The chance of dying from violence in the Middle Age was at least five times higher than today. It appears culture and state-formation have an essential peacekeeping role to play.

Currently, NATO Troops are being posted in Eastern Europe to stave off future Russian aggression and the threat of the Ukrainian war spilling over. Meanwhile, the Chinese are threatening the USA with grave consequences if the status of Taiwan is questioned and the build-up of artificial islands in the South China Sea is hindered. Also, it seems all-out atomic war is once more threatening the horizon. One should have thought that the horrors of the 20th century would stop even the most foolish and self-engrossed dictator, but apparently, this is not the case.

The question is: do we not get wiser?

This question has, of course, been voiced for as long as historians, philosophers and social scientists have studied the psychological, sociological and historical roots of violence. However, recently, a Spanish group of scientists had a letter posted in Nature, which asked the question in a somewhat different manner: they asked what role did the phylogenetic – that is, long-term evolutionary – roots and levels of lethal human violence play? And to what extent might we register shifts in these levels of violence at different times compared to the inherently violent nature of hominids? And under what societal circumstances.

Lethal Violence among Mammals

From an evolutionary point of view, lethal violence is seen as an adaptive strategy favouring the perpetrator’s reproductive success in terms of mates, status and resources; this, of course, implies that as evolution proceeds, we might tend to get more violent than our forbears. Apparently, though, this is not the case.

By contrast, specific ecological and cultural contexts may further or hamper these traits, creating milieus where violence does not pay off. For example, high incarceration levels for young males in a given society might seriously impede their possibilities to procreate and thus contribute to the dispersal of their violent “genes”. Or violent males left out of the polygamous matrimonial markets at home might inflict horrors abroad (but not at home). As the authors write: “disentangling the relative importance of cultural and non-cultural components of human violence is challenging, owing to the complex interactions between ecological, social, behavioural and genetic factors” (p. 233)

However, violence is not specific to humans; it is also prevalent among primates, which exhibit high levels of intergroup aggression and infanticide. There is a level of aggression that can be detected among mammals in general.

To study the complex problem in detail, the scientists set out to quantify the level of lethal violence in 1,024 mammalian species from 137 different families and, parallel to this, 600 human populations, ranging from the Palaeolithic era to the present. The level of lethal violence was defined as the probability of dying from intraspecific violence compared to all other causes.

Lethal violence was found among 40% of the studied mammal species, but the authors consider this a low estimate. Interestingly, the conclusion was also that the level of lethal violence was higher in social and territorial species than in solitary and non-territorial species.

Discounting this difference, the level of violence was 2.0 +/-0.02% of all deaths. However, when territoriality and sociability entered the equation, the level was measured at 2.1 +/-0.02%.

The next phase in the study was to explore humans through statistical studies of graveyards. Based on this analysis, the scientists concluded that the level of lethal violence during human prehistory did not differ from the phylogenetic prediction. However, comparing humans living under specific circumstances (old world/new world/ancient, medieval or modern periods), they seemed to differ in their levels of violence.

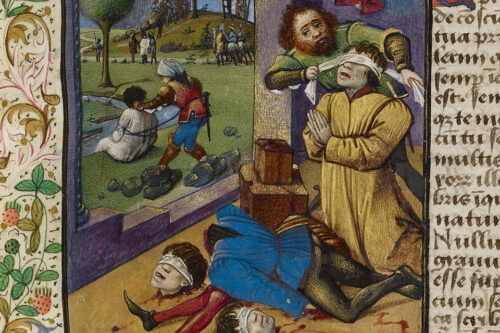

The Middle Ages

These studies demonstrated that the chances of dying from lethal violence in the Iron and Middle Ages were no longer hovering around 2% but significantly higher, namely 7.7 – 8.1 %. However, moving into the modern age, the chances of dying from violence fell substantially. In contemporary times, this is even more reduced. How come?

One proposition was that levels of lethal violence would inflate when population density grew, but the opposite was, in fact, the case. “High population density is therefore probably a consequence of successful pacification, rather than a cause of strife”, writes the authors.

Further, exploring the levels of lethal violence inside specific types of social formation – bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states led to another fascinating conclusion. Life in societies governed by chiefs was nearly 6% more violent than expected. Conversely, life in formalised states, characterised by monopolised violence (armies and police), would be less violent than levels of inherent violence should otherwise indicate; specifically, this is the case for developed modern states.

Thus, people in the Middle Ages were seven to eight times more likely to die from lethal violence than their descendants – us – living in modern times. One reason for our more civilised behaviour is – claims the authors that we live in societies governed by heads of state and not as members of clans governed by chiefs.

Conclusion

“At the dawn of humankind, people were as violent as might be expected considering the common mammalian evolutionary history.” Later, however, this prehistoric level considerably shifted according to people’s socio-political type of organisation. This conclusion suggests that not just genetically conditioned habitual levels of violence dictate our chances of dying from aggression; culture can modulate the phylogenetically inherited lethal violence in humans, they conclude.

Naturally, the study has been queried. Especially questions about the historical material, which is probably skewed, must be raised. For example, did dead warriors and soldiers at all times get transported back to be buried in their local cemetery? Or were they left on the battlefield to be scavenged by predators? Would people eventually have died of violence if they had not been subjected to plagues? Or do pestilences further the breakdown of civilising institutions as happed during the Black death? However, as the first report on the statistical relations between the inherent level of violence and that of specific historical periods and circumstances, the study is fascinating.

It also seems as: yes, indeed, we do get wiser.

SOURCE:

READ MORE:

READ ALSO:

Where Does Violence Come From? A Multidimensional Approach to Its Causes and Manifestations

By Bernhard Bogerts

Springer Verlag