of over 140 square meters, divided into a domestic area, a granary and an area dedicated to activities of daily living. Here the opportunity is to learn about about the small community of farmers and craftsmen, living in huts around the large house, and carrying out their duties according to the lord of the manor. The blacksmith forge weapons and tools, the carpenter carves wood, leather is and the baker grinds the grain and prepares the bread. Inside the house, the weaver at the loom works with colored yarns from the workshop of the dyer; Meanwhile the garden is cultivated. The aim is to do a faithful recreation, which presents the participants with in-depth knowledge of what life was really like at the end of the first millenium in the hill-top village at Poggobonsi. each year, numerous events, summer schools and acdemic conferences are organised on site.

READ MORE: