New research sees the Chronicle of Dudo’s as primarily a didactic text meant to teach courtly values to a new cadre of elite managers at the court of the Norman Dukes in the beginning of the 11th century

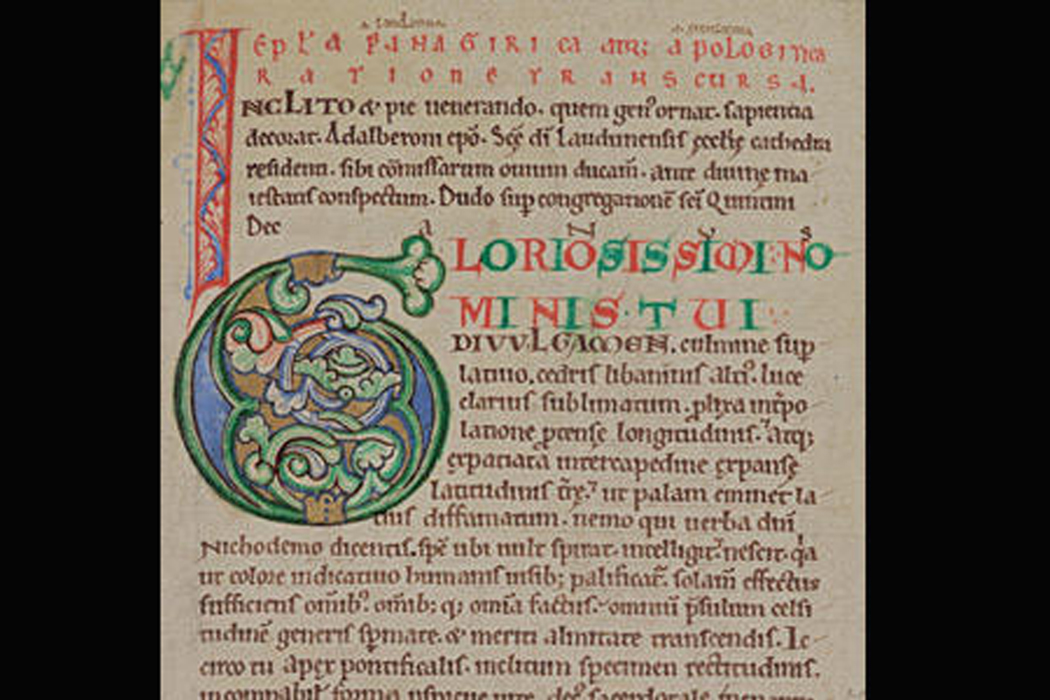

Dudo of St. Quentin (965 – ?) wrote a(n in)famous chronicle about the deeds of the Normans, the Gesta Normannorum. Usually disparaged as a reliable source for anything at all except the eccentricities of the author, new research presents a plausible explanation of its audience and form; thus making it more accessible to scholars working with the early and later history of the duchy of Normandy.

According to Dudo himself, Duke Richard I shortly before the death in 996 urged him to write the history of the Normands. After his death the son and uncle continued to support his work. It is however, generally believed not to have been finished until 1015 after Dudo returned to his original house of Saint-Quentin to serve as dean. Famously presenting a very eclectic and curious story, Dudo’s work has traditionally been consigned to the scrap-heap of literary fiction.

If historians, nevertheless, have tried to tackle the enigmatic text, they have often ended up parading widely opposing conclusions. Here discussion has focused on what the dukes might get out of sponsoring a work as enigmatic as Dudo’s. On one hand David Bates believe that Dudo was “concerned to belittle the memory of the Scandinavian past” [1], on the other hand Emily Albu has argued that although Dudo considered the Normans as fully integrated into the Christian culture, his aim was also to demonstrate a certain covert message of “wolf-like ferocity” which might be activated in times of trial [2]. Others have seen the work as homage to the Christian ideals of the dukes (some have even seen it as a piece of writing essentially hagiographical in its character.)

In a recently published article, Michael Gelting, writes that “none of these interpretations are necessarily mutually exclusive”. However, by way of a very careful consideration of the text as such, as well as a close reading of specific central passages, he succeeds to at least propose a very probable general context for the chronicle.

In short Michael Gelting argues that the writings of Dudo were meant as a didactical tool to be used in the teachings in the leading Cathedral School in Rouen in the beginning of the 11th century, bringing it up to “international” standards. The goal was to create a local group of intellectuals from which it might be possible to recruit a well-educated governing class. Such schools had as their objective to teach Latin, the seven liberal arts plus piety. But they also aimed at providing the students with a moral – courtly – upbringing. As Gelting writes, turning them into dignified, self-conscious, morally upright, public-minded, wise, eloquent and moderate persons; all virtues exalted in the stories about the Dukes of Normandy and their progressive deeds (p. 19).

In the article Michael Gelting stresses, that he is not going “to address the general veracity of the writings of Dudo”, but he does use his new-won understanding of the text to see how it explains the educational principles outlined in the histories of the dukes. Through this he shows, how a distinct pattern of progression can be traced from the barbarian wildness of Rollo and his Vikings, being tempered by Christian Piety in William Longsword and finally fusing “into a harmonious whole” by the proper education in Richard I (p.29). The looming – but, alas probably unanswerable – question is, whether the chronicle was written as a didactic tool to be used in the upbringing of the many children in the ducal household in the beginning of the 11th century. Was Dudo perhaps the headmaster?

In the conclusion Michael Gelting very carefully stresses that his interpretation of Dudo’s chronicle as an exponent of the courtly ideals of the late 10th and early 11th century “does not in any way pretend to be exhaustive”.

However, it seems fair, to state that anyone, who in the future intends to mine Dudo’s vivacious stories and fascinating poems, should reconsider why any specific meme was included by Dudo and what role it was meant to play in his didactic programme.

SOURCE:

The Courtly Viking. Education and mores in Dudo of St. Quentin’s Chronicle

By Michael H. Gelting.

In: Toogtredivte tværfaglige vikingesymposium. Syddansk Universitet 2013. Pp. 7 – 36. Ed by Lars Bisgaard, Mette Bruus and Peder Gammeltoft. Forlaget Wormianum 2014.

Michael H. Gelting is professor in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Aberdeen.

Karen Schousboe

READ MORE:

The principal editions of Dudo of St. Quentin are

De moribus et actis primorum Normanniæ ducum auctore Dudone Sancti Quintini decani.

Ed. by Jules Lair.

Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de Normandie 23.

Caen, 1865

Dudo of St Quentin. History of the Normans.

Tr. by Eric Christiansen.

Woodbridge, 1998.

ISBN 0-85115-552-9.

Viking Normandy: Dudo of St. Quentin’s Gesta Normannorum.

Tr. by F. Lifshitz.

Internet publication 1996 – www.the-orb.net

____

[1] Normandy before 1066. By David Bates, London 1982, p. XVI – as quoted by Gelting.

[2] The Normans in their histories, Propaganda, Myth and Subversion. by Emily Albu, Boydell & Brewer 2001, pp. 41 -6 – – as quoted by Gelting.