Since Carolingian times, German kings and emperors possessed large tracts of land around the Harz. Later, the rich silver mines in Rammelsberg gave rise to the construction of a splendid palace complex in Goslar.

Since the Carolingian times, the German kings and emperors possessed large tracts of land around the Harz. Later, the rich silver mines in Rammelsberg gave rise to the construction of a splendid palace complex in Goslar.

In Carolingian times, the fertile hunting grounds in the Harz gave rise to the consolidation of an important domain. First controlled by the Liudolfinger, the Saxon dukes, it became an important royal centre, when their descendants were elected as kings and emperors in the 10th century. Known as the Ottonians, they ruled this heartland from a fortification, located on a plain north of the Harz mountains, at Werla. In mid 10th century, however, important silver mines were opened up 16 km south in the Rammelsberg near present day Goslar, and archaeologists have found traces of what is believed to have been an early settlement. Written sources tell us there were a hunting lodge and a mill. Gradually, though, the place became more important as synods and diets were held there while Henry II (973 -1024) increasingly witnessed royal charters at Goslar.

The first of these was organised in March 1009, and witness to the logistics involved in gathering Saxon nobles and church officials to this place. No wonder, archaeologists have found evidence of a royal palace and in all probability a chapel c. 20 m to the east of the present hall. According to Uvo Hoelscher, who excavated the place at the beginning of the 20th century, the fundaments of the royal hall indicate a wooden hall with an attached chapel to the south. There must have been a chapel, as synods, as well as assemblies, were held there.

It is believed that the move from the old Saxon meeting place, Werla, to Goslar represented a conscious symbolic shift. No longer would the old traditional assemblies be held in a place steeped in Saxon history; it would have moved to a location, where the basis for royal power was now accumulated: near the silver mines, rediscovered in the 10th century. After 1013, only one more meeting at Werla is documented. After 1035 every activity had moved to Goslar.

The New Chapel

The Royal Palace in Goslar, which is still standing, witness to this symbolic act. Built on the foothill of Rammelsberg it nestled above a site, which was obviously carefully chosen. With ample water from the river Gose, it could service as a meeting place for numerous counts and clerics together with their retinues and horses.

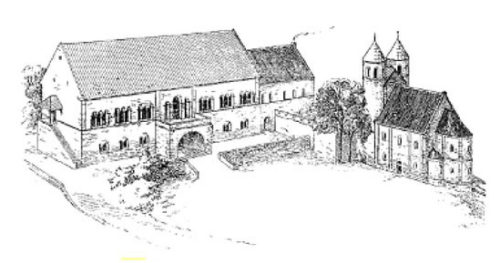

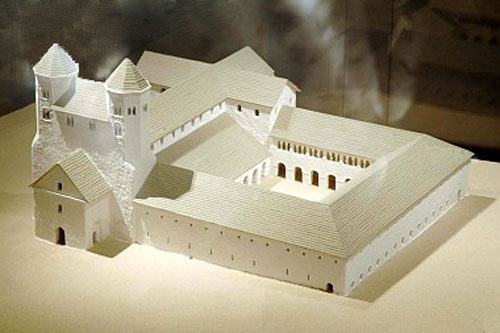

The first building spree was a chapel commissioned by Queen Gisela (990 – 1043). It is not known exactly at what point in time the royal chapel was erected, but sometime after 1024 is likely. At the same time, the palace must have been built, as foundations were laid 20 metres to the west, enabling the construction of a covered passage between the chapel and the royal apartments annexed to the new royal hall. This chapel, which according to Thangmar, was constructed by Godehard of Hildesheim, measured 22 metres in length and was 12 metres wide. It was a so-called double-chapel with a ground floor reserved for royal servants and retinue, with the upper floor reserved for the royal family, who was in all likely hood able to walk across from their private apartment and enter the upper level of the chapel from there.

The New Palace

In 1031, 1034, and 1038 Conrad II (c. 990 – 1039) and Gisela spent Christmas together with their household at Goslar, indicating its role as the most important haven of the new Salian dynasty. It is highly likely that a precursor to the magnificent palace was already in place when Conrad died in 1039 and left the reigns to his young heir, Henry III.

It is nevertheless believed that the new king was responsible for the building, which constitutes the core of the present imperial palace. Measuring 54 metres long and 18 metres wide it held a guard’s room on the ground floor and a throne room on the second. To the north was a side-building holding the imperial apartments with – as suggested by Hoeschler – a kitchen on the ground floor, offering warmth for the private apartment on the upper floor. It must have been a snug and pleasant place to stay, as Henry III, his family and retinue repeatedly spent Christmas there. But exactly how advanced the heating facilities were, is hard to say. According to Hoeschler, the hypocaust in the ground floor of the long hall was not constructed until late in the 11th century. The long hall at the ground was called the “Winterhall”.

The Collegiate Church

The new king, however, was without doubt responsible for expanding the complex to the east, commissioning the construction of an impressive church, dedicated to SS Simon and Jude. Intended as a full religious institution housing a reformed collegiate of Benedictine canons, it came with refectory, cloister, chapter, etc. Torn down in 1810, only the entrance to the north remains. Nevertheless, the sources tell us it was built sometime between 1040 – 50, with three naves, a west-work with two towers and three apses to the east. A crypt was under the chancel.

It is believed that Henry III donated the impressive Codex Aureus Goslariensis at the consecration of the church in 1051. Two important pieces of sculpture have been preserved from that time, the altar and the Imperial throne. Symbolic of the lack of effort by the authorities in Goslar to tell this story, one is exhibited in the museum in the palace while the other is kept in the local museum. Both are outstanding pieces of bronze-casting from the 11th century and relics of the mining operations in Rammelsberg; they ought to be exhibited together.

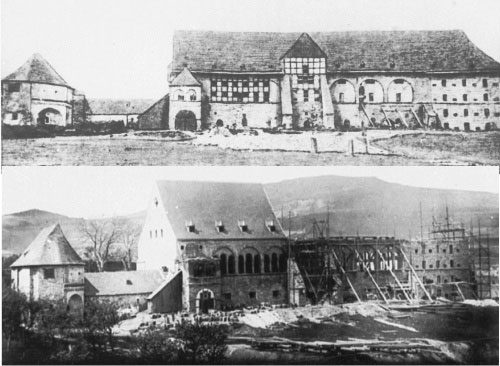

Later, around 1200, the north portico was added; this is the only bit left standing when the church was demolished 1819 – 22. The same fate nearly hit the imperial palace, which had fallen into disuse already in the later Middle Ages. It was only through luck it was “discovered” by nationalists in the 1860s who had it rebuilt to accommodate the romantic ideas of Goslar as the heartland of the new German Empire. The rebuilding began in 1868, but when the Emperor visited the construction site in 1875, it gained national importance. This led to the decoration plan by Hermann Wislicenus, who painted a series of grandiose and monumental wall paintings celebrating the new dynasty of emperors as well as various scenes from German history with scenes from the life of the Ottonian, Salian and Staufian emperors.

SOURCE:

Das Goslarer Kaiserhaus. Eine baugeschichtliche Untersuchung.

By Wolfgang Frontzek, Torsten Memmert and Martin Möhle. In: Goslarer Fundus.

Veröffentlichungen des Stadtsarchivs, Vol 2. Goslar Stadt,

Georg Olms Verlag 1996

Die Kaiserpfalz Goslar

von Uvo Hoelscher and Martin Möhle (Vorwort)

Series: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Stadt Goslar / Goslarer Fundus

Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, (1927) 1996

SEE MORE:

The Cathedral reconstructed in 3D by TU Clausthal, 2000