Henry III, a member of the Salian Dynasty, was nicknamed the Pious. With close-knit contacts to Cluny, he was an important champion of the “Peace and Truce of God” movement. But he was also a dedicated champion of the right of a crowned emperor to appoint bishops in his realm. As such, he laid the groundwork for the later investiture controversy, which came to be the all-out defining mark of the contentious rule of his son, Henry IV.

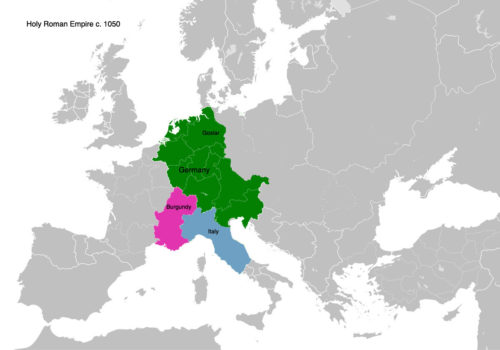

Henry, 1016 – 1056, was the eldest-born of Conrad II (c. 990 – 1039). Although the descendent of mid-level noblemen, the Counts of Speyer, Conrad succeeded in marrying wealth as well as later gaining the trust of the majority of his peers. Hence, when the Saxon dynasty, the Ottonians, died out in 1024, Conrad was elected king. Later, in 1027, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Rome. Of course, this was not achieved without rumbling and strife, and nobles instigated numerous rebellions during his reign. Nevertheless, Conrad II succeeded in gaining control of the largest duchies by placing his family members in charge of strategic positions. Central to this success was his use of the German Church as a vehicle for building the administration necessary to control his vast realm reaching from Hamburg to the south of Rome. Loyal church officials appointed to bishops became the willing vassals in this new order, where rebelling magnates were regularly accused of treason. This was a time when royal power sought to become more unassailable but also succeeded in gradually turning more and more controversial.

It is probably as part of this overall strategy that his son, Henry III, benefitted from more than a basic education. Henry’s first tutor was Bruno, who was not only bishop of Augsburg but also brother to the last Ottonian emperor, Henry II. Later, Egilbert, bishop of Freising took over. Another significant influence came from Wipo, who was a chaplain and court historian, employed by Conrad II. But Henry also followed his father around learning the craft of ruling. Thus, at the age of twelve, he was present in Rome at the imperial coronation of his father. Later, the same year, he was, at the age of twelve, designated “the hope of the Empire” and crowned king in Aachen. At the same time, he was appointed duke of both Bavaria and Swabia. In 1036, he became married to Gunhild of Denmark. However, she died a few years later, and in 1043, he married Agnes, a princess from Aquitaine.

Reign

Numerous rebellions and several wars waged against the Hungarians marked the reign of Henry III (1039 -1056). In 1039 he invaded Poland. This invasion was followed by a campaign into Bohemia, in which Henry was at first defeated, but later succeeded in succumbing the Bohemians. From this venture, he went further south, and in 1044 he defeated the Hungarians at Menfö at Raab. Nevertheless, countless revolts on the eastern frontiers continued to call for military campaigns. Given this, Henry III has been characterised as a mere warlord. Seen from one perspective, it seems as if he spent his lifetime on continuous campaigns against enemies like Bohemia and Hungary as well as on quelling more internal uprisings in Lothringia, Burgundy and Sachsen.

Central to this, however, was his collaboration with a vast network of bishops recruited from the royal chapel and his wider network of clerical friends. Witnessed not only by his many endowments of dioceses but also the building spree, which he was responsible for, mark his reign.

One such project was his planned rebuilding in Goslar of both palace and the cathedral. Though heavily rebuilt, the palace still stands as evidence of the importance of the nearby silver mines. A parallel foundation (a so-called “Pfalsztift”) was built at Kaiserswerth (1045) on the river Rhine, now part of Düsseldorf. Another project supported by Henry was the on-going construction of the Cathedral in Speyer, and the family vault for the Salians. A third important city was Nuremberg, which, founded at the turn of the millennium, is mentioned for the first time in a document from 1050. Nuremberg was later to become the “unofficial capital” of the Holy Roman Empire. Apart from Goslar, Henry III may have supported few religious institutions like abbeys or convents. But this clouds the fact that his effort primarily was channelled into supporting his network of bishops and through them, their joint investment in the new and spectacular Romanesque churches, which came to define Germany in the 11th century.

