Nimes was briefly under Muslim rule in the early 8th century. Now the presence has been proven by the find of three Muslim burials

Early Medieval Muslim Graves in France: First Archaeological, Anthropological and Palaeogenomic Evidence

By Yves Gleize, Fanny Mendisco, Marie-Hélène Pemonge, Christophe Hubert, Alexis Groppi, Bertrand Houix, Marie-France Deguilloux, and Jean-Yves Breuil

In Plos One: February 24, 2016 as Open Access

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148583

ABSTRACT:

The rapid expansion of the Arab Empire during the Muslim conquests resulted in the formation of one of the most important empires in world history, extending from the west bank of the river Indus to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. The Arab-Muslim expansion represented a major politico-religious change during the early Middle Ages in the Mediterranean region. In the western part of the Mediterranean, Arab armies expanded quickly across North Africa and incorporated numerous native Berbers populations, which rapidly adopted the Islamic religion and represented the bulk of Muslim troops who later conquered Southwest Europe. The Umayyad army invaded the Iberian Peninsula via North Africa in 711 AD and rapidly conquered the Visigothic kingdom, which, from the 5th to the 8th centuries AD, and spread across what are now southwestern France from AD 719. Their arrival led to a cultural transformation and substantially modified relations between Western European societies that were being reorganized after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Textual sources, specifically the Moissac and Uzès chronicles, offer a significant testimony to the complex and unstable historical context of the Nimes region during the early Middle Ages. They notably attest to a Muslim presence or travel in Nimes between 719 and 752 AD. The city—at that time called Niwmshû or Namûshû by Muslim authors—would have initially been taken by the “Saracens,” possibly at the end of 719, but was rapidly retaken by Eudes, Duke of Aquitaine, in 721. In 724 or 725, the inhabitants of Nimes surrendered, offering little resistance to Ambissa, or Anbasa b. Suhaym al-Kalbi, the new governor of Spain. Despite the city’s devastation by Charles Martel in 737, Nimes’ Muslim presence may have persisted after this date. Finally, in 752, a local Goth leader named Ansemundus (or Misemundus) delivered four cities, including Nimes, to Pepin the Short, marking the start of the final conquest of Septimania by the Franks.

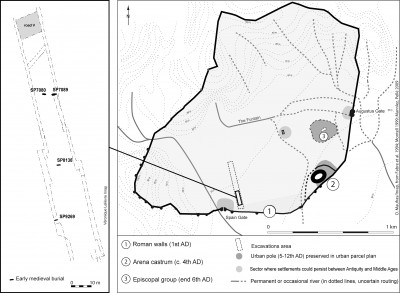

In accodance with this, the Islamic presence in Septimania has until recently only been archeologically documented by rare ceramics, Arabic coins or seals. The discovery in 2006 of three Muslim burials in Nimes (Languedoc-Roussillon, France) immediately appeared as a unique opportunity to document the “Saracen” settlement in the South of France.

A multidisciplinary study was then developed combining

- archaeological analyses to characterize the site funerary practices, to determine the burials dating, and to discuss the burials’ integration in the Nimes funerary context

- anthropological analyses to test the potential attribution of the individuals to Arab army soldiers (through sex and age individuals’ characterization, and through the search of potential osteological evidence of combat)

- palaeogenomic analyses to provide biological arguments concerning individuals’ origins.

The multidisciplinary analyses conducted on these burials offer new data concerning the Muslim occupation in the Visigothic territory of Septimania, unraveling the complex relationship between early medieval western and Arab-Muslim societies.

Interestingly, several observations suggest that the three Muslim graves were not isolated or excluded from general funerary space. First, although the three Muslim graves were discovered in an area surrounding the city (outside the borders of the early medieval town), they were found in a distinct rural area situated inside a Roman enclosure (demarcated by stone walls) and between urban poles. Because the Roman walls were still partially visible in the early Middle Ages, we can speculate that this funerary zone was in some way still linked to the city. Moreover, the Muslim graves were not isolated in the area because other early medieval graves were found in the suburb of Nimes, corresponding to a well-known phenomenon in the early Middle Ages. This testifies to a casual mingling of Muslim and Christian graves and – perhaps – witness to a complexity of relationships “between communities during this period, which cannot be summarized in a simple opposition between Christians and Muslims”, concludes the authors.

