Architecture identifies Gothic Style. Just think of breath-taking cathedrals, mounting pillars, soaring vaults. It pays, though, to think of it as the physical expression of a special theological motive, the transgressing soul climbing through the Heavens. As such, it marked a plethora of other – minor – art forms.

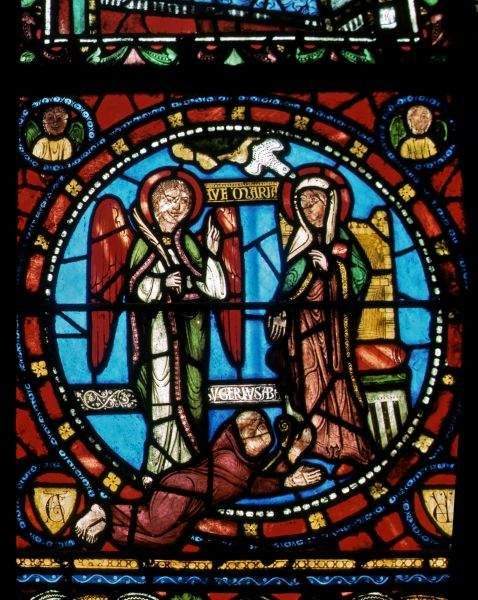

Gothic architecture was the predominant art-form in 13th–15th century Europe. It arose in the early 12th century out of the attempts of the medieval builder to lift massive masonry vaults over wide spans without causing the downward and outward pressures threatening to collapse the walls in an outward movement – such as happened in 1284 at Beauvais, when some of the vaultings in the choir fell causing an uproar in the international guild of masons; and perhaps, a turn towards less spectacular building projects. The significant constructional element in this new and innovative way of building large monuments was the invention of the ribbed vault, which was first applied in the rebuilding of the Cathedral of St. Denis in 1140, which was planned and carried out by the abbot, Suger. With its dispersion of the weight to the ribs, these might be supported by pillars and piers, which would replace the continuous thick walls. In between the pillars, light could be channelled through the impressive windows, graciously decorated with elaborately stained glass. The primary example of this – the Rayonnant or decorated Gothic style – is the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. With its jewel-like character, it seems to enshrine the visitor together with its most famous relic, the Crown of Thorns. Later, the style became even more flamboyant. We know this from numerous town- and guild-halls from the 15th century.

However, Gothic cathedrals and later chapels were just one of the many Gothic pieces of art, which came to dominate the period. Reliquaries, altars, retables, tombs, fonts, pulpits, stalls, sculptures, ivories, manuscript covers and paintings as well as textiles all came to represent a kind of “micro-architecture”, typically featuring scenes framed or traced by pillars, buttresses and ribbed vaults.

Albeit these obejcts appear to have always been based on strict geometry, deft implementation of optical and colouristic elements overcame this, in the creation of micro-worlds or spectacles, inhabited by people gripped by all the spectres of emotion as may be seen in the famous Reliquary of the Holy Sepulchre from Pamplona.

We know from contracts that a dividing line was seldom drawn between metalwork, carpentry, and construction. This furthered dissemination of the artistic ideas from France and outwards to the peripheries to the north and east. As did the use of architectural drawing on parchement.

Gradually, through this diffusion of minor decorative pieces of art, Gothic also came to represent a particular idea of how to dress and comport yourself in gliding vertical movements enshrined in the tableaus of the courtly romances depicted on ivory caskets, jewellery and other objects of art.

In the end, the Gothic style gave away to the Renaissance, known to have designated the art form as precisely “Gothic”, that is quaint and barbarous.

The Idea of the Gothic

To some extent, Gothic Art is paradoxical. Its central expression was its architecture, yet the new and soaring monuments with their ribbed vaults supported by elegant pillars and piers were in clear opposition to the cultural climate of the 12thcentury renaissance. With its revival of Aristotelian logic, Roman law, Latin prose and poetry and Ciceronian writings, one should have imagined an accompanying resurgence of classicist architecture.

