In the period known as the Dark Ages (c. 300 - 700 AD), woodlands staged a remarkable comeback across Europe, including the Netherlands.

In the period known as the Dark Ages (c. 300 - 700 AD), woodlands staged a remarkable comeback across Europe, including the Netherlands.

In AD 763 volcanic eruptions in Iceland caused Icebergs in the Black Sea and a nearly frozen Bosphorus causing widespread fear

For some historians (Reynolds 1984), feudalism is a concept created in the 17th century and used in the 19th century to describe the world before the more enlightened times of modernity. For others, it has acted primarily as a conceptual opening to explore the endless complexities of economic and social ties in the Middle Ages in the Maconnais, in Bourgogne or elsewhere.

Archaeology, however, has, during the last fifty years, uncovered a series of clear breaks in the European landscapes in the 10th and 11th centuries, demarcating feudalism as a distinct new socio-economic way of living and thinking about the world. These findings correspond to the history written by several French historians from the Annales School, who took pains to explore these new ways of thinking about land, tributes and taxes and the corresponding system of obligations welded into the fabric of medieval society in the High Middle Ages. (c. 1000 – 1300)

This new and transformational way of thinking originated in a world devoid of towns, money and markets. Instead, the cultural habits were based on economies of gifts, barters, and trading ventures. Here, a tribal outlook governed the social and economic relations among people wherever the iron grip of the Carolingian world order did not reach. Which was, in fact, not pervasive throughout Europe in the 8th and 9th centuries.

In the post-Carolingian world, budding feudalism organised a world gradually marked by private fortified homesteads, villages, and an economic upsurge in material wealth for the wider society. This materialism took off in the 9th century and flourished in the 10th century and later. Arguably, this shift was part of the interplay between centres and peripheries, leading to (among other alterations) the swinging seesaw between Carolingian France and Ottonian Germany.

More precisely, feudalism is generally understood as a reflection of the

As such, feudalism and feudal domination constituted a mode of production based on a specific organisation of exploitation of landed wealth and supported by the theology and religious thinking of the times. In time, it fostered a distinct lifestyle, the epiphenomena of the Middle Ages’ social and material culture and outlook.

Central to the outlining of the concept of feudalism were the works of French historians such as Marc Bloch (1886-1944), François-Louis Ganshof (1895-1980), Georges Duby (1919-96) and Jaques le Goff (1924-2014).

The latter two were primarily inspired by Marc Bloch and his definition based on the following characteristics: a peasantry consisting of tenants, a distinct warrior class, a cultural thinking based on violence, protection and obedience called vassalage, a fragmentation of state-sponsored rule and monopolised violence framed by dynastic thinking about familial and associative thinking.

“European feudalism should, therefore, be seen as the outcome of the violent dissolution of older societies. It would, in fact, be unintelligible without the great upheaval of the Germanic invasions, which, by forcibly uniting two societies originally at very different stages of development, disrupted both of them and brought to the surface a great many modes of thought and social practices of an extremely primitive character. It finally developed in the atmosphere of the last barbarian raids. It involved a far-reaching restriction of social intercourse, a sluggish circulation of money to admit salaried officialdom and a mentality attached to tangible and local circumstances. When these conditions began to change, feudalism began to wane.” (Bloch 2004, p 443).

Based on this understanding, Bloch developed his ideas of the two “feudal ages”, of which the First Feudal Age reached from the collapse of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century to the mid-11th century, while the second feudal age covered the period from the mid 12th century to the mid 14th century and into the waning of the Middle Ages. Unlike this definition, Ganshof focused on the feudo-vasallic relations where feudalism was considered a system ruling duties concerning aid, obligations, and service (Ganshof 1961).

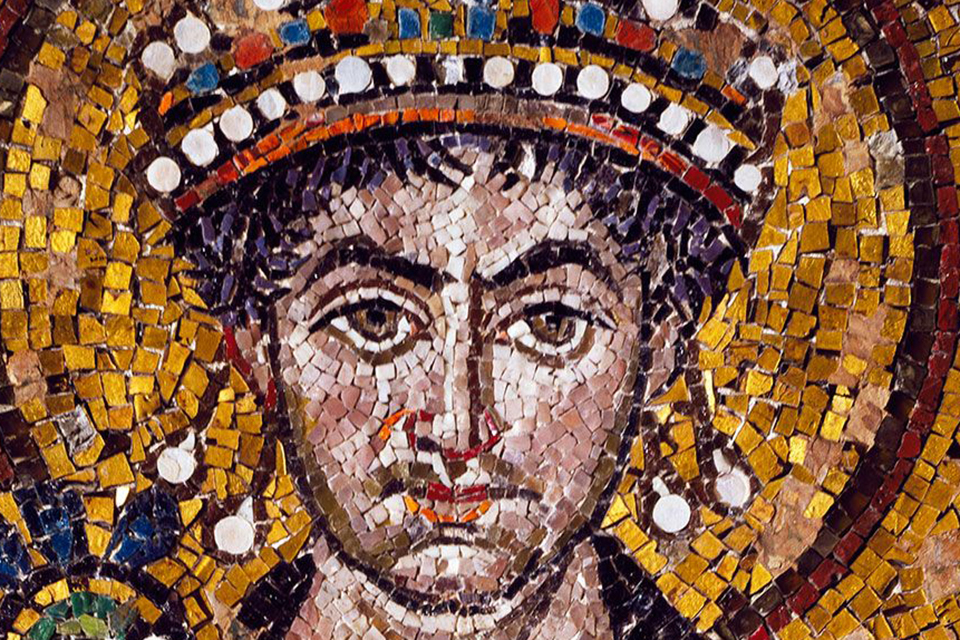

The cusp of the feudal age must be found in the economic and cultural decline, notably marking out the period from c. 500 – 700, with different timespans evoked in different parts of Europe. During this period, the Byzantine Empire virtually collapsed, leading to a decline in long-distance trade in the Mediterranean as well as in the North Sea and the Baltic.

During this period, the landscape and the towns became ruralised, if not abandoned. Europe closed off and fell into a disjunct and dispersed countryside where peoples’ lives were based on a subsistence economy pared with a gift economy. This was a period of economic decline and the formation of closed-off political and linguistic peripheries.

Interestingly enough, the first economic revival took off in the later Merovingian north, in the deltas of the Seine and Rhine with their tributaries, the Channel and the North Sea region reaching into the Baltic. Noticeably, this area came to foster a number of semi-religious central places surrounding lordly halls, to be followed by foundations of the emporia such as Quentovic, Dorestad, Ribe and later Haithabu, Birka, and Kaupang being linked up with York and London.

As opposed to this, the Mediterranean lacked behind, furthered by the Arab expansion in the 8th century and its culture of piracy and slave-raiding (the revisited Pirenne Thesis). Not until the late 9th and early 10th century did Italy and Iberia gradually revive through the short-term Carolingian and Ottonian efforts to revive the Roman Empire in a new disguise. These efforts, however, fell apart with the decentralisation of power establishing more or less independent kinglets and warlords as regional oppressors.

In the long run, Bloch’s work has stood better against the tides than Ganshof’s, claims the archaeologists (Hodges 2020). The last fifty years of archaeological surveys and excavations have furnished the evidence. Uncovering the decentralisation of the landscape dominated by the motte-and-bailey castles on hilltops, the amalgamation of grand estates, the corresponding nucleation of settlements in the form of villages and the continued reorganisation of the agrarian systems and the gradual expropriation of other natural resources such as forests, fishing waters, and hunting by kinglets and local warlords have documented this shift.

Gradually, all this led to a distinct upheaval in the economic and material culture of the elite, formalised in new lifestyles and ways of thinking based on the so-called “cerealisation” of the economy created through the dispersal of new systems of cultivation and technologies and the development of secondary products from the first half of the 9th century. The archaeological finds of grain silos, granaries, and traces of three-field systems and variations thereof have witnessed this process.

Today, the process of feudalisation, which was forged in the crucible of the dissolution of the Carolingian Empire, has been documented through textual evidence and archaeology of landscapes, settlements and, not least, the elite centres from 10th-century Europe, as well as through dedicated monographs on the history of specific regions and localities.

Defining the Archaeology of Bloch’s first Feudal Age. Implications of Vetricella Phases I and II for the making of Medieval Italy (8th to 9th centuries)

By Richard Hodges (2020)

In: The nEU-Med project. Vetricella, and Early Medieval royal property on Tuscany’s Mediterranean. Ed. By Giovanni Bianchi and Richard Hodges. Archaeologia Medievale (2020)28

How did the Feudal Economy Work? the Economic Logic of Medieval Societies

By Chris Wickham 2021

In: Past & Present , Volume 251, Issue 1, May 2021, Pages 3–40,

The Archaeology of the Peasantry in the Early Medieval Age. Reflections and Proposals.

By Helena Kirchner (2020)

In: Imago temporis medium aevum, XIV (2020) pp 61-102

Charismatic Kingship

By Weber, Max.

From: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Grundriss der verstehenden Soziologie. Mohr: Tübingen. 1922

Economy and Society. An Outline of Interpretive Sociology

By Max Weber. Engl. Translation ed bye Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. California University Press 1968, p. 1141-43.

“A particularly important case of the charismatic legitimation of institutions is political charisma, as it appears with the rise of kingship.

Everywhere the king is primarily a warlord. Kingship originates in charismatic heroism. In the history of civilized peoples, kingship is not the oldest form of political domination, that is, a power transcending patriarchal authority and differing from it because it does not primarily direct the peaceful struggle of man with nature but the violent struggle of one community against another.

Kingship is preceded by all those charismatic forms that assure relief in the face of extraordinary external or internal distress or promise success in risky undertakings. In early history, the precursor of the king, the chieftain, often has a double function: He is the patriarch of the family or siblings but also the charismatic leader in hunt and war, the magician, rainmaker, medicine man—hence priest and doctor, and finally, the judge.

Frequently each of these kinds of charisma has a particular bearer. Next to the peacetime chieftain (the head of the kin), whose power originates in the household and has mainly economic functions, stands the hunting and war leader, who proves his heroism in successful raids undertaken for the sake of victory and booty.

Even in historical times, in Assyrian royal inscriptions, hunting booty and cedars from Lebanon—dragged along for construction purposes—are enumerated alongside the number of slain enemies and the size of walls of conquered cities covered with their skins. In such cases, charisma is acquired irrespective of its bearer’s position in the kin or household, indeed, of any rules. This dualism between charisma and everyday life is often found among the American Indians, for instance, among the Confederacy of the Iroquois, tribes in Africa, and elsewhere.

Wherever war and big game hunting do not occur, we do not find the charismatic chieftain or rather the “warlord,” as we want to call him, to avoid the usual confusion with the peacetime chieftain. If natural calamities—drought or epidemics—are frequent, a charismatic sorcerer may have an essentially similar power and become a “priestly ruler.”

The charisma of the warlord rises and falls with its efficacy and the demand for it; the warlord becomes a permanent figure when there is a chronic state of war. It is mainly a terminological question of whether kingship and the state are said to begin with the annexation and incorporation of foreign subjects into the community. For our purposes, using the term “state” in a much narrower way remains expedient. As a rule, the warlord phenomenon is not linked to tribal domination over another tribe and to the existence of individual slaves but only to a chronic state of war and a comprehensive military organization.

However, kingship frequently develops into a regular royal administration only when the military following controls the working or paying masses. But the subjection of foreign tribes is not a necessary intermediate step. The internal stratification resulting from the development of charismatic warriors into a ruling caste may have the same differentiating effect. At any rate, as soon as their domination has been established, the royal power and those with vested interests in it, the royal following, search for legitimacy, that is for the mark of the charismatically qualified ruler.”

Charisma, Medieval and Modern

A special issue of Religions 2012

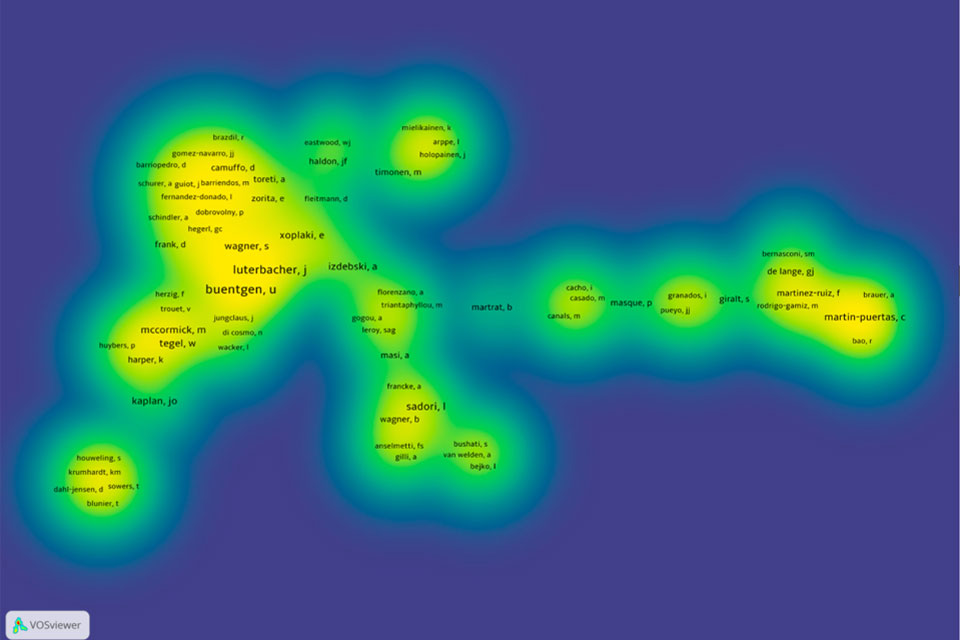

What Happens During Rapid Climate Changes? What can we learn from History?

Did climate changes in pre-Viking societies really matter? Did people adapt their agricultural strategies? Or were such changes just registered as temporarily “whacky weather” by the people of the past?

What was the Middle Ages known for? Why was it called the Middle Ages? What characterised the Medieval World?

Endless seals imprinted on wax! Countless pieces of parchment, neatly stacked. We tend to value these leftovers from the Middle Ages for their content. Matthew Collins sees aDNA.

The story of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is incresingly considered as a reflection of 4thcentury widespread draughts on the Eurasian Steppes, the wanderings of the Huns, and the forced migration of the Germans.

Europe in the Tenth Century is commonly allowed to stretch from 890 to 1030. Named since the 15th century as the “Century of Lead and Iron”, it was characterised by a significant shift from centre to the periphery, from France to Germany.

The famous royal seat at Avaldsnes on the West-coast of Norway is best known as the residence of Harold Fairhair, but excavations tell us about a splendid royal hall from the 13th century

Close to airport of Ostend in Belgium lies a proper hidden gem, the Walraversijde archaeological site – a medieval open-air museum

“I have planted a garden and dug a well. Now, come and be crowned with a wreath of roses and lilies…”(Martin Luther 1525)

Some may think that medieval gardens were all about cabbages, beans and medicinal herbs. But gardens also came to be intended for lush and frivolous play

What role did the Early Medieval climate changes play in the creation of the post-Roman world? Did people migrate because of the cooling weather?

The history behind the castle-building on hilltops in the medieval Mediterranean landscape – the incastellamento or incastellation – is nuanced