Debates concerning the gravity of the Black Death in 1348 and afterwards have been around for a long time. New scientific studies of pollen raise serious questions as to the death rate

Since the recent pandemic caused by Covid-19 hit the western world, historians have invested new energy in an old series of questions. For example, how devastating was the bubonic plague? Moreover, did it hit uniformly? Or were there significant differences between urbanised centres and the rural countryside? Furthermore, why was Norway hit so severely while Poland seemed to get off easily?

Since the recent pandemic caused by Covid-19 hit the western world, historians have invested new energy in an old series of questions. For example, how devastating was the bubonic plague? Moreover, did it hit uniformly? Or were there significant differences between urbanised centres and the rural countryside? Furthermore, why was Norway hit so severely while Poland seemed to get off easily?

For decades, this question has entertained late medieval historians trying to understand the notorious economic downturn ca. 1300 – 1500 and the social repercussions.

However, one of the challenges has been the multitude of sources stemming from some regions in Europe – for instance, Northern Italy – while others are decidedly lacking valid data (Denmark). With Norway, a puzzling outlier.

“The data is sufficiently widespread and numerous to make it likely that the Black Death swept away around 60% of Europe’s population,” Ole Benedictow, a Norwegian historian and one of the leading experts on the plague, wrote in 2005. When Benedictow published “The Complete Black Death” in 2021, he raised that estimate to 65%. Another comprehensive estimate by Bruce M. S. Campbell argues for a slightly lower estimate, between 30-50%. Nevertheless, astounding figures.

However, the last years have witnessed several more ingenious ways to gauge the impact than sifting through chronicles and tax lists from the 14th century. In 2017, scientists published a study evaluating the atmospheric lead concentration in the Colle Gnifetti Ice-core, showing a marked drop between 1349-53 and again in the mid 15th century. In this study, the lead concentration is seen as a sign of the total collapse of mining activities in Europe during the plague. Another study from East Anglia has presented the rises and fall in the number of potsherds in the period in numerous localities and backyards. Carried out in multiple locations as a community project, this study showed an average decline in numbers of shards measuring 44.7%, with cities experiencing a fall of 55%. This study is fascinating as it provides a model for local historians to do surveys elsewhere in Europe.

A common denominator for these studies is that, yes, the Bubonic Plague hit hard in some places, but not universally.

However, the scientist, Adam Izdebski, heading the pollen-project and an an environmental historian at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany goes a step further. In an interview in N.Y.Times, he says:

“We cannot any longer say that it killed half of Europe,” he tells us.

Pollen Profiles

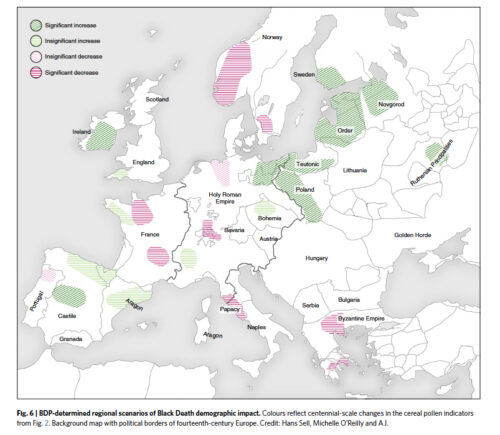

This statement is based on a newly published study of pollen from 261 radiocarbon-dated coring sites (lakes and wetlands) located across 19 modern-day European countries shows a very varied picture. Some places in Europe got off lightly, while others were devastated.

Recently, a group of scientists have argued that a shift in pollen species might present us with an answer. Every year, plants release pollen into the air, which ultimately falls to the bottom of lakes. Such studies are a mainstay of scientists who wish to understand the long-term shifts in our historic landscapes. However, they may also be used as indicators for the level of the agrarian exploitation of a region.

By measuring the amount of pollen from cultivated grains between AD 1250–1450, the level of agrarian activity can be measured precisely. By deferral, the area under plough may be regarded as a convenient proxy for the size of the working population at a given locale. Moreover, the results have afterwards been validated by a comparison of two well-studied regions in present-day Sweden and Poland. For instance, this shows a reduction in the agrarian production of app. 35% in the Swedish region, while Poland does not seem to have been touched at all. Finally, a comparison with the national payments to the papal administration of the Peter’s pence has also been carried out.

