1300 bones have been picked to create order out of chaos in the famous bone caskets in Winchester Cathedral. Next week, one of the results – the skeleton of Queen Emma – will be revealed.

Winchester Cathedral has long been famous for its bone-caskets standing high up on the decorative screen surrounding the presbytery of Winchester Cathedral. Allegedly holding the remains of eight kings, one queen, and several bishops, the caskets were used to collect the royal bones, when their graves were desecrated during the Civil war in the 17th century. However, at that time the burials were already said to be in a sorry state, as “kings were mixed with bishops and bishops with king” when the individuals were reburied after the demolition of the Old Minster. Mangled and co-mingled since this first reburial in 1158, the bones were not representing complete skeletons.

Since 2012, a team of dedicated scientists has been busy trying to put the mess into some order, however, as part of an on-going research project supported by the Dean and Chapter of Winchester Cathedral.

In 2015, C-14 (radiocarbon) dating revealed that the bones were from the same periods as the names on the chests, confirming that the remains likely represented the alleged historical persons and not the result of later activity within the Cathedral. Following this, the scientists began to determine the number of individuals represented in the bone assemblages, along with their sex, age at death and physical characteristics. Studies have also been carried out on dental formation.

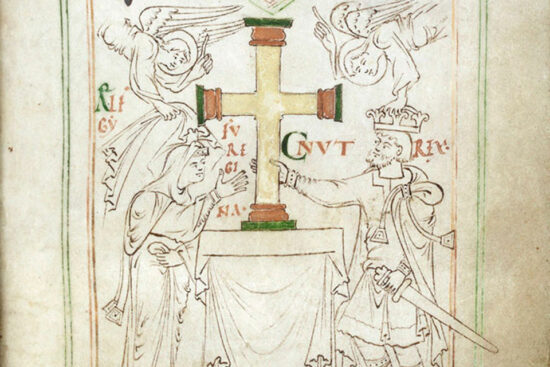

During this phase, the 1300 bones have been meticulously measured and recorded, revealing that the caskets contained at least 23 individuals. These skeletons were reassembled based on bone appearance and the estimated size and age of the individuals. One of the more exciting finds was the collected remains of a middle-aged or mature female, whose bones had been dispersed within several bone caskets. It is not yet certain, but these bodily remains could be those of Queen Emma, daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy, the wife of two successive Kings of England, Ethelred and Cnut, and the mother of King Edward the Confessor and King Harthacnut. She was an influential political figure in late Saxon England, and her family ties provided William the Conqueror with a measure of justification for his claim to the English throne. “We cannot be certain of the identity of each individual yet, but we are certain that this is a very special assemblage of bones” commented Professor Kate Robson Brown, who is leading the investigation. The bones of the female skeleton have been 3D printed and laid out as a key exhibit in the upcoming exhibition, Kings and Scribes: the Birth of a Nation., which opens on the 21stof May in Winchester.

Forthcoming research will seek to identify further individuals as well as characterize where they grew up, their diet and general health. In a Danish context, particular interest focus on the identification of King Cnut, whose nephew was found buried in a pillar grave in Roskilde. Thus, perhaps offering the possibility through analysis of aDNA of linking the individual found in a chamber-grave in Jelling (King Gorm?) with those of his great-grandson in Winchester and his great-great-grandson in Roskilde.

SOURCE:

Winchester Cathedral’s mortuary chests unlocked

Press Release, May 2019

READ MORE:

READ ALSO:

By Pauline Stafford

Wiley-Blackwell 2001