Henry III may be remembered as a pious emperor, dedicated to uphold a new vision of rulers as handmaidens of the church. But he was also steeped in traditional ways of enacting justice as the story of his feud with the Billungs tells us.

Verdicts of Henry III (1016 – 1056), King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor from 1039 tend to focus on his renowned piety, his semi-clerical status and his active engagement in religious politics of his day: the schismatic papacy, the ecclesiastical reform movement, and the peace movement.

The fact remains, though, that Henry III was also a belligerent king involved in numerous campaigns in Poland, Bohemia and Hungary. What is perhaps less well known are the numerous rebellions he, as opposed to his son, successfully negotiated or fought his way out of. One of these revolts, the Billungs, dukes of Saxony, initiated

After the Saxon dukes, the Liudolfings were elected kings of Germany in the 10th century, and the Billungs were entrusted with the control of the duchy. Later, their position solidified, and they rose to be dukes. As such, they were powerful magnates ruling over the north and northeast of the empire when Henry III came to power in 1039. At some point in time, the Billungs were even recognised as Counts of Frisia. At the end of the reign of Henry’s father, Conrad II, the emperor had nevertheless, confiscated some valuable land north of Bremen around the river Lesum and dedicated it to the income of his queen, Gisela.

During the reign of Henry III, the ruling Duke was Bernard II. In 1047, the Archbishop of Bremen asked the Emperor to come to Bremen to meet up with the new Danish king, Sweyn II Estridsen, a cousin to the first wife of the emperor and a potential ally (or foe). According to the Chronicle by Adam of Bremen, the reason was, however, primarily to “test” the fidelity of the Dukes. At the river Lesum, north of Bremen, the brother of the Duke, Thietmar, ambushed the Emperor. Henry, however, overcame the attack and later, Thietmar was summoned to court, where his vassals accused him of having plotted to kill the Emperor. Thietmar chose to defend himself by single combat, but unfortunately he died of his wounds. A few days later, we learn, the other combatant, Arnold, who had represented the emperor, was apprehended by the son of Thietmar, and hung up in a tree by his ankles “between two dogs”. After this, the son was captured and sent to life-long exile by the emperor, while his land was forfeited. This led the Duke to pursue the Archbishop of Bremen with mortal hate, writes Adam.

Borghorst

It is highly likely that the convent in Borghorst belonged to these possessions of land or interests. From the studies, carried out by Gerd Althoff on the Necrology we know that abbesses at Borghorst belonged to the Billungs and also that the last Billung listed in the necrology was the same Thietmar, who had died in Bremen. After this, the necrology concentrated on the emperor and his network.

In this connection, it is worth studying one of the absolute treasures from the time of Henry III, the Borghorst Reliquary Cross. 41 cm in length and 24.4 cm wide, it is made of a wooden core plated with gold on the front and with copper on the back. Numerous gems, rhinestones, and silver pearls embellish the front. In the midst are three hollow crystals, of which two are Fatimid flasks. These hold relics wrapped in red silk. On a lower panel, where donor-portraits are usually positioned, we find a gold plate in relief showing a crowned king raising his arms towards two angels attempting to lift him up. Heinricus, we are told, is the name of the donor. On the back of the cross, we meet Bertha, abbess at Borghorst praying. In all likelihood, the beautiful crucifix was gifted to the Abbey as an act of reconciliation, when Henry III was introduced to Borghorst as its new patron.

It is believed that the artist, who made the crucifix, also designed the cover to the so-called Theophanu Evangeliary. Studies of pollen in the wax used as the base for the gold plate reliefs have shown that both pieces of art stem from the same workshop in Essen. This cover was donated by the Abbess Theophanu (997 -1059) to the diocese in Essen as part of a valuable treasure consisting of a new evangeliary, a bejewelled crucifix and a reliquary containing one of the four nails. Theophanu was a daughter of Ezzo, Duke of Lorraine, and granddaughter of Emperor Otto II. She was named after her grandmother, a princess from Byzantium. Theophanu, the Abbess, was active in Essen, where she was responsible for rebuilding the Cathedral, setting down the privileges for the city market, and the donation of the treasures for the new church. In all probability, she was also responsible for the erection of a chapel in the marketplace, consecrated to St. Gertrud.

Some art historians believe that the cross was at first a gift to Essen made by Henry III. Later a new backside of the crucifix was fitted to it, featuring the incised drawing of Bertha and turning the cross-reliquary into a gift witnessing to the reconciliation between Henry and the Billungs.

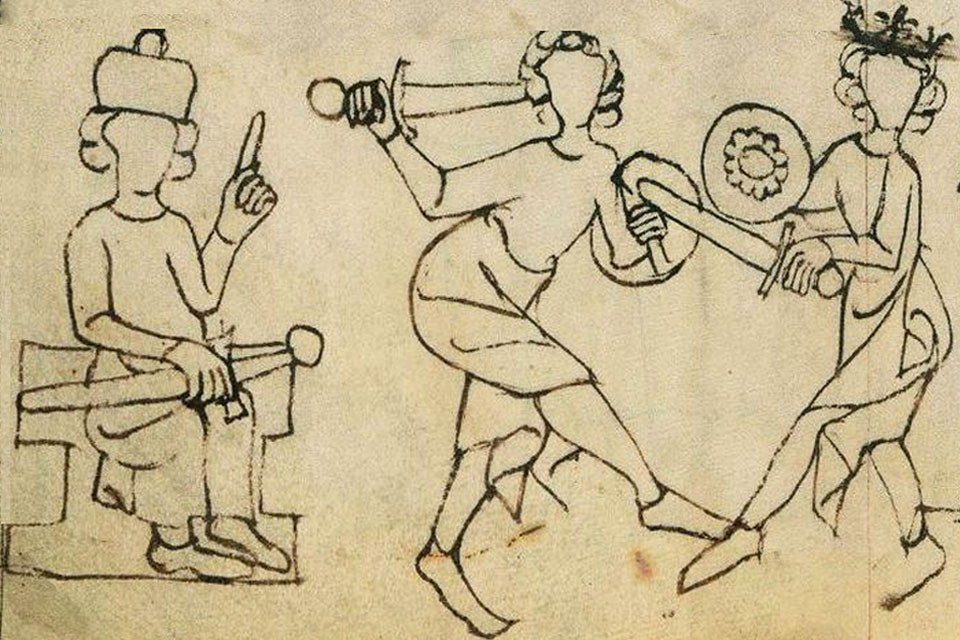

FEATURED PHOTO:

Trial by combat. From: Sachsenspiegel from Oldenburg, c. 1220 (manuscript 1340), fol 63 V. Source: Landesbibliothek Oldenburg

SOURCE:

Königsherrschaft und Konfliktbewältigung im 10. und 11. Jahrhundert.

By Gerd Althoff

In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien (1989) Volume 23, Pages 265–290.

Das Herzogtum der Billunger – ein sächsischer Sonderweg?

Hans-Werner Goetz

In: Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte. Verlag Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover (1994) Vol 66, pp. 167 – 199

READ MORE:

By Anne Kurtze

Michael Imhof Verlag 2017

ISBN: 978-3-7319-0302-4

READ ALSO:

Save

Save

Save