Early Romanesque Speyer

Most spectacular of these cathedrals was Speyer. Until the 11th century, the building of a church was not that technically complicated. The common form were halls with the walls construed by rough masonry and simple mortar; these would be covered with lime plaster and painted with frescos. The main effort would be channelled into the magnificent furniture and vestments: chandeliers, baptismal fonts, golden altars, liturgical vessels and vestments of luxurious silks. With a start on the new cathedral in Paderborn in 1009, followed by Strasbourg in 1015 and St. Michael in Hildesheim consecrated the same year. Later, the rebuilt abbey church in Echternach is a fine reminder of this early building spree, which was crowned with the splendid project in Speyer, initiated by Conrad c. 1030. This cathedral was intended as the burial ground for the Saliens, and indeed eight kings and emperors plus some queens came to be buried there, beginning with the parents of Henry III, Conrad II and Gisela. Today, Speyer looks differently than in the days of Henry III. With Romanesque vaults commissioned by his son, it stands perhaps more impressive than in the time of Henry III. Nevertheless, the Cathedral in Speyer remains one of the most significant testimonies to the importance of the new architecture and art of stone-carving, called the Romanesque.

Bishops and Towns

Privileges confirming the rights of citizens to convene freely and establish guilds were a necessary precondition for further growth. Part of this was also the gradual institution of law and order enabled by the appointment of diocesan administrators and educated church officials. Gradually, judiciaries with authority to adjudicate cases between non-nobles and nobles came to be (at least partially) instituted. Although much of this did not grow to fruition until later in the 12th century, occasional glimpses of the growing importance of towns as free trading centres are found. Instrumental in this were the bishops as was, for instance, the case in Paderborn. Here bishop Meinwerk is known for his extensive rebuilding of the palace and the cathedral and other churches. Gradually Paderborn grew into a proper town. Another example of this is Goslar, which began as a hunting lodge but was rebuilt as a magnificent royal and ecclesiastical complex later in the 11th century. Undoubtedly, this fostered the first suburban settlement, which archaeologists have dated to the 1040s. But the royal confirmation or at least blessing seems to have been important. Bishops, who fell foul of the king (as happened at Cambrai) had to give way to the local count.

Peace and Truce of God

In this project, the theology behind the institution of “The Peace and Truce of God” (pax Dei and treuga Dei) came to play a substantial role. In a world marked by excessive comital powers, castle building and feuding, rebelling and rampant violence had gradually reached its apogee around 1000 CE. The instrument used to quell this violent culture was proclamations issued by first local clergy, and later leading churchmen, designating specific spaces and times, where and when feuding was declared illegal under the threat of excommunication. Later, kings came to play a significant role in supporting this movement. Thus, in October 1043, Henry III during a synod in Constance stepped up to the altar in the Cathedral and preached a sermon, admonishing his people to preserve the peace. He is also said to have issued a royal edict mandating a “peace such as had not been seen for many centuries” [i]; claimed to be one of the first royal interventions or orders of this kind. At this time, “the idea of Henry III as a Christ-like king and an emperor of universal peace kept gaining its own momentum”, writes Weinfurter, mentioning the fact that Henry III was also the first to decree that anyone, defying him or showing contempt for him, were to suffer the death penalty. In no way did Henry III think of himself as primus inter pares.

Undoubtedly, part of the inspiration to his involvement in this peace process came from his wife, Agnes, and her close affinity to Cluny. Founded in 910 by her ancestors, the Dukes of Aquitaine, it served as the hotspot of the religious reform movement of the 11th century. It is significant that both the cardinal, Petrus Damian, and the abbot, Hugo of Cluny, featured as god-parents to the future Henry IV. Supported by Henri III, they became instrumental in the burgeoning reformation movement battling simony and – later – royal investiture through their support of popes like Leo IX, and his heirs, Alexander II and Gregor VII. The years from 1044 – 46 marked a serious crisis for the papacy with three Roman parties fighting for the power to appoint the next Pope. Simony played a significant role in these machinations, and when Henry III arrived in Rome for the imperial coronation, he had his close collaborator and friend, Bishop Suidger of Bamberg elevated as Clemens II. Followed by a number of reformist popes from Germany, Leo IX (1048 – 1053) deserves to be especially noted as one of the more prominent. As friend and tutor of the future Gregory VII, Leo worked to combat simony and later lay investiture, laying the ground for the conflicts between Pope and Emperor, which came to mar the reign of Henry IV later in the 11th century. During the reign of Henry III, the close collaboration between church and state was secure. With numerous bishops appointed from the staff of the royal chapel, the emperor built a loyal network of friends placed in central hubs throughout the kingdom.

Royal Ethos

However, the focus on the king as peacekeeping officer par excellence was drummed into him at an early date. One of the chaplains to Conrad II was Wipo of Burgundy (c. 995 – 1048). Already in 1028, Wipo had presented a “mirror” to the prince, the Proverbia, on the eve of his coronation in Aachen[2]. With hundred verses the aim was to outline the moral foundation for the future reign of the young king.

