REVIEW: New excellent book tells the story of the mythological centre in Gl. Lejre c. 500 -1000 from an archaeological and historical point of perspective. It really deserves to be translated

Because I have heard marvellous things about their ancient sacrifices, I will not allow these to pass unnoticed. In those parts, the centre of the kingdom [of the Danes] is a place called Lejre, in the region of Seeland. Every nine years, in the month of January, after the day of which we celebrate the appearance of the Lord [6 January], they all convene here and offer their gods a burnt offering of ninety-nine human beings and as many horses along with dogs and cock – the latter being used in place of hawks. As I have said, they were convinced that these would do service for them with those who dwell beneath the earth and ensure their forgiveness for any misdeeds. (Thietmar of Merseburg, Book 1: 17. Here quoted from: Ottonian Germany. The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg. Translated and annotated by David A. Warner. Manchester University Press 2001, p. 80)

Thietmar was a bishop in Merseburg, a German city south of Magdeburg on the river Elbe. But he was also the author of a famous chronicle, which he wrote from 1013 – 1018, and which deals with the events not only in Ottonian Germany but also among its neighbours. One of these was the Kingdom of Denmark, which at that time (during the reign of Canute the Great) had expanded into a northern empire comprising England, Denmark, Norway and parts of present-day Sweden. Given this, it seemed natural to him to tell the story about Lejre quoted above. Currently, a small and insignificant village south of Roskilde (now called “Gammel Lejre”) archaeologists have documented the existence of a large Viking complex of halls, a market place and an impressive burial grounds.

It is a wild scene, and most commentators tend to regard the number of sacrifices as a reflection of Thietmar’s general tendency to describe the Scandinavians and Slavs as a wild and uncivilised people. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy, that Lejre early on played such a significant role in the mythology of the very early history of Denmark that Thietmar felt the need to name it as the “national” centre par excellence. Later Danish and Icelandic chronicles fleshed it out by recounting the heroic and legendary deeds of the Scyldings – Skjoldungerne – said to have had their royal seat there; as did the poem about Beowulf, although the poet does not locate the ancient seat of the Scyldings anywhere except in mythical Heorot, the famous hall and royal seat of King Hroðgar.

Nowadays, no one believes that Beowulf – or for that matter the later chroniclers – can be mined for any exact information about the heroic deeds of these very early mythological kings. However, excavations at Lejre continues to yield new information about what was undoubtedly a crucial royal centre in a period when Denmark was slowly turning into a proper medieval kingdom.

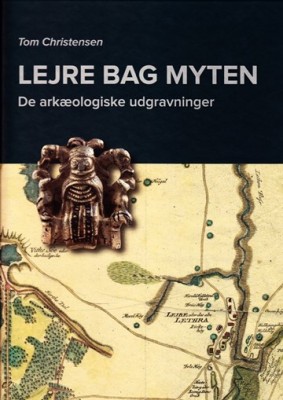

For years, the archaeologist Tom Christensen has excavated the site. Recently, he published the results in an important book about the history behind the site. Included is a report about the spectacular finds, which continued to surface even as he was writing. Although the book is in Danish, it deserves a review here, not least because it is the first time the many diverse finds have been thought through from one end to the other. The reader is thus very generously invited into the laboratory of a seasoned archaeologist, while he is exploring multiple inroads into this very complicated material. The result is an interesting history, which covers a period from c. 400 and up until the 19th century, when national romanticism re-discovered the myths and once more turned Gammel Lejre into a national hot-spot. The main object, though, is to present the report on the excavations and the many stray finds made by metal-detectors, accompanied by a careful sifting of the chronicles and other written sources, and the broader landscape. In the back is a full catalogue of the many finds.

Place Name: Lejre

In itself the name Lejre is rare. It is thought that its original meaning was ‘shed’ or ‘tent’; perhaps it means the place where people got together and set up a camp? Today, the meaning of the Danish word “lejr” is still “camp-site” (spejderlejr= scout-camp).

It is located on a hilly stretch lying to the west of two small rivers and with an old road running along the riverbed. It was populated in the Bronze Age as indicated by several barrows. Some may still be noticed in the landscape, while others may be found on old maps. Today a small village lies in the vale. Naturally, excavations in the village proper are restricted, but remains of an older settlement characterised by the activity of craftsmen have been located here, through which a road leads to the Firth of Roskilde (apparently the streams were never navigable).

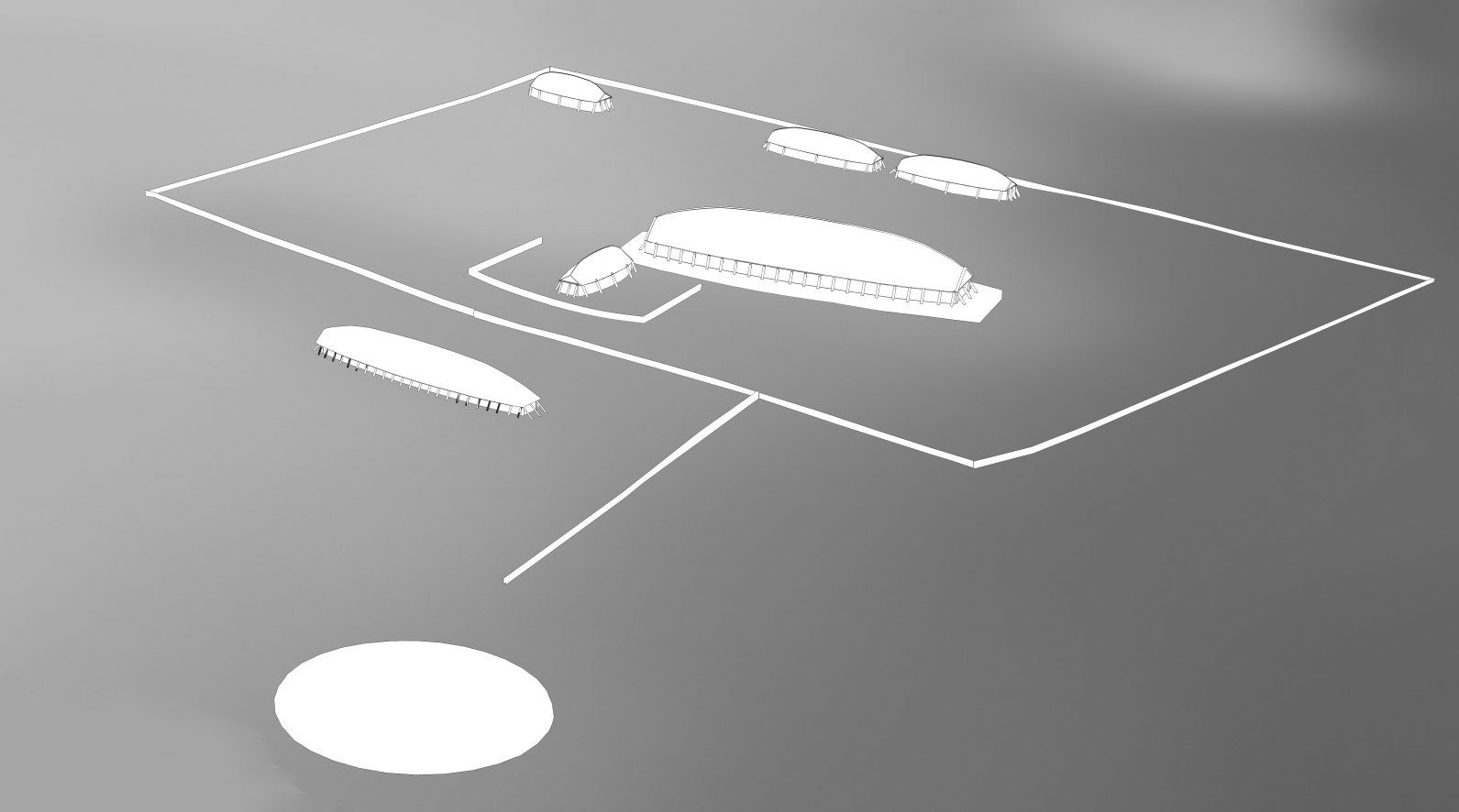

The real interest, though, are the results of the excavations carried it out on either side of the present village. Down by the rivers on the embankment of an isthmus may be found the remains of a Viking Age burial ground including the remains of four stone-ships from the first half of the 9th century and excavated in the second part of the 20th century. To the west of the village on hilly slope, a series of halls and other buildings were found. Both areas have only been partly excavated, and new information may be expected to keep adding to our knowledge about the history of the place.

First Phase: Fredshøj ca. 500 – 600

The first settlement at Fredshøj can be dated to c. 500 – 600. This compound contained a large hall 47 m long, with three-aisled construction, slightly curved walls and a width of seven meters at the centre and five meters at the ends. Fitted with prominent, daubed and whitewashed gables, it was probably a rather high building. It will have been visible from afar by people travelling to the place along the road down below. Next to this hall was found the signs of yet another building, but the interpretation is not entirely clear. Nearby a stone heap (perhaps a “hørg”) was discovered which had been exposed to fire and with infill consisting of animal bones, primarily domesticated animals. 52% of the bones came from pigs, while 33% stemmed from cattle and the rest from sheep and goats. Noticeable was the percentage of piglets signalling a surplus or elite economy. The same message is perhaps sent by the remains of a marten, which might have been hunted for the pelt. Remains of red and fallow deer plus ducks, geese and fish also contributed to the menu. Finally, a number of birds of prey seem to have been hunted, perhaps for the use of the feathers. It appears the animals were brought alive to the place and killed on site near the stone heap – perhaps this was indeed a “hørg”, a visible heap of stones used for sacrifices.

The name of the location “Fredshøj” – Peace Barrow – signals that the first hall was located next to a site, which might have been cordoned off for judiciary dealings. Nearby – to the west – a significant find of a golden bracteate from the 6th century plus an earlier find of a golden treasure signifies the importance of the place as a cultic and political centre at this point.

From around AD 650 the remains of princely burial were excavated down by the river in a barrow called Grydehøj. Unfortunately, the man and his grave-goods had been cremated. A profusion of melted bronze and gold as well as sacrificed animals, nevertheless, testified to his wealth.

Second Phase: Mysselhøjgård ca. 600 – 900

In the beginning of the 7th century the site at Fredshøj was abandoned and moved approximately fifty meters south to a new location called Mysselhøjgaard. This move was accompanied by a more complex settlement divided into two parts, ditched and fenced. To the north, the great hall was rebuilt, though now on a magnificent platform constructed of stones and with an even more impressive gable. The hall was built on the slope, probably using this to make the gable signal a very high and impressive building. Lesser houses were constructed to the south. Some claim that these were part of a sacred inner court or temple-ground, but to this Christiansen does not agree. He regards the house(s) as private homes for the elite.

The construction of a new stone heap was added . As the Mysselhøjgård-site was used for a longer period, the remains of animals appear to have been moved around from time to time, when other rebuilding and internal relocation took place. The composition of the herd of animals is comparable to that found at Fredshøj but expanded with several horses, dogs, wild hogs, a beaver plus a more substantial element of deer. Elsewhere on the site, pieces from the skull of a bear were found. It might have come from an imported bearskin, perhaps used in a ritual context. Another enigmatic find, a pierced piece of an antler, might have been fixed to a mask.

From this phase, stems an “eye” from an elaborate helmet of the Sutton Hoo-type. Found at Gevninge to the north of lejre, the “eye” indicates this village as the port to the “royal” site at Lejre. The “eye” is unique in a Danish context.

Third phase: Mysselhøjgaard c. 875 -1050

Finally, around 900, the hall was moved once more. Now located in the southern part of the hilly slope, the old site of the hall from phase two was given over to a burial ground. At excavation, the burial of a 35 to 50- year older man was found in the exact centre of the old – now defunct – hall. His grave was furnished with a fire steel, a knife with a handle wrapped in silver, and a fragment of what must have been a dress with gold-embroidered ornaments. The man had been buried in a coffin. Outside the defunct hall, several other burials were found. Holding elderly people, these burials belonged to the hardworking retainers at the bottom of society. Tom Christensen speculates that the site of the old hall was chosen as a “burial gift” to one of the leaders of society. None of the minions buried in its periphery appears to have been the victims of a sacrificial killing. This, however, was the case with one of the other burials down by the river, where a 35 to 55-old man had been buried with his hands and feet tied, and whose head had been chopped off. He was laid to rest in a grave with a 25 to 40-year old man. The very large stone ship (80 – 100 metre long) nearby has been dated to the 10th century.

The hall itself changed slightly. Now the architecture became reminiscent of the last great halls of the “Trelleborg-Type” and was characterised by further internal partitioning. It is during this period, the importance of Jelling as a probably competing centre grew, while Roskilde with a very early church from around 1000 took over as the regional centre. Around 1050 it is obvious the status of Lejre had faded. However – as is apparent from Thietmar – it retained somewhat ill-reputed fame until the chroniclers in the 12th century began anew to retell the old heroic fairy tales. It is perhaps significant that no church was ever built on site. This church, to which Lejre was attached came to be built two km to the south in the village of Allerslev. Perhaps there were too many heathen connotations still afoot?

The story of Lejre, though, does not end there. Significant finds suggest that royal and later noble interests continued to set their mark upon the village. And Tom Christensen tells this story as well in his brand new book, which also presents the final neo-romantic revitalisation, which took place in the 19th century.

To conclude: Evidently, Lejre was a regional if not a “royal” centre functioning continuously from 500 -1000 and with a special significance from 600 – 900. It may very well have been the real cradle of Denmark as opposed to Jelling, which looks more and more like a short-lived, though impressive “upstart”. Recently, though, the discovery of a comparable site at Erritsø in Jutland has questioned this conclusion. It seems archaeology continues to offer tantalising glimpses into the formation of the early kingdom of Denmark, pushing the date backwards.

Well done! The book deserves a translation into English.

Karen Schousboe

Lejre bag myten. De arkæologiske udgravninger.

Lejre bag myten. De arkæologiske udgravninger.

By Tom Christensen

Romu/Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab 2015

ISBN: 978 87 88415 96 4

Lejre beyond the Legend – the Archaeological Evidence

By Tom Christensen

In: Siedlungs- and Küstenforschung im südlichen Nordseegebiet (2010) Vol. 33, pp.237 -254.

READ MORE:

‘Medieval News’ from May 2016 brings you stories about Lejre in the land of the Scyldings and Beowulf, which is about to be unlocked. But it also shares a lot of notices about upcoming conferences, new books etc….

‘Medieval News’ from May 2016 brings you stories about Lejre in the land of the Scyldings and Beowulf, which is about to be unlocked. But it also shares a lot of notices about upcoming conferences, new books etc….