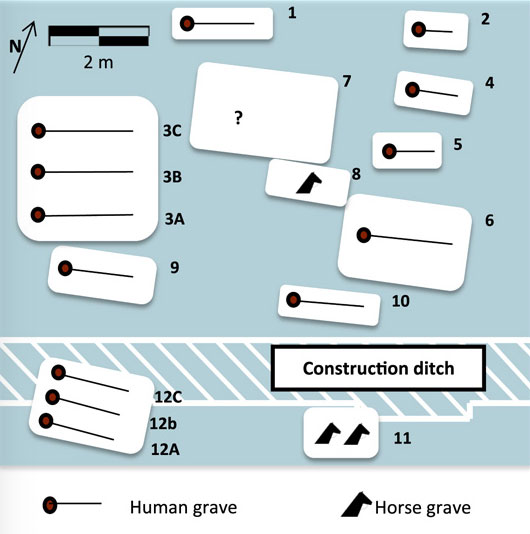

In 1962 an Alemannic graveyard in Niederstotzingen in Southern Germany was discovered and excavated. New studies of the aDNA of thirteen individuals – ten male adults and three infants – presents a snapshot of the local group of warriors.

The Alemannic graveyard in Niederstozingen dated to the end of the 6th century is famous for three reasons. First of all, the results were published soon after the excavation. Thus it came to define a horizon, against which other and later excavated burial grounds were compared. Secondly, some of the grave goods were exceptional, particularly the helmet and armour made in a Byzantine style from overlapping scales. Thirdly, one of the buried individuals was later identified as a woman, albeit buried with “male” grave-goods, This raised a scholarly debate on the phenomena of “amazons” in the migration period.

Recently, new studies were published adding to as well as offering corrections to the general understanding of the graves, the grave-goods, the interred individuals and not least the social structure of the group. The studies were carried out by researchers at the Eurac Research Centre in Bozen-Bolzano, Italy, and at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, in Germany.

No female warrior

First of all, the new studies laid the question of a “female” warrior to rest. Eleven of the thirteen individuals had enough DNA preserved to identify them as males, while no definitive sex could be determined for two. But “she” was not among these two. Accordingly, the graves witness to a burial practice with males to one side, and females to the other. If women were ever buried at the site, they were later translated from a pillaged grave and moved elsewhere.

Also, analyses of strontium showed that eleven out of thirteen individuals had grown up and lived locally, while two individuals, who had grown up in another locality, had lived as grown-ups in Niederstotzingen. These two individuals were further characterised by the wear and tear on their skeletons, signalling that they were professional soldiers. One of these individuals probably derived from Southern or South Eastern Europe.

A recent study of the aDNA of all the individuals aimed to reconstruct patterns of kinship. This new information has helped shed even more light on the cultural context presented by the funerary artefacts.

Genome-wide analyses helped to estimate the genetic affiliation of the majority to modern West Eurasians. Of these, at least five individuals belonged to the same patrilinear kin-group, consisting of two brothers – obviously leaders of the group – one of which had two sons, and a grandchild, thus constituting three generations. Mothers, though, had judged by the mapping of haplogroups been recruited from far away, confirming the results from other similar investigations that marriages were exogenous and patrilocal.

Panoply of grave goods

Remarkably, though, neither kinship nor geographical origin could be related to the different ensembles of grave-goods. Thus, the objects found in the graves of the five individuals, who were identified as belonging to the same patrilineal kin-group, could be characterised as Byzantine, Franconian, as well as Lombardian. Especially the two assemblages, belonging to the two brothers in the first generation, are unusual: one was Byzantine, while the other was Franconian. Compared with the finds in all twelve graves, both these interred individuals were laid to rest with the most magnificent objects – respectively the Byzantine Helmet and the Franconian double-edged-ring-sword together with an engraved lance. In this context, it is interesting to note that the study of the strontium profiles of the two brothers showed that they had not only been born locally, they had for several years also lived together locally. Which means that we have two brothers born and living together with descendants and retinue while showing off military equipment of very diverse cultural styles. It does not seem farfetched to imagine that they laid their hands on the weapons and armour as part of raids less than gifts from the war-lords, for whose service, they had signed up. Perhaps, though, the Franconian Ring-sword did represent a gift from a Merovingian overlord recruiting our man to be the local official representative.

The research group publishing the results conclude that kinship and fellowship was held in equal regard. We might add, that the findings also show the outline of a small band of brothers with their retinue, who had settled on the crossroad of two former Roman highways living off the countryside as early medieval highway robbers. Or as the authors write, they constituted a “military outpost guarding an important land route”. The remaining question is: would there be a difference?

Sadly, the corresponding female burial ground has not been found and excavated.

SOURCE:

DNA of early medieval Alemannic warriors and their entourage decoded

Researchers from Eurac Research and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History have analyzed human remains dated between 590 and 630 CE

EURAC RESEARCH/press Release September 2018

READ:

Ancient genome-wide analyses infer kinship structure in an Early Medieval Alemannic graveyard.

by Niall O’Sullivan, Cosimo Posth, Valentina Coia, Verena J. Schuenemann, T. Douglas Price, Joachim Wahl, Ron Pinhasi, Albert Zink, Johannes Krause, Frank Maixner. Ancient genome-wide analyses infer kinship structure in an Early Medieval Alemannic graveyard. Science Advances( 2018), vol. 4, no. 9

Neue Erkenntnisse zur frühmittelalterlichen Separatgrablege von Niederstotzingen, Kreis Heidenheim

By Joachim Wahl, Giovanna Cipollini, Valentina Coia, Michael Francken, Katerina Harvati-Papatheodorou, Mi-Ra Kim, Frank Maixner, Niall O’Sullivan, T. Douglas Price, Dieter Quast, Nivien Speith and Albert Zink. (2014)

In: Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg (2014) vol. 34, 2 p. 341-390

Helm und Ringschwet. Prunkbewaffnung und Rangabzeichen germanischer Krieger. Eine Übersicht.

By Heiko Stuer

In: Studien zur Sachsenforschung (1987) Vol. 6, pp. 190 – 236.

READ ALSO: