In the 19th century, the public became aware of a treasure trove of more than 280.000 Jewish manuscripts carefully “buried” in the Cairo Genizah of the Ben Ezra Synagogue. Since then, the invaluable collection has shed light on the Life-worlds, worldviews and religious thoughts of Middle Eastern Jews reaching back more than 1000 years.

From the 9th to the 19th century, the Jewish community of Fustat (Old Cairo) deposited at least 280.000 old and obsolete writings in a purpose-built storeroom in the Ben Ezra synagogue. Genizah in Hebrew means a hiding place. Such Genizot can be found in all synagogues and are intended to preserve any scrap of paper on which may is written the word “God”. Sacred, such pieces of paper or parchment were – and are – considered too holy to discard. Eventually, such holy writings were intended for burial in the cemetery. Occasionally, though, this fate eluded these collections; as was the case with the treasures in the Caito Genizah.

From the 9th to the 19th century, the Jewish community of Fustat (Old Cairo) deposited at least 280.000 old and obsolete writings in a purpose-built storeroom in the Ben Ezra synagogue. Genizah in Hebrew means a hiding place. Such Genizot can be found in all synagogues and are intended to preserve any scrap of paper on which may is written the word “God”. Sacred, such pieces of paper or parchment were – and are – considered too holy to discard. Eventually, such holy writings were intended for burial in the cemetery. Occasionally, though, this fate eluded these collections; as was the case with the treasures in the Caito Genizah.

The Cairo Genizah came into being between 1025 – 1140, when the Ben Ezra Synagogue was rebuilt after its destruction in 1012 at the instigation of the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah. However, the Synagogue is believed to have been around before Islamic times, and some papers from the old Genizah found their way into the new building, which incorporated an unusual large store-room: two stories high, more silo than attic and accessible only from above through a rooftop opening.

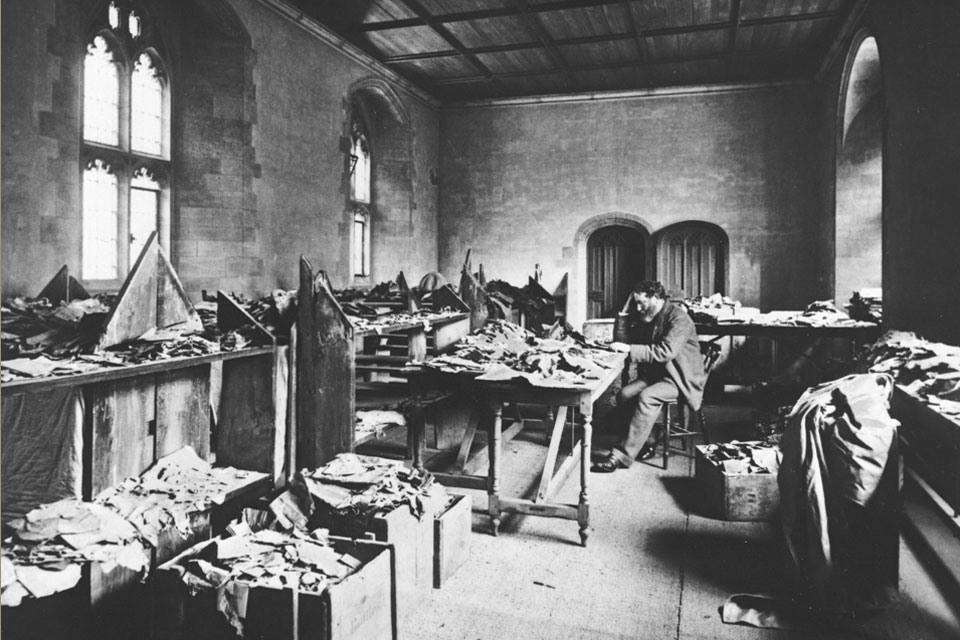

In 1753, a German antiquarian and traveller, Simon van Geldern, was the first to report about the Cairo Geniza. To his chagrin, though, he was not allowed to inspect the treasure trove. Later, in the mid-19th century, another Jewish writer spent several days in the store room until he got sick from the dust and ashes. Now, collectors and scholars began to ferret out treasures. This culminated in 1889 when the old storeroom was rediscovered in connection with a renovation of the synagogue. Needing funds for the building work, the Elders proceeded to sell several significant caches. The major haul, though, did not take place until Solomon Schechter, Professor at Cambridge, became obvious of a page from the text of Ben Sira from the collection. Ben Sira was until then only known in a Greek translation, which had been accepted into the Christian Canon and was known as Ecclesiasticus. Finally, in 1896, Schechter travelled to Cairo, where he succeeded in acquiring the rest of the hoard and bring it back to Cambridge. Since then numerous Hebrew scholars, theologians, historians, and conservationists have worked tirelessly to catalogue, study, and restore the priceless fragments. Today, the Taylor-Schechter Collection at Cambridge holds the largest part, 193.000 fragments. However, substantial collections can be found in Oxford, Manchester, and New York.

Religion, Language, and Social Life

It stands to reason that numerous fragments are of primarily theological and religious significance. Even though utmost care was taken to verbatim preserve religious texts, corrections, misunderstandings and rewritings would occur, demanding a comparative perspective on the texts. However, many “minor” texts were also written in Aramaic, using the Hebrew language, offering up opportunities to study shifts in the use of language. As many texts also have the status of witnesses – wedding contracts, divorce deeds, charters, affidavits, other court documents and legal writings, and sales agreements, they also witness to the multilingual and multicultural society of Cairo during Muslim and Arabic rule. To these more formal documents must be added such curiosa as shopping lists, a page with doodles and alphabets of a child, Arabic fables, works of Muslim philosophy, medical books, magical amulets, business letters and accounts. The texts from 950 – 1250 are in this context considered unique and invaluable and have resulted in numerous monographs telling the story of Life in Cairo in the High Middle Ages.

According to the head Head of the Genizah Research Unit, Dr Ben Outhwaite, the Genizah collection does not offer “a broad brush picture of the medieval Middle East as a crucible of cruel oppression”. Neither, he claims, is it “an interfaith utopia”. Both these renderings do not do “justice to the eye-level history recorded in these sources. Life, for the culturally rich and socially conscious citizens of the medieval Middle East, was more complicated, sophisticated and interesting than that,” he adds.

Maimonides 1135–1204

Some of the most precious items are the handwritten, autographic documents from the hand of the Jewish philosopher and scholar, Maimonides and his sons. They shed light on the cultural and religious context in which the Ramban wrote his universally beloved “Guide for the Perplexed”.

We are also able to discern how he concretely plied the law as outlined in his fourteen-volume Mishneh Torah, a codification of Talmudic law. Originally a Sephardic Jew, he was expelled from Cordova in 1135. After a sojourn in Morocco, he went to Cairo, where he lived near the Ben Ezra synagogue and worked as a physician at the court of the Sultan. Although he did not worship at this Synagogue, pieces of his autographed writing ended up in the Genizah, for instance, the famous text, in which he describes his sorrow over the death of his brother, who drowned on a merchant ship in the Indian Ocean.

At least 376 documents or fragments thereof from the collection witness to the work of Maimonides.

“The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint, may his memory be blessed, who drowned in the Indian sea, carrying much money belonging to me, him, and to others, and left with me a little daughter and a widow. On the day I received that terrible news, I fell ill and remained in bed for about a year, suffering from a sore boil, fever, and depression, and was almost given up. About eight years have passed, but I am still mourning and unable to accept consolation. And how should I console myself? He grew up on my knees; he was my brother, [and] he was my student.” (Maimonides)

From: Letters of Medieval Jewish Traders. By S. D Goitein. Princeton University Press 1973, p. 207.

Discarded History

This spring, The Cambridge University Library has mounted an exhibition of some of the more prominent treasures in the Genizah Collection. Called Discarded History, it exhibits treasures like the earliest known example of a Jewish engagement deed (Shtar Shiddukhin, from 1119), the oldest-dated medieval Hebrew manuscript (a Bible from 9th century Iran) and an 11th century pre-nuptial agreement, where the groom, Toviyya – who clearly had a bad reputation – was forced to make a series of promises about his future behaviour.

“This colossal haul of writings reveals an intimate portrait of life in a Jewish community that was international in outlook, multicultural in make-up and devout to its core; a community concerned with the very things to which humanity has looked for much of its existence: love, sex and marriage, money and business, and ultimately death, says Dr Ben Outhwaite. He continues to explain that “The Genizah collection undeniably is one of the greatest treasures among the world-class collections at Cambridge University Library. We have translated most of these texts into English for the first time – and most are also going on display for the first time, too. With Discarded History, we hope to make this medieval society accessible and recognisable to a modern audience.”

VISIT:

Discarded History: The Genizah of Medieval Cairo

Milstein Exhibition Centre, Cambridge University Library West Rd, Cambridge, UK

27.04.2017 – 28.10.2017

SOURCES:

Discarded History: The Genizah of Medieval Cairo (press release)

Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit. Cambridge University Library, Special Collections.

READ MORE: