During the 4th-8th century, vast stretches of Europe shifted from growing wheat to rye. Careful studies indicate the shift was a reflection towards a new, more balanced peasant economy.

Numerous studies of pollen records show that the intensive growing of wheat during the Roman optimum was widely superseded by the adoption of rye. Did climatic changes cause this shift? Were ethnic migrations responsible? Or was the shift caused by a structural adaption of peasants to a new market structure and living situation?

The Shift

During the Roman Optimum, the cities and armies required extensive and substantive supplies of grain and foodstuff. Much was furnished from Egypt, Northern Africa and Sicily in the form of wheat. Other regions provided olive oil, quick peas and other stables securing the possibility to enjoy the same typical Roman fare from Vindolandum at Hadrian’s Wall and into the deep south.

However, while Rome declined and fell, so did the army. With this decline, the “Roman” diet changed fundamentally together with the agricultural system. From a “market” orientation to a more local system geared towards self-subsistence and a more pastoral economy, the profile of typical agricultural products changed: from large animals to smaller, from cattle to sheep and pigs, from wheat to rye. At the same time, a decided retreat from the late antique fields with fodder crops like lucerne, or alfalfa took place. Formerly these plants were a favourite feed of Roman cattle and horses; now they were less in demand because of the lack of demands from the army and its cavalry, creating an overall shift towards a pastoral economy. Also, the period saw the introduction of the chestnut in Southern Europe. What caused these shifts?

Why not the climate?

It is a well-known fact that Europe in the 6th century suffered from a prolonged series of climatic disasters forced by at least three volcanic eruptions on an extraordinary massive scale (AD 536-42). And that these disasters led to a severe cooling of the average temperature as well as accompanying challenges of erosion, deposition and flooding. In northern Europe, the growing season foreshortened, as did the limits of cultivation in terms of elevation.

Repeatedly, it has been suggested that the shift from wheat to rye reflected this climatic deterioration. Unfortunately, this explanation does not seem to fit the facts.

For instance, studies of the agricultural shifts in Northeastern Gaul indicate that the growing of rye came to play an important role even though the climatic shifts there, were minor compared to what was the case further north in Scandinavia.

Why not a question of ethnicity?

This fact has led to another favourite explanation, that of ethnicity. Might the introduction of rye be a “Barbarian” import following the migratory movements in Late Antiquity? Arguably, Northeastern Gaul was taken over by the Franks in the 4th – 6th century and cultivation of rye might reflect their dietary predilection?

Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case. At the same time as the Franks settled up north in Gaul, the Visigoths settled in Aquitaine. There, however, the shift was never marked. At the same time, and without suffering from migratory “invasions”, the peasants in Sicily adopted rye. An ethnic explanation does not seem to fit the facts, write Squatriti.

A new deployment of the workforce?

Contrary to this, Sqautriti explains the adoption of rye with its labour-extensive qualities. Like the chestnut, it fitted well within in a context where labour resources were lacking.

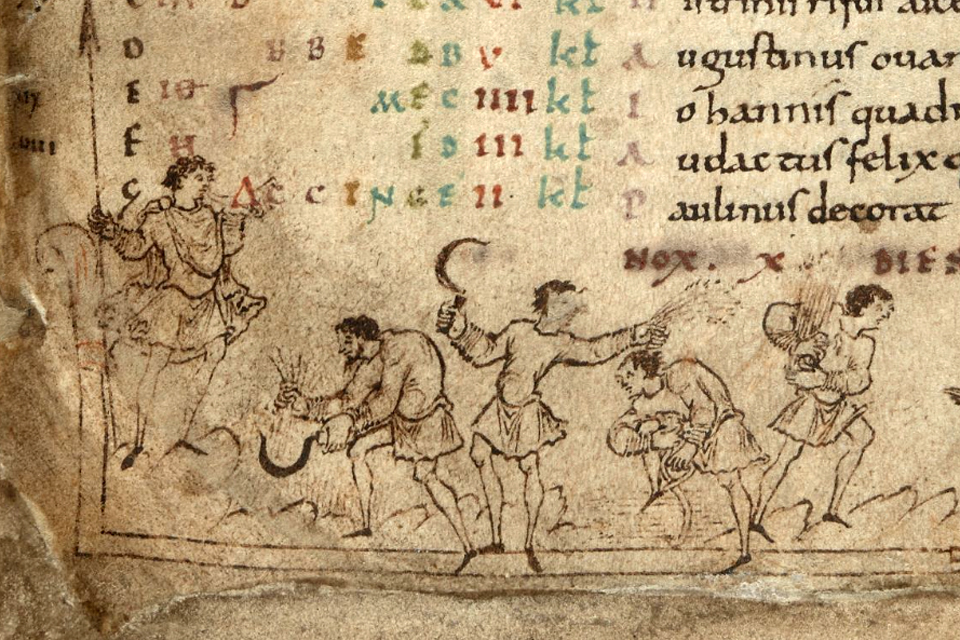

“As a mostly winter-sown grain”, rye fitted comfortably into farming calendars and allowed for a more even distribution of the work effort and rendered an early output, Writes Squatriti. It can be sown in late autumn as the seed germinates best after having felt a freeze. Thus, this work can be scheduled at a time when the number of chores is otherwise whittled down. With the prospect of harvests in June-July, it helps to soften the lack of victuals before harvest time in August. Also, though harvesters had to stoop low with sickles, they had the double gain of preserving stalks for roofing and a crop which was easier to cart from the field; and a grain which only needed light threshing as opposed to the “hulled” grains, which had to be forcibly separated from their husks. Rye also took up less space, because it was easier to preserve in smaller dedicated vessels or containers than corn still on the husk.

Rye, then, offered a solution to the peasants in the Early Middle Ages. Arguably, white, wheaten bread continued to be the preferred favourite of the literate and the elite. But rye’s ability to leaven with sourdough (as opposed to barley) secured it a step up the ladder from plain porridge. Foremost, though, it offered a better organisation of chores by spreading them out across the full year.

Nonetheless, it took until the 21st century to make ryebread an elite delicatessen. In Late Antiquity, it was considered a sign of asceticism or rough peasant fare.

From there, in decorous manner, she approached the villa of Saix near the aforesaid town in the territory of Poitiers, her journey ever prospering. Who could recount the countless remarkable things she did there or grasp the special quality of each one? At table she secretly chewed rye or barley bread which she had hidden under a cake to escape notice. For from the time she was veiled, consecrated by Saint Médard, even in illness, she ate nothing but legumes and green vegetables: not fruit nor fish nor eggs. And she drank no drink but honeyed water or perry [cider made from pears] and would touch no undiluted wine nor any decoction of mead or fermented beer. Then, emulating Saint Germanus’ custom, she secretly had a millstone brought to her. Throughout the whole of Quadragesima, she ground fresh flour with her own hands. She continuously distributed each offering to local religious communities, in the amount needed for the meal taken every four days. With that holy woman, acts of mercy were no fewer than the crowds who pressed her; as there was no shortage of those who asked, so was there no shortage in what she gave so that, wonderfully, they could all be satisfied. Where did the exile get such wealth? Whence came the pilgrim’s riches?

Venantius Fortunatus: Life of St. Radegund (520-587)

Quoted from : Sainted Women of the Dark Ages. Jo Ann McNamara, John E. Halborg, with E. Gordon Whatley. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1992), pp.70-86, chapter 15.

SOURCE:

Rye’s Rise and Rome’s Fall: Agriculture and Climate in Europe during Late Antiquity

By Paolo Squatriti

In: Environment and Society in the Long Late Antiquity

Ed. by Adam Izdebski and Michael Mulryan

Brill 2019