As is well known, however, this did not happen. Gothic Cathedrals do not look anything like Roman temples, albeit the sculptural embellishments of the same buildings – not least in the portals – to some extent did reinvent the idea of Roman portraiture. Instead, Gothic architecture and style exploded onto the art scene with an avant-garde force that continues to awe us.

What went on? First must be noted that these buildings constituted “Gesamtkunstwerke” to an extent never seen before. With their fabulous architecture, impressive portals, magnificent sculptural decoration, livid paintings and polyphonic music, the cathdrals invited the lay churchgoer to experience them in their totality. Moving further inside – as a liturgist or semi-clerical lay-person – the cathedrals and churches would open up to reveal reliquaries and other minor art-forms exhibited on the altar and presented as micro-architecture. It is obvious this glittering world came to entice people with a spiritual message encoded in the dramatic pageant of the mystery and miracle plays. We should remember that the early Gothic period culminated in the early 13th century Franciscan movement, with its pervasive use of pageants, including the first “live” Christmas crib” at Greccio.

As such, the beautiful Gothic churches were not primarily symbolic or allegorical installations as much as they were anagogical invitations for the viewers to be lifted up – whether by colour and light as Suger experienced it. Or as St. Francis found by way of nature.

Patrons were inspired by the idea of the temple of Solomon, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, or the New Jerusalem and its “descent from heaven”, while architects may have considered vaults as symbols of the baldachins covering the holy grave of the altar on which the Eucharist was celebrated. Symbolism and its handmaiden, allegory, did play substantial roles in the planning of the new churches. But the central perspective was, without doubt, the sublime spiritual ascension of the soul towards the heavens, that is: the trascendal movement.

Here, subtle symbolism did not aid as much as teaching through experience – hence the widening use of architecture as spatial organisation of processional with its inbuilt eastward and upward directions, as well as the constructions of tableaus in the liturgy, paintings, mystery plays, and monumental as well as miniaturist sculpture.

The latter may be what we conjure up as the idea of the Gothic. Here the massive portals at Chartres, Reims, and Regensburg come to mind; as does the west choir of Naumburg Cathedral with the breathtaking donor portraits from c. 1245 – 1250. As does the minaturist sculptures forged in golden reliquary shrines. Thus, while we may identify Gothic Art with cathedrals like those of St. Denis and later Reims, Amiens, Bourges, Chartres, Beauvais, Lincoln, Westminster and Cologn, Gothic aesthetics was probably more widely available to medieval people in the numerous pieces of minor decorative art-forms as well as in the literary renditions, found in poetry and novels in the later Middle Ages. We may think of the phantasmagoria of the quest for the grail, and the imaginary temples erected to hide it from the unjustified. But also the rendition of the Heavenly Jerusalem in liturgies as well as in later poetry, like The Pearl. Or in the new polyphonic music in Paris. Another genre, Gothic in its inner core, were mysterious writings like “the Cloud of unknowing”; literally offering a way into the mysterious “beyond” through contemplation, ascension, and finally transcendence, transformation and revelation.

To conclude: Gothic was not just a new style of art. It was the formal expression of a way of thinking about humans on quests reaching beyond – to the Holy Land on a Crusade or up towards Heavens. The latter came to be envisioned as a sculptured procession of jamb statues, as well as spatially indicated by routes though the Gothic Cathedral towards the central and most mysterious act, the transubstantiation of the Eucharist at the high altar. Later, this gave the impetus to the development of the elaborate Sacrament Houses, those dazzling and complex microarchitectural structures designed for the preservation and display of the”real present” body of Christ.

Gothic Art – more than just a single idea

The distinct characteristic of the early Gothic Cathedrals – the preoccupation with light infusing the inner sanctum – led the famous art historian Erwin Panofsky to publish two significant works on Gothic Art. In 1946 he published his work on Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its art treasures. Based on the Norman Wait Harris lectures delivered at Northwestern University in 1938, his book on Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism followed in 1951.

In these two slender books, Panofsky outlined the complexities of how to understand Gothic Cathedrals. He did this by what later art historians have often thought of as overreaching the evidence. As Panofsky saw it, the early work of the patron Suger was to set into motion the construction of an edifice embodying the neo-platonic fusion of materiality and light.

In its classical form, this is what the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu later came to define as a “field” – a space, where no single type of cultural capital has a monopoly, and therefore a space constituted by the interplay and competition between intermingling ideas. Bourdieu later wrote in a postscript to his translation into French of the second of these books, how he was inspired by Panofsky’s writings on Gothic Architecture when outlining his distinctive sociological field-theory. Through his essay, Bourdieu helped to publicly ground the work of Panofsky at the centre of the European Philosophical debates peopled by – among many others – Cassirer and later Heidegger, a perspective which the Anglophone world, in which he found his home in the 1930s, not always seem to have appreciated. Later, Pierre Bourdieu used this as the point of departure for his book on “The Rules of Art”.

The point was of course that the idea of the Gothic was never just monolithic. It was fundamentally constituted by the interplay between two opposing forms of “capital” – spirituality and materiality. With the former primarily “seen” as light and voiced in theological treatises and sermons, the latter consisted of the practicalities of wielding masonry to support the effusion of the former. Hence, Panofsky came to write about the hidden or underlying rationality of the buildings as based on careful mathematical and geometrical – scientific – calculations. Not for nothing, the 12th-century Renaissance was also the time of the rediscovery of the work of Ptolemy translated into Latin in 1170, as well as the adoption or import of the astrolabe. Albeit classical works and inventions, both had overwintered in the Arab world, until they reentered Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries.

In a more practical historical context, this led later art historians, primarily Peter Kidson, to view the work of Erwin Panofsky as severely curtailed. As Kidson formulated it, if Suger was the patron, who was the architect? And how did this ephemeral person go about his work, if not as a mathematician and a scientist? And what about the practicalities of quarrying and cutting the stones? The material aspect of the whole enterprise?

Today, we know much more about the practicalities of planning, drawing, and building these magnificent Cathedrals than at the time, Panofsky wrote his groundbreaking works. With the help of radar, sonar, and perhaps even lidar, scientific investigations of the structure of buildings have moved significantly forward. And, thanks to Bourdieu, we know how to grasp the intricacies of the medieval world of interlocked and competing types of cultural capital in the 12th century – spirituality versus materiality. Or as Panofsky described it, as “the task of writing a permanent peace treatyr between faith and reason” [1]

NOTES:

[1] Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism: An Inquiry into the analogy of the arts, philosophy, and religion on the Middle Ages. By Erwin Panofsky (1951). Meridian Books 1976, pp. 28 – 29.

SOURCES:

Panofsky, Suger, and St. Denis

By Peter Kidson

In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes (1987), Vol 50, pp. 1 – 17

Architecture and the Visual Arts

By Peter Kidson

In: New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol IV, No 1, pp. 693 – 731

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Peirce, Panofsky, and the Gothic

By David Wagner

Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society

Vol. 48, No. 4 (Fall 2012), pp. 436-455

Bourdieu and the Art Historians

By Richard Hooker, Dominic Paterson, and Paul Stirton

In: The Sociological Review (2001), Vol 49, No 1, pp. 212 – 228

MAIN RESOURCE:

With a database of images, texts, charts and historical maps, Mapping Gothic France invites you to explore the parallel stories of Gothic architecture and the formation of France in the 12th and 13th centuries, considered in three dimensions: space, time, and narrative.

SEE MORE:

READ MORE:

The Work of Erwin Panofsky, Peter Kiddon, and Pierre Bourdieu

General Introductions:

Special Studies: