From ca. 1000, Scandinavian pilgrims travelled south to reach the large centres. Registered in the Confraternity Book from Reichenau, we know the names of more than 700 Scandinavian pilgrims from the 11th and 12th centuries. A new research project aims to determine what these people were called back home and abroad.

• aystin • auk • astriþr • raistu • stina • aftir • kak • sun • sin •

Östen and Estrid raised the stones after Gag (?) their son. Source: Wikipedia

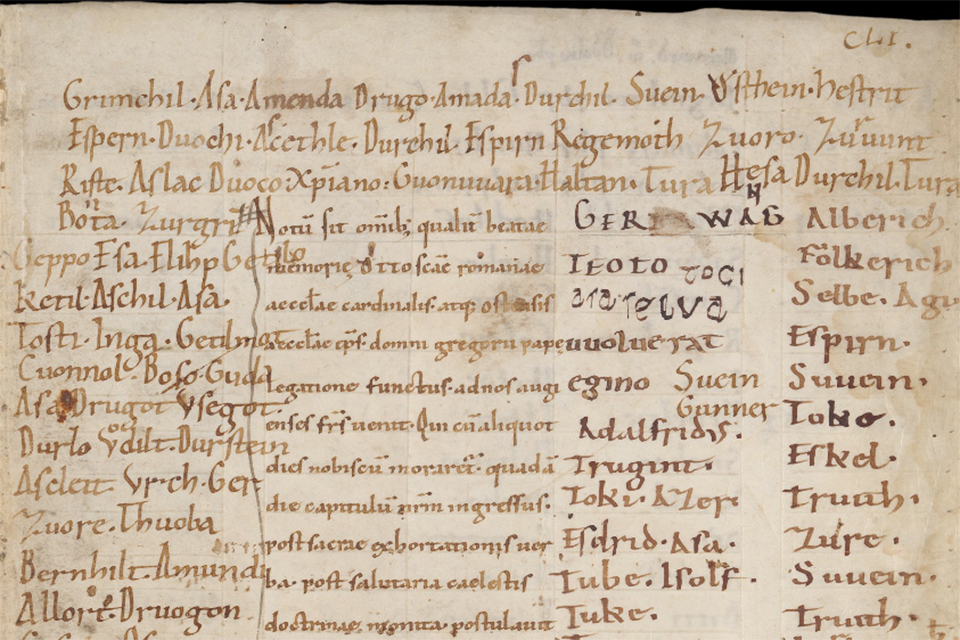

Æstriðr Sigfastsdotter was a remarkable woman. We know she lived in Broby Bro near Täby south of Uppsala ca. 1020-1080, where she raised several Runic stones to commemorate “Östen, her husband, who travelled to Jerusalem and died in Greece”, Gag, her son and other family members. Uniquely, though, we also know of her from the confraternity book (Liber Vitae) from the Abbey of Reichenau in Austria. Begun in AD 824, it was in use for centuries. One of the collections consists of 743 names from Scandinavia, registering pilgrims from the 101st-13th century. A few of these have even been identified as autographs. The majority, though, were written down by local scribes, who probably or often distorted their names, which most of us will have experienced occasionally. While Estrid’s name was spelt “astriþr”, her name – if it is the same person, was written “Hestrit” in Reichenau. The question is, why?

– The German-speaking monks in the monastery were challenged when they heard unfamiliar Nordic names and had to write them down, says Michelle Waldispühl, lecturer in German and leader of the project.

In 2019 a research project was launched at Göteborg University to study these names and the changes they underwent from north to south. The corpus, consisting of ca. 1000 North Germanic names recorded during the 1000-1300s, was initially edited in an online database.

Including the names, the variants, and digital records, the project has sought to improve the philological principles for the digital editions of historical personal names by considering both spelling variations and language contexts.

Primarily, though, the research project has aimed to explore the strategies employed when North Germanic personal names were adapted to medieval German, French or Latin in a multilingual context. What patterns might be detected, and why were different strategies followed? Previous research on names in historical language contact has focused on place names, whereas personal names are still underexplored. This project has sought to fill this gap.

