Cnut the Great is one of the overlooked English kings. Maligned as aprimitive Viking conqueror, the story has most often been told as a civilising project carried out by Emma. Not so in this new biography.

Cnut the Great

By Timothy Bolton

Series: The English Monarchs Series

Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2017

REVIEW:

This biography has been in the crucible for a long period beginning with the work leading up to the thesis of Timothy Bolton at Cambridge from 2005 on the Empire of Cnut the Great. At a price of €154, this has been out of reach for most people without academic library access, and it is obvious that Yale contracted Timothy Bolton to deliver a more accessible version of his work to the wider English-reading public. Published in The English Monarchs Series and for sale at a generous price of $25 – 40 the story about one of the most overlooked English kings is bound to reach far – lǫndum ǫllum, as the Skald, Óttarr svarti promised in his Lausavísa (Poem of Praise).

As this is a biography, we are, of course, treated to a detailed outline of his life. Cnut (Knud den Store) was born sometime in the end of the 10th century in Denmark as the son of Sven “Forkbeard”, (Svend Tveskæg) and grandson of Harold Bluetooth (Harald Gormsen), known as the King of Jelling. His mother was a Polish princess, sister to the king of Poland, Bolesław I, the Great (Bolesław I Wielki). During the reign of Æthelred his father was involved in numerous raids on England in 1003 – 5, 1006 – 7 and again in 1009 – 12. Finally in 2013, Sven Forkbeard succeeded in conquering England. Unluckily, on his way to be crowned king at York, he died, and Cnut was left to deal with the situation. At first he had to withdraw. In 1015, however, he returned to England as head of his own army. During the following year he succeeded in gaining control of the war-weary country, and at Christmas, he was crowned king of England in London and recognised in January in Oxford by the English nobility. The next years were filled with energetic work; on one hand, Cnut had to secure the support of the English elite; on the other hand he had to feed the “beast”, his Viking crew of Scandinavian elite warriors, his Hauscarls, and the men of his supporters. Probably, one act of genius was to secure the hand of Emma of Normandy, the former wife of Æthelred and sister of his ally, the Duke of Normandy. Through this marriage, he was able to safeguard his “back” to the south as well as get access to her alliances with the English church. It is during these first two years, his vast law-codes were promulgated, one ecclesiastical and another secular.

Nevertheless, when his brother, the king of Denmark, died in 1019, Cnut went back and succeeded in installing one of his sons as his representative, thus gaining an important foothold in what was later to become the other significant part of his north-western empire. The next seven years saw Cnut going back and forth between his two kingdoms quelling rebels, rewarding friends and in general establishing a firm base for his double kingship.

Occasionally, historians are puzzled about how this was achieved. However, we know from the writings of Adam of Bremen (and archaeological experiments) that if the weather is generous, it takes no more than three days to sail back and forth between England and Denmark. As Limfjorden, a large firth in the north of Jutland was still open to both the North Sea and the Skagerak at this time. Through this it was easy to reach the new royal centres located around Øresund. Often forgotten, forests and mountains divide, while water unites.

We cannot know exactly to what extent Cnut or his (more or less) loyal retinue went back and forth. It is highly likely, though, that it was much more often than not. Rulers in the 11th century were itinerant. They had to be seen, to be acknowledged; and they had to be seen continuously recirculating gifts – valuables, exotic textiles, weapons, horses, land, and probably also ships. It is during these years, Timothy Bolton writes, we get glimpses of a Christian king involved in forging the disparate parts of his empire into a smooth-running, tax-paying unity. Although his grandfather, Harold Bluetooth may have experimented with building a monetary system, the coins of his father, Sven Forkbeard, were the first to carry the portrait of the king and to be fitted with an identifying inscription. These were minted in Lund in Scania c. 995 by an Englishman, Godwine. From c. 1020 Cnut the Great, commenced minting on a much larger scale. Coins were minted not only in Lund but also in Roskilde, Ringsted, Viborg and Ribe. At first, these coins were of a bewildering quality witnessing to a situation in which minting coins seems to have been a free for all. Around 1030, though, this seemed to change. Now systematic minting took place at Lund, Roskilde, Slagelse, Ålborg, Viborg, Ørbæk, Århus, Ribe and Haithabu.

Timothy Bolton is of the opinion that the main impetus and inspiration for these state-building activities in Denmark came from England. And yes, it is correct that his coins were minted by moneyers with Anglo-Scandinavian names. However, the later coins used motives from a wider European context. At the same time they were sometimes fitted with a coiled serpent – probably the Jörmungandr – seemingly a “national” element used at Haithabu from the 9th century and perhaps adopted in Cnut’s later reign as a “peacekeeping” symbol in a world with significant pagan roots. Perhaps also the “worm” was a totem of the family as witnessed by the recurrent use of the family name of Gorm, which disappeared after Christianisation was fully adopted. Even if there is no doubt, Cnut was a card-carrying member of the Christian world, and chroniclers liked to present him as a pious man, we have to note the fluidity of the cultural worlds, among which Cnut moved with dexterity.

Another characteristic element, though, was the substantial inspiration, which Cnut obviously gained from his close contacts with the Holy Roman Emperor, Conrad II. After having seized control over Norway and Western Sweden in 1026, Cnut was so secure in his saddle that he could travel to Rome to witness the coronation of Conrad II at Easter and further his diplomatic contacts with this mighty neighbouring ruler down south of the border of Denmark. Timothy Bolton floats the idea that Cnut was involved in a game of high politics, “secretly” supporting the Duke of Aquitaine in his aspiration for the imperial crown. For this, though, the evidence seems too flimsy: The record of a gift of a precious manuscript written in golden letters to Aquitaine and the firm knowledge that the Duke was invited by the cities in Northern Italy to explore his opportunities, does not have to be linked. It is perhaps more likely that the gift was intended to secure a free passage for traders and ships along the western French coast, something which we do know had Cnut’s attention.

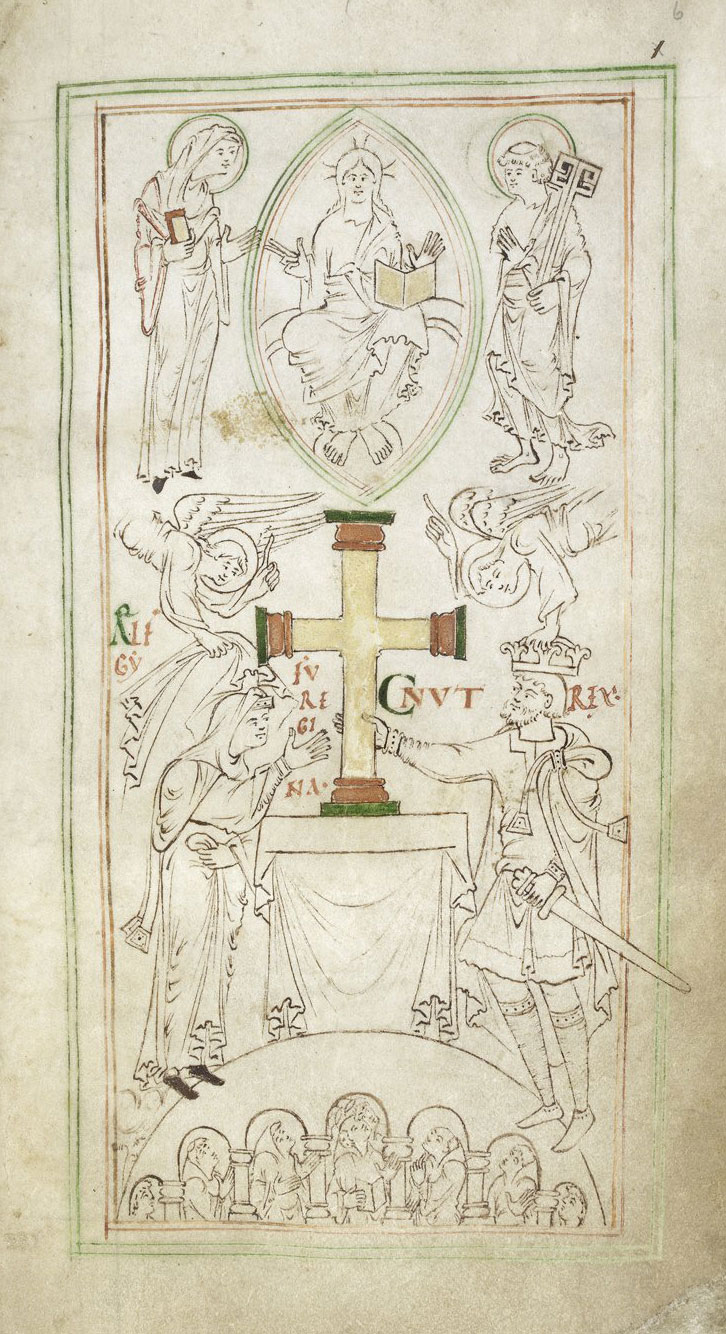

That Cnut was also inspired by the idea of “empire” is without doubt. As is well-known, the Holy Roman Emperor sported a special crown, which main part was designed in the 10th century. To this, however, Conrad II, added a special arch with the inscription “ROMANORU(M) IMPERATOR AUG(USTUS)”. It is likely that the idea of fitting the distinctive imperial crown with such an arch stems personally from Conrad and his close advisers and that inspiration came from the crests on Roman Imperial helmets. What is fascinating, of course, is that the crown of Cnut, which the angel places on his head in the illumination in the Liber Vitae from 1031, is fitted with an identical arch. Another indication of the inspiration of how to behave as an 11th-century king/emperor can be found in the description of how he wetted the floor of the pavement in the church of St. Omer with his tearful kisses. As Elaine Trehaine has argued, Cnut in this respect was endowed with the same Christ-like sacrosanct status as that which the new Salian dynasty in Germany was busy adopting in the first half of the 11th century. In the end, of course, this German orientation in Cnut’s political network was cemented when his daughter was married to the son and heir of Conrad, Henry III; at which point Cnut succeeded in pushing the border of Denmark south of the traditional, located at the river Eider.

Timothy Bolton uses such evidence to bolster his take on Cnut: that he was a smooth, international operator with a very powerful base – England and Scandinavia; and that this created opportunities for him to meddle in high politics at another level than would otherwise have been expected of a Viking warrior king from Scandinavia. However, the shoe might, in fact, also have been on the other foot. As it were, Conrad had huge interests in keeping Cnut happy, as his main sphere of interest was controlling the threats on his eastern borders reaching from Poland in the north to Hungary in the south. Conrad did campaign unsuccessfully against Poland in 1028 – 30 and probably needed to be sure that the Polish dukes/kings did not get help from their Scandinavian family and relations.

Why is it important to note such details in a review of this biography? The reason is, that while we get a detailed and thoughtful account of how Cnut built his powerbase on his network of both English and Scandinavian allies – and their diverse cultural traditions – we a left with less insight into the continental inspiration. It is this general European setting, which is slightly disregarded in this biography. Instead, we are treated to a very impressive recount of the socio-political landscape of friends and foes as can be gained from the English prosopography. One obvious challenge is that Timothy Bolton seems to be less fluent in German than the Scandinavian languages. Obviously, there is much German research focusing on the contemporary Ottonian and Salian rulers, and there is ample opportunities for to supplement the presentation of the lifeworld and worldview of Cnut with what a closer scrutiny of what went on further south.

When all is said and done, Timothy Bolton, nevertheless, writes a fine story. First, the reader is introduced to the historiography, which outlines the skewed focus on the English sources and narrative; and then we are introduced to the other side of the flipped coin: the Scandinavian world in which Cnut spent at least as much time and energy shoring up his realm. One challenge here is that we seemingly know less because there was no written bureaucracy. This was an oral society. The more precious is the evidence left in the Skaldic verses, which – because of their intricate structure and their use of kennings (circumlocutions) are considered preserved unchanged in later sagas and chronicles. The point is that numerous Skalds worked the “mead-halls” of this Scandinavian king, and has left us invaluable witnesses not only to what happened but also what this might tell us about the life-world and personal habitus of this king.

Studies of these texts are deftly carried out and leave the reader with a deep sense of the fundamental incongruity of the cultures of these two worlds – the Anglo-Saxon and the Scandinavian; but it also serves to demonstrate how Cnut’s Northwestern Empire was slowly turning into a cultural amalgamation. How this process played out in the end, though, the reader must, unfortunately, turn elsewhere to be enlightened about. The reason is that the extensive archaeological research, which has been carried out in the last ten to fifteen years seems to have been partly set aside by Timothy Bolton.

To conclude: It is evident that Timothy Bolton masters the English written sources of the period. We get a finely tuned history of the means and ways in which Cnut wielded power through the machinery of government, carried out by the personnel in the English church. It is also apparent that Bolton has a somewhat fine ear for the complexities of utilising the few, limited and late written sources from Scandinavia. But it is also obvious that the strength of Bolton’s approach is the significance he attaches to political history. This is not a historical-anthropological history of the life-worlds and worldviews of Cnut. And yet, on the other hand, it is an valuable introduction for cultural historians and archaeologists to what a political historian fostered in the English tradition can wring out of his source material, which they too often tend to consider enigmatic and unapproachable. However, we still need a cultural-historical biography written in the grand tradition of the annales historians…

Karen Schousboe

READ MORE:

The Empire of Cnut the Great. Conquest and Consolidation of Power in Northern Europe in the Early Eleventh Century.

By Timothy Bolton.

Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers 2009.

ISBN 9789004166707

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Timothy Bolton is the author of The Empire of Cnut the Great: Conquest and the Consolidation of Power in Northern Europe in the Early Eleventh Century. He is an honorary fellow of both Cardiff and Aberdeen Universities, and lives in Stockholm, Sweden. He is also Head of Western Manuscripts and Miniatures at Bloomsbury Auctions.

READ ALSO: