Recent studies explore the connection between medieval climate changes and historical migrations in the North Eastern European regions bordering the White, the Barents, and the Kara See

It is well-known that climatic changes hit “the hardest” in transitional climatic zones, where human modes of production and patterns of exploitation push towards the limits. In times of favourable climatic changes, possibilities may open up, which later gets hit in times of climatic worsening. These facts govern both areas threatened by desertification in the Mediterranean and the exploitation of the Arctic Coast in Northern Russia. A new study explores the economic and demographical shifts in this area as reflections of climatic changes.

North Eastern Europe

The extreme North Eastern Europe constitutes a marginal historical transition zone cut off from the, at least partially, agriculturally based economy of Northern Russia and the hunting-gathering economy of the indigenous Finnish and Samoyed peoples of the North.

Climate and trade were early on crucial for the economy, and these are assumed to be the two main factors in understanding the regional historical development since the early middle ages.

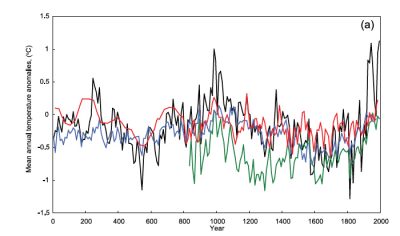

In a recent article, Vladimir Klimenko, has presented a multi-archive mean temperature reconstruction for this specific region and spanning 2000 years. He argues that Medieval climate had a profound impact on the Slavic population’s economy and directions of migration, facilitating penetration into higher latitudes in warmer and abandonment in colder climatic phases.

The Climate

The reconstruction shows that the Roman Optimum was followed by the cold epoch of the Migration Period (5th – 6th centuries), the Medieval Warm Period (10th to 12th centuries), and the notable cooling off during the “Little Ice Age”. However, sharp cold spells could be detected, for instance in the unidentified tropical eruption in AD 639, the eruption of Ksudach in AD 900, and the event in AD 1453, when the volcano, Kuwae, erupted.

Further, and perhaps more groundbreaking, the reconstruction also displays quick alternations between warm and cold periods, as is common at high altitudes. Some of these periods consisted of 2 – 4 decades of significantly warmer periods inside otherwise prolonged cold stages. These warm periods covered the following decades:

- AD 1350 – 1370

- AD 1400 – 1440

- AD 1470 – 1510

- AD 1770 – 1810

During these periods temperature might even exceed modern values, thus constituting main impulses for the pioneering and colonization of the North.

General overview

Based on this overview of climatic changes, Klimenko proceeds to describe the demographic and economic contractions and expansions as reflections thereof.

He notes that in the late 4th century the great migrations also included the Slavs, who settled the territories of the future Kievan Rus. Here they met up with Baltic and Finnish people in the area east of present-day Estonia, with whom they culturally mixed.

Around the beginning of the 8th century when climate began to warm up, the area around Ilmen was further populated by a mixture of Slavs and Scandinavians. This region was bordered to the east by a climatic cold zone around Mologa.

Later – in the Medieval Warm period (10th – 12th centuries) – an expansion eastwards resulted in the founding of cities like Novgorod and Ladoga by the Varangians and trading posts by lake Beloye. The populated region obviously expanded first towards the East, and later towards the North. Along rivers, creeks and lakes people began settling further up towards the rich hunting grounds of the Lapps. Chronicles also tells that people began seeking north and east in order to evade the looming Christianisation evoked by Vladimir.

Later around 1300, the Norwegians built a fortress at Vardø at the Northern-most tip of Norway in order to protect against Russians, who had been moving up along the shores of the White Sea, where networks of pogosts – trading posts – were erected. At the same time people in this region began to supplement their hunting and fishing with regular farming and herds of dairy cattle. From this period on, old Russian and Karelian historical monuments from the Middle Ages witness to the expansion. Also, a series of negotiations led to tractates signed by the Norwegians and the Novgorodians witness to the need to lay down the rules for merchants plying the fur-trade in the Finnmark.

Building on this Klimenko proceeds to detail the different expansions and contractions, which followed; but he also demonstrates how they may be clearly linked to the sometimes quite dramatic shifts in climate. This was for instance the case with the pulses of expansion along the Mezen River, which has been mapped. In general, though, a substantial number of settlements did disappear during the 16th and 17th centuries (The Little Ice Age), while contractions can be noticed elsewhere. Most of these movements can be directly linked to specific variations in the climatic cycles.

It is virtually certain that the mode and speed of development and expansion into the North of present-day Russia from the Middle Ages and into modern time was in many ways dependent on natural and geographical factors, writes Klimenko as a conclusion.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Vladimir Klimenko, Global Energy Problems Laboratory, Moscow Power Engineering Institute, 14, Krasnokazarmennaya St., Moscow 111250, Russia.

SOURCE:

Thousand-year history of northeastern Europe exploration in the context of climatic change: Medieval to early modern times

By Vladimir Klimenk

In: The Holocene 2016, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 365 –379