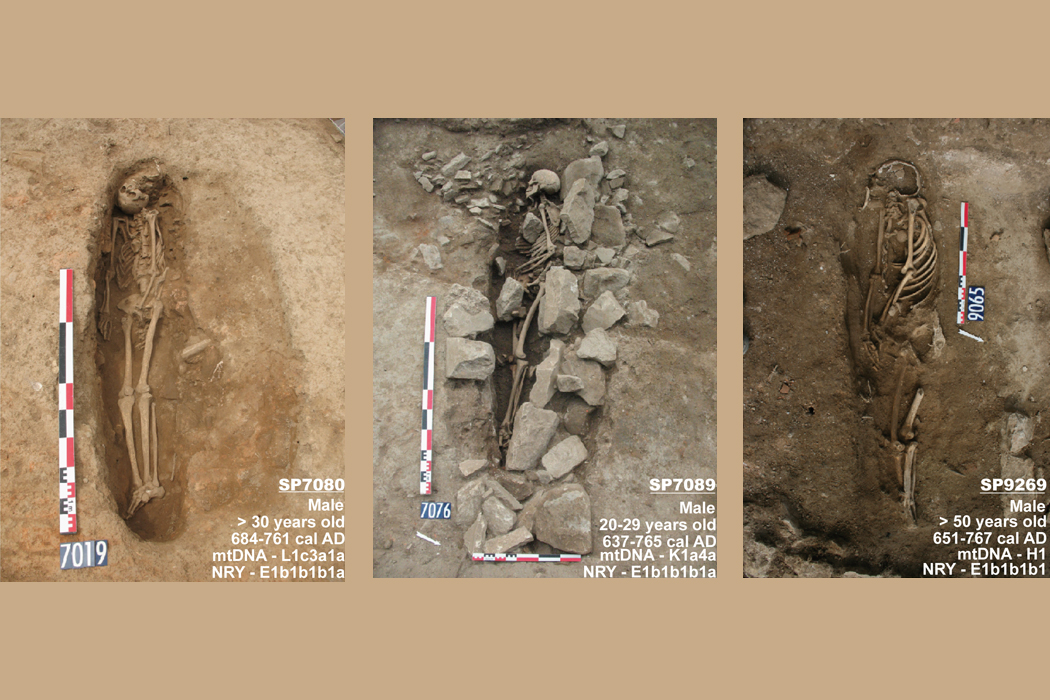

Five human bone fragments from the three graves underwent direct radiocarbon dating (S2 Table). The dates obtained, confirmed by two dating labs, cluster tightly and range between the 7th and the 8th centuries AD. These dates suggest that the remains are the earliest medieval Muslim graves known in France. An anthropological analysis shows that the three skeletons are those of male adults. Although it is difficult to be certain of the biological identity of these individuals, several anthropological characteristics can be highlighted. The skeletons did not show any marks indicating death resulting from fighting. The skeleton from SP7080 displayed an incomplete fusion between the right pisiform bone and the hamate bone (S2 Fig). This extremely rare fusion, mainly seen in African populations, suggests an African origin for the Nimes human remains. Nevertheless, no dental decoration, potentially testifying a North African origin and already described on a skeleton discovered in the site of Plaza del Castillo in Pamplona, could be observed on the Nimes individuals. Paleogenetic and palaeogenomic analyses were conducted on the three Nimes individuals to better understand their bio-geographical origin.

Given the multidisciplinary nature of this study, which combines archeological, anthropological, historical and palaeogenomic discussions, the three Muslim graves from the site of Nimes are attributed to individuals with paternal ancestry from the Maghreb. These burials, dated between the 7th and the 8th century AD, represent the earliest medieval Muslim graves known in France. This discovery has had a resonance, especially in available textual sources that indicate a few decades of Muslim presence in Nimes, between 720 and 752 AD. We suggest that the graves discussed in this study can provide further insight into the nature of this Muslim presence. Indeed, the discovery of funerary rites faithful to Muslim customs offers evidence indicating the presence of a community that was familiar with and practiced Muslim customs in Nimes during this period.

Despite the low number of Muslim graves discovered, the authors “believe that these observations provide strong evidence for either the establishment of a garrison or a more long-term establishment of Muslim communities in Nimes. Moreover, the results we discuss demonstrate that a few years after their integration into the Muslim world, North African populations were interred according to Islamic customs. This observation lends strong support to the quick conversion of the Berber populations and testifies to the velocity of the politico-religious changes involved in the Arab Conquest.” However, the

SOURCE:

Read the full article here

FEATURED PHOTO:

In situ photographs of the Nimes burials, with a synthesis of age and sex of individuals, radiocarbon dates, maternal and paternal lineages. Note that the number near the funerary pit is the recording number of the picture. The stones around the burial SP7089 correspond to a roman wall and some stones were reused to close the funerary pit