The result is a European map showing a significant variety in agricultural activity, which might be used to map the regional and local impact of the plague and its ensuing mortality. According to this map, Norway and Sweden were hit to the same extent as was Northern Italy and Northwestern France. As opposed to this, the Baltics and Central Europe got off lightly. In fact, this part of Europe experienced demographic growth. Unfortunately, no studies were sampled from The Low Countries and Flanders, which have been presented as one of the puzzling areas. Also, only Cornwall figures in the English material. Further, as a comparison, it might have been nice to have at least East Anglia included, where the study with the pot shards mentioned above was carried out.

The question is, of course, why did some places avoid a total catastrophe while others were hit with a hammer? How come the pandemic reached biblical proportions in some regions while others got off lightly

Several questions

The question, though, which seems to have preoccupied the scientists is whether such detailed characterisations of the different regions in Europe may be used to gauge the general impact of the plague per se.

No, says the authors of the new study. So far, the research only shows the value of regional explorations and comparisons rather than the ability to use the method for generalisations. The scientists do claim, however, that the demographic shifts detected in the pollen profiles indicate where the plague hit the hardest.

The authors write that “these inter-regional differences in the Black Death’s mortality across Europe demonstrate the significance of cultural, ecological, economic, societal and climatic factors that mediated the dissemination and impact of the disease. The complex interplay of these factors, along with the historical ecology of plague, should be a focus of future research on historical pandemics”.

However, this must, at best, be considered a tentative interpretation. What the study shows are demographic shifts inside Europe. These may or may not have been caused by the Black death.

However, should these shifts rather be seen as reflecting the opportunities offered for the survivors – many or few? Unfortunately, the study cannot tell us whether these shifts reflected increased mortality or people on the move in the wake of the plague.

Let us take the Swedish material, upon which the authors specifically touch. The regions studied here is the forested landscapes just north of the Danish regions – Scania, Halland, and Blekinge – which must be regarded as a frontier region. Rulership to these three wealthy provinces was disputed during the Middle Ages. Further, from at least 1345 and until the Nordic Union was established in 1397(1389), wars were continuously fought between the Danish-Norwegian and the Swedish-Baltic-German factions operating in the region. (From 1363-1389 Sweden was ruled by a German Prince, the Duke of Mecklenburg). In view of this, we cannot know precisely to what extent wars and subsequent migratory movements caused the demographic suppression in the border country between latter-day Denmark and Sweden, or whether the plague per se caused the depletion. Hence, when the authors write that their “BDP approach shows Black Death mortality was far more spatially heterogeneous than previously thought”, the conclusion is perhaps over-hasty. It may have been on the same scale, wherever it hit, but migratory moves – caused by the ensuing civil wars and violence – may have shifted the balance between neighbouring regions inside Europe.

Another example – not touched upon in the article – is the situation in France. Judging from the map, the pollen analysis shows that the regions hit the hardest in France where the exact provinces laid waste in the aftermath of the battle of Crécy in 1346 and the following battle at Poitiers in 1356 between the English and the French. At the latter, The French King, John II, was taken prisoner opening up Northern and Eastern France for the marauding English army, so-called free companies consisting of mercenaries and rebellious peasant uprisings. To read the chronicles from that period is to witness a failed state. No wonder peasants fled the countryside. Perhaps they went to Western Bretagne, a province marked by demographic and agricultural growth?

To conclude, the detection of areas of demographic decrease versus significant increase cannot be used to say much about the impact of the plague – neither regionally nor in a pan-European perspective.

However, the study tells us that to the extent the plague impacted demography, it might have been lessened or worsened by migratory movements caused by or following in the wake of the plague and the accompanying social and economic transformations in the later Middle Ages. Thus, the new study and the deployment of its method does present us with an exciting new tool to revisit the situation in the different regions inside Europe

Thus, the method is well situated to reveal patterns of agricultural activity, the impact of the plague AND the issuing migrations inside Europe and in a longer period span.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Fresco from the former Abbey of Saint André de Lavadieu in france. Source: Wikipedia/Khan Academy

SOURCES:

Palaeoecological data indicates land-use changes across Europe linked to spatial heterogeneity in mortality during the Black Death pandemic

By Izdebski, P. et al:

In: Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022) OPEN ACCESS

Did the ‘Black Death’ Really Kill Half of Europe? New Research Says No

By Carl Zimmer

N.Y.Times 10.02.2022