The history of Early Medieval Scotland is no longer just a history of the distinctive tribes: Celts, Picts, Vikings or Anglo-Normans

In the 19th century it became fashionable to measure the skulls of innocent people to find a scientific base for the idea that race really mattered. In Scotland these racial theories played out amongst medieval historians in terms of ‘Celtics’ against ‘Anglo-Normans’ (or Anglo-Saxons/Germans’). More specifically the question raged whether “Scotsmen were of a race, which produced poets, historians and philosophers… or they were of that race, which for centuries had not been able to preserve an independent existence” [1]

About ten years ago Matthew H. Hammond wrote a seminal article in The Scottish Historical Review, which elegantly summed up the historiography of this ethnic and racial filter, which for a century or more had influenced Scottish history at all levels. In this he described how historians for a long time had “tended to define medieval Scottish society in terms of interactions between ethnic groups. This approach was developed over the course of the long nineteenth century, a formative period for the study of medieval Scotland. At that time, many scholars based their analysis upon scientific principles, long since debunked, which held that medieval ‘peoples’ could only be understood in terms of ‘full ethnic packages’. This approach was combined with a positivist historical narrative that defined Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Normans as the harbingers of advances of Civilisation”. [2]

The prejudices of that era may have faded today, although modern Scottish History still relies all too often on this dualistic ethnic framework.

However, recent studies of Early Medieval Scotland from an archaeological perspective have shown how it makes sense to revisit the period up to the 11th century in a much more nuanced and reflective way, drawing upon cultural and historical anthropological research. This is a story, which is as yet not fully told amongst historians although some articles in a recent publication on New Perspectives on Medieval Scotland do touch upon the matter.

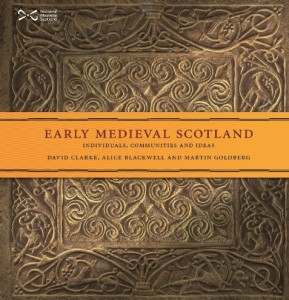

The main inspiration, however, is to be found in a very recent publication on Early Medieval Scotland published by the National Museum of Scotland as part of the Glenmorangie Research Project.

This project began in 2008. It took its inspiration from the stunning Hilton of Cadboll stone on display in the National Museum of Scotland’s Early People gallery. This stone was found near the Glenmorangie distillery in Tain, Easter Ross and was later incorporated into the company’s brand logo. As a follow-up the Whisky Company has been supporting a large research project aiming at understanding life in Early Medieval Scotland and its material culture from the bottom up – that is through careful analysis of the many precious objects left in the care of the National Museum of Scotland.

The book presents an overview of not only this and many other precious objects, but also the new insights, which have been reached through careful art-historical and archaeological analysis by curators, historians and archaeologists involved in this project. Sometimes, even, understanding has been achieved through working with modern craftsmen and artists charged with reproducing the splendor of some of these treasures. One example, of what these procedures have yielded, may be gleaned from a detailed presentation of the Monymusk reliquary.

What is especially interesting here is though that these iconic objects have been made to reveal a vast amount of new insights into the actual workings of the life and times of people living up until the 10th century in what later became Scotland. Thus it presents a remarkable sounding board for reading the scholarly books on Scottish History from the 11th century and onwards, which continue to be published, primarily in the series: The New History of Scotland as well as the New Edinburgh History of Scotland, both published by The University Press of Edinburgh.

It is to be hoped that this important work will inspire future historians in rethinking the Cultural History of Scotland

Wish to read more about Scotland the Brand and its medieval icons? Please follow the links below

Names, Sprigs, Feathers, Tartans and Kilts

NOTES:

[1] Duncan Keith, A History of Scotland. 1886 Vol. 1, pp. 35 – 36, as quoted by Hammond, Ethnicity p. 4

[2] Abstract, Hammond, Ethnicity p. 1

SOURCE:

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History.

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History.

By Hammond, M.H.

In: Scottish Historical Review, 2006, Vol. 85 (1). pp. 1-27.

ISSN 0036-9241

Early Medieval Scotland. Individuals, Communities and Ideas.

By David Clarke, Alice Blackwell and Martin Goldberg

National Museum of Scotland 2013