Early Byzantine textiles have survived almost exclusively in the hot and dry climate of Egypt, where the dead were buried in their clothing in furnished graves. Detailed studies of the collections in Germany continue to be published.

In the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century archaeologists working in Egypt discovered the many textiles, which had survived in the dry and hot climate of Egypt. But not only the linen in the Egyptian graves caught their interest. Significant collections of Byzantine textiles from Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages were created by enthusiasts and collectors working their way through the desert. Today, thousands of fragments and even whole pieces of clothing is kept in museums in Europe and the USA. The last ten to twenty years have seen an upsurge in the scientific studies of these invaluable pieces. Now publications lift the veil on the colours, the designs and the many uses of the sumptuous textiles, which came to characterise our understanding of the Byzantine Empire and the material culture, which came to dominate Eastern Mediterranean in this period. Below is a list of a few of the more recent publications presenting German Collections.

The RGZM – the Römisch- Germanisches Zentralmuseum – has an extensive collection of 220 early Byzantine textiles, which are currently being evaluated in terms of the production techniques involved, the function of the textiles and the chronology. Basis of the research is a textile-technological examination of each piece. The textile-technical data and the decorative scheme will often allow to determine the original appearance and thus the original look and use of objects, which only exist as highly fragmented pieces. The textiles in this collection have been divided into two functional groups: clothing and textiles serving as furnishing, equipment and functional textiles. Among the garments in the collection of RGZM are four full tunics and three full headcoverings. Textile technology studies have further identified 18 fragments of a front and/or back part of tunics, 15 tunic sleeves and three more head-coverings. Among Furnishing fabrics were identified 12 fragments of large-sized blankets that were often fitted to upholstery with ribbons. Six fragments derived from larger hangings, including a fragment, which must have belonged to curtain plus two other wall hangings. In the collection of RGZM are also two examples of functional textiles rarely encountered: A larger fragment of a hunting or fishing net from Karara and a thick covering or matting from the Egyptian city of Crocodilopolis. Here too, the manufacturing technique of the objects are closely related to their function. Both the clothing and the use of equipment and textiles show that the textile trade in the early Byzantium was highly developed and specialized. This collection has recently been published by Petra Linscheid.

Byzantine Textiles in Karlsruhe

The textile collection of BLM Karlsruhe contains 238 textiles from the early Byzantine period. Most stem from the collections amassed by the collections of Reinhard and Bock. These two well-known collectors of “Coptic” textiles sold parts of their collections of numerous major German and European museums and fragments and related pieces can be found in other collections. The fabrics are from early Byzantine graves in Egypt, more precise location information is not recorded. The fragments belong to the period between Late Antiquity and Early Islam (3 – 7th centuries). The remarkable thing about the collection in Karlsruhe, is the large number of those pieces that are of a relatively large size and with original edges. This is important, when trying to determine the former appearance and function of the pieces.

The collection holds two complete tunics and nine larger fragments. Especially important are thirteen fragments of early Byzantine silks that have been used as appliqued decoration on various garments. While some of these trimmings were probably cut from larger silk pieces, which were being recycled, other pieces of silk ornament have been woven to form. In the collection one may also find four full hairnets made in sprang technique. A total of fifteen larger fragments of curtains, draperies, rugs and upholstery fabrics illustrate the upscale home decor early Byzantine period. Two larger fragments with diffuse pattern can probably be identified as curtains. Other fragments demonstrate the use of decorating with loops made of bright bright linen threads.

Exceptional are two-colored embroidered stripes. Embroideries are rare in the early Byzantine period, as decorative pieces were usually worked as woven bands. Iconographic significance has a Clavus – a vertical band used on Roman tunics – with several New Testament representations, including Mary with the Christ child. This Clavus belongs technically and stylistically to a small but homogeneous group of tunics with biblical representations dated rather late in to the 7th-9th centuries.

This collection has not been published yet.

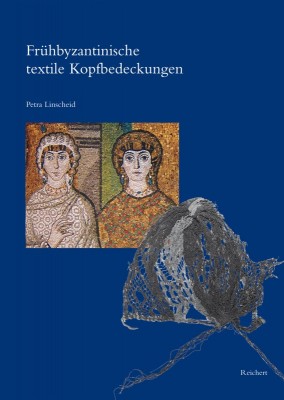

Hair-nets

An inkling of the abundance of material kept in these collections come from the study of hairnets, which was undertaken by Petra Linscheid as part of her PhD. This study was published in 2011. In connection with her doctorate she catalogued 600 original head-covers, preserved either whole or as fragments. Most of these pieces had until then not been published. The typology counted hairnets, scarves, hoods, caps and hats of diverse forms. Geographical and chronological mapping demonstrates that these types were used all over Byzantium in the whole period.

Most of these were worn by woman. However, different ypes were obviously worn by different social groups and served to differentiate people. Hoods were primarily worn by children and indifferent of their gender.

The catalogue, which accompanies the text, presents 610 different head-covers, of which 20 are presented in full colour.

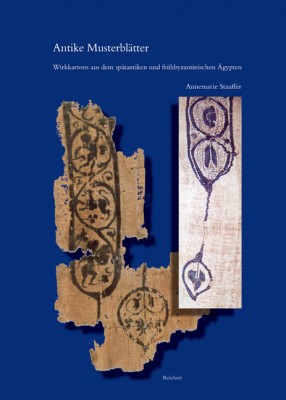

Papyrus Patterns

It is well-known that the Egyptian sand has not only preserved large collections of textiles and fragments thereof. Hoards of millions of papyri fragments have helped to make Byzantine Egypt one of the most well-known Mediterranean regions.

Part of these fragments have been studied by Annemarie Stauffer, who some years ago discovered papyri, which had obviously been used as patterns for weavers and textile workers in Egypt. This led to a systematic worldwide search through collections in order to discover more about this phenomena. She succeeded in finding more than a hundred such patterns. This allowed her to explore the ways in which such patterns were produced and how they were transformed into the medium of textiles. In a recent book (from 2008) she published a catalog of the papyri with corresponding items of preserved textiles, thus demonstrating the correspondence between the two media.

SOURCES:

Die frühbyzantinischen Textilien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums

Die frühbyzantinischen Textilien des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums

By Petra Linscheid with a foreword by Ina Vandenberghe

Schnell & Steiner 2016

ISBN: 978-3-7954-3037-5

Frühbyzantinische textile Kopfbedeckungen. Typologie, Verbreitung, Chronologie und soziologischer Kontext nach Originalfunden

Frühbyzantinische textile Kopfbedeckungen. Typologie, Verbreitung, Chronologie und soziologischer Kontext nach Originalfunden

By Petra Linscheid

Verlag Reichert 2011

ISBN: 9783895007217

Antike Musterblätter. Wirkkartons aus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten

Antike Musterblätter. Wirkkartons aus dem spätantiken und frühbyzantinischen Ägypten

By Annemarie Stauffer

Verlag Reichert 2008

ISBN: 9783895005848

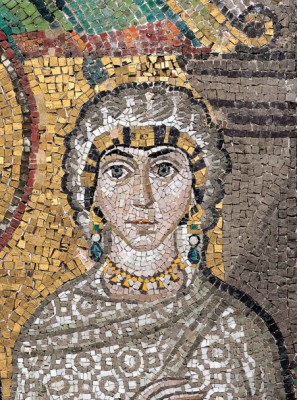

FEATURED PHOTO:

Early Byzantine curtain from Egypt © RGZM