Through these, he would be taught that:

- It is better to lower than elevate oneself – meliesus est se humiliare quam exaltare

- Where there is true penitence, there is also the grace of God – Ubie est vera penitentia, ibi Dei clementia

- Who is merciful, will be shown mercy –

Qui miseretur, misericordiam consequetur

Later Wipo wrote a biography in chronicle form of Conrad II: Gesta Chuonradi II imperatoris, as well as a didactic tract, the Tetralogus Heinrici. In rhymed hexameters this treatise exhorted the king (and future emperor) to devote his reign to further a general (global) peace; this he ought to insist upon by nourishing a lawful society steeped in mercy and grace. Probably from Wipo, Henry got the idea, that just as David was the precursor of Christ, so was Henry III as anointed king and emperor, the closest approximation to a living Christ. Neither the Pope nor the Holy Catholic Church received a mention in the Tetralogus!

Later, this led to the Emperor to not only participate in traditional imperial processions, but also staging particular performances of penitence; such as when he at the funeral of his mother in 1043, discarded his royal attire, dressed in the sackcloth of the penitent, and threw himself onto the ground with his arms outstretched, while weeping profusely (as recorded by Berno of Reichenau) [3]. Henry III had obviously had his controversies with his mother; now through a public act, but as a private person, he carried out his act of attrition; But he was also king of the realm. The penitential act reverberated throughout the kingdom, raising expectations in some quarters and irritation in others. At the end of his reign, this led a cardinal to criticise him widely for hypocrisy and greed. [4]

It is perhaps fitting that when he was finely laid to rest in Speyer, he was clad in sumptuous silken hoses coloured in deep red and blue. [5]

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The Salian Century: Main Currents in an Age of Transition. By Stefan Weinfurter, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, p. 101 ff.

[2] Scriptores Rerum Germanicarum in usum Scholarum ex Monumentis Germaniae Historicus separatism editi. Wiponis Opera. Ed. by Harry Bresslau. Editio tertia. Hannover and Leipzig 1915

[3] Die Briefe des Abtes Bern von Reichenau. Ed. Franz-Joseph Schmale. Series: Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für geschichtliche Landeskunde in Baden-Wurttemberg, Series A, Vol. 6, Stuttgart 1961, app. 24

[4] Königsherrschaft und Gottes Gnade: Zu Kontext und Funktion sakraler Vorstellungen in Historiographie und Bildzeugnissen der ottonisch-frühsalischen Zeit. By Ludger Körntgen. Oldenburg Verlag 2001.

[5] Des Keisers letzte Kleider. Neue Forschungen zu den organischen Funden aus den Hersrchergräbern im Dom zu Speyer. Ed. by: Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer. Minerva 2011.

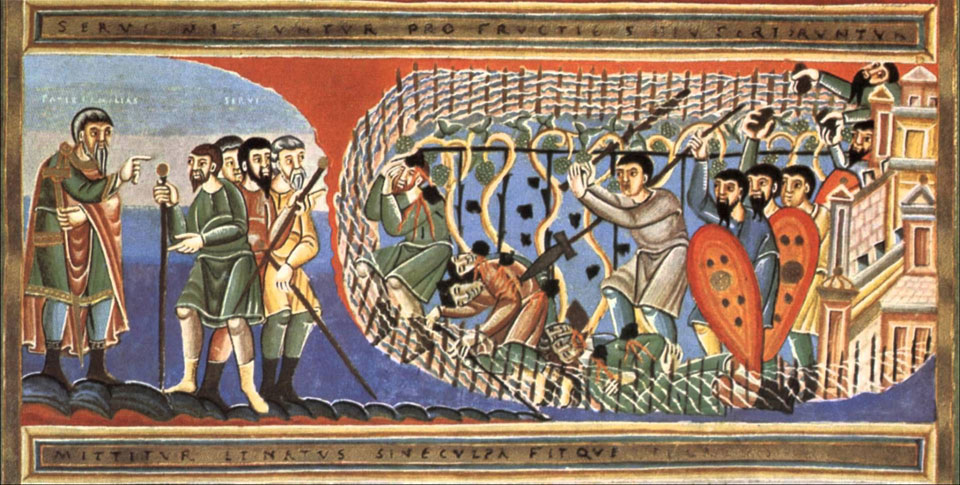

FEATURED PHOTO:

Henry III and Agnes from the Evangeliary from Speyer (Codex Aureus Spirensis) El Escorial, Real Biblioteca, Cod. Vitrinas 17. Source: Wikipedia

SOURCES:

Save