Cleveland Museum of Art celebrates its centenary with several events. For medievalist an exhibition of Cleveland’s Gothic Table Fountain is exciting

Myth and Mystique: Cleveland’s Gothic Table Fountain

Cleveland Museum of Art, Julia and Larry Pollock Focus Gallery | Gallery 011

Centennial Exhibition

09.10.2016 – 26.02.2017

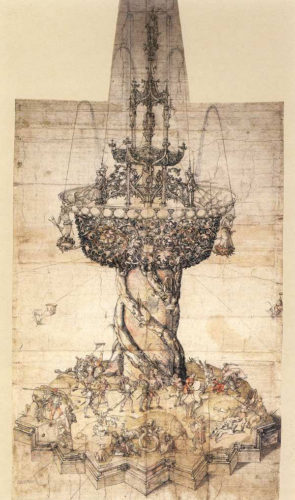

The most complete surviving example of a Gothic table fountain is preserved in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Dated to the period between 1320 – 40 is made of gilt silver and fitted with panels in translucent enamels, made in the basse-taille technique. It measures no more than 31 x 24 x 26 cm and is likely to have been fitted with a now lost basin. Water would have been hydraulically pushed up through a pipe in the base and then allowed to fall down into the basin – on the way cascading merrily, while making bells tinkling and wheels turning. Possibly it would have been placed on a hollow pillar with the pipe connecting with either a higher placed reservoir or a pumping-system located apart. This might then be worked by a servant letting the sweet rose-water sprinkle in the fountain to the delight of people standing by.

Conceptually and stylistically, the Cleveland table fountain is stunning piece of Gothic architecture in miniature, with parapets, arcades, vaults, pinnacles, columns, and arches with tracery. The goldsmith responsible for this object was unquestionably inspired by the great Gothic buildings of his time. The Cleveland table fountain is a three-tiered assembly featuring cast and chased elements to which were attached a series of enamel plaques representing grotesque figures, some of which play musical instruments. Water wheels and bells were added to capture motion and sound. The rich detail and ornamentation of this object suggest it would have been expensive to produce and highly treasured by its original owner.

It is well-known that nicely cut water-basins were fitted into the walls of the lord’s chambers in 12th and 13th century castles. Placed near the walls and next to entrances, they offered people a chance of tidying up before commencing work of all sorts. In more mediocre circles like burgher’s houses stationary lavers continued to be a common feature in the late middle ages. 14th century fountains may at first have been a more conceited way of expanding on this idea, to have fresh water near at hand.

Soon, water fountains like the one from Cleveland and other such automatons were highly sought after by the elite in the 14th century. For instance, the French king, Charles V had two fountains listed in an inventory in 1380. Louis I d’Anjou listed in his tresór 38 table fountains, of which some were larger than that from Cleveland while others were of the same size (as compared according to weight). Based on a recent reexamination of the fountain one of the curators have argued the case that the fountain at some point was gifted to a royal chivalric society founded by John the Good in the mid 14th century.

Formerly such fountains were thought to have graced the tables at great feasts. However, detailed studies of illuminations of such events have failed to uncover any pictorial witnesses to this practice, and it is now generally believed they belonged to the category of wondrous amusements designed to thrill with their “automatic” qualities. Impressive in their sheer technical wizardry, these mechanical devices with moving parts that spouted (sometimes perfumed) water are known especially from royal or noble inventories and testaments. Such objects did not originate in the European West, but were probably introduced through the Byzantine and Islamic worlds.

These fountains were more than anything forerunners of the expensive toys, which are known from later princely collections from the Renaissance. They assumed various forms but were always made from precious metals and sometimes embellished with colorful enamels or semi-precious stones. Table fountains were probably returned to the goldsmith’s shop for conversion into vessels or coinage once they ceased to function or the fashion had passed, accounting for the scarcity of surviving examples today.

Cleveland Museum of Art

The Gothic table fountain in the Cleveland Museum of Art is unique. Apart from some preserved fragments, this is the only one that has come down to us. Its provenience before it ended up in Cleveland in 1924 is basically unknown. Some cloak and dagger story tells it was found dug down in a garden in Constantinople during WWI, but the fact remains that no one really knows.

This exhibition does, for the first time, present this unique and special object as the focus of a single study. The table fountain is placed at the centre of a group of objects including luxury silver, hand-washing vessels, enamels, illuminated manuscripts and a painting by Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and the Child at the Fountain. Each informs some aspect of the fountain’s history, functionality, presumed use and context, materials, technique, dating and style.

The exhibition includes important loans from international lenders and is co-curated by Stephen N. Fliegel, curator of Medieval art, and Elina Gertsman, professor of art history at Case Western Reserve University.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is generously funded by Cuyahoga County residents through Cuyahoga Arts and Culture. The Ohio Arts Council helped fund this exhibition with state tax dollars to encourage economic growth, educational excellence, and cultural enrichment for all Ohioans.

SOURCE:

Cleveland Museum of Art solves mysteries of its medieval French table fountain

Catalogue:

Myth and Mystique: Cleveland’s Gothic Table Fountain

By Stephen N. Fliegel and Elina Gertsman

Published by GILES in association with the Cleveland Museum of Art 2016

READ MORE:

The Cleveland Table Fountain and Gothic Automata

By Stephen N. Fliegel

In: Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, (2002) Vol. 7, pp. 6-49

A Glimpse at the Fountains of the Middle Ages

By William D. Wixom

In: Cleveland Studies in the History of Art (2003), Vol. 8, pp. 6 – 23

Aristocratic Power and the “Natural” Landscape: The Garden Park at Hesdin, ca. 1291–1302

By Sharon Farmer

In: Speculum (July 2013), 88, no. 3, pp. 644-680.D

Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art

By E. R. Truitt

University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015