– The historical context poses particular challenges in the analysis but also contributes some insights. For example, there seems to have been more room for “play” with name forms than today. Differences in adaptation methods cannot only be explained by linguistic differences but are primarily dependent on the scribes’ different spellings and approaches when writing the records, explains Michelle Waldispühl, who herself – as a Swiss living in Sweden – has experienced how language contacts can affect personal names.- Since my surname Waldispühl is not known in Sweden, it creates challenges in pronunciation and spelling. Somewhat similar to the ones the German monks faced. Some original spellings I have seen are Waldenspiel and Walspyl, she says.

Another modern dimension of the same complexity derives from the multiethnic mispronunciation of complicated “old” Scandinavian placenames used as surnames modern Scandinavians may encounter.

Waldispühl hopes that the database can be helpful for an interdisciplinary audience and that researchers from different fields, such as name researchers, linguists, and historians. She also hopes the database’sdatabase’s concept and structure may inspire future editions of names in similar texts.

The NordiCon database is part of the ongoing research project: “Many ways to spell correctly. Variation and language contact in medieval personal names”, funded by the Swedish Research Council until July 2023.

Currently, the results of the research are being published. However, the group hopes that the principles behind the construction of the database may be used in other comparative contexts.

What about Estrid?

Estrid Sigfastsdotter shared her name with fourteen other women mentioned on Swedish Runic Stones. From other sources, we know it was a “high status” name carried by several queens and princesses – to mention a few: Asfrid Odinkarsdotter, known from Runic inscriptions ca. 920, Estrid, who was married to Oluf Skötkonung (ca. 1000-1020), and Estrid Svensdatter, a sister to Cnut the Great (1000-1057). However, we cannot be sure that the “Astriþr” from Täby is identical to Hestrit in Reichenau. Although we know the name crops up together with the names of her husband and a younger son, the record of the three persons must have been made several generations later than their presumed visit of the couple. On the other hand, the list of names is tantalisingly close to the family recorded from Täby, and a possible explanation is that their son visited Reichenau at a later stage and at that time asked (or paid for) to have their names registered in the confraternity book. (For arguments for and against, see Edberg 2006 and Naumann 2009).

However, even if the persons are not identical, we should ask, what does the difference in spellings reflect? For example, does the added grapheme <h> in the German record reflect different conventions, different linguistic or sociolinguistic contexts, or even shifts indicative of the changing times?

- Should we “blame” the different alphabets used – Runic writing versus Latin? (Not likely, as the rune for <h> might have been used if this had made sense for the runecarver)

- Do we see a faithful linguistic rendition of a peculiarity of the dialect near Uppsala (the Uppsala-h:et) as suggested by Edberg (2006) reflecting a situation where Sven has orally presented the names to the scribe, who has been paid to register them in the book?

- Or is this a graphological adaptation to German simply reflecting the German scribe and his wish to render the record readable for his German brethren? Perhaps, even reflecting a more modern – medieval – turn of the language spoken at Reichenau at the end of the 11th century?

We don’t know. What we do know now – based on the studies carried it at Göteborg – is the complicated matter of names and their versionable and fluid character.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Liber Vitae from Reichenau. From Zürich Zentralbibliothek. MS Rh Hist 27 fol89r. CCBYSA. Inscription with Sven, Østen and Estrid in the upper right corner.

SOURCES

Personal names in medieval libri vitæ as a sociolinguistic resource

By Michelle Waldispühl and Christine Wallis

From the journal Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics (2023), Vol 9 No 1.

Spår efter en tidig Jerusalemsfärd

Av Rune Edberg

In: Fornvännen (2006) Vol 101, pp. 342- 347

Die nordischen Pilgernamen von der Reichenau im Kontext der Runennamenüberlieferung.

Naumann, Hans-Peter (2009).

In W. Heizmann & K. Schier (Eds.): Analecta Septentrionalia. Beiträge zur nordgermanischen Kultur- und Literaturgeschichte, 776–800. Berlin / New York: de Gruyter.