When was Beowulf composed? In the 10th and 11th centuries as the Toronto School decided in a postmodern whiff? Around AD 700 as linguistic studies have proven? Or as an oral epos, around AD 550, and in Gotland as suggested in a new book?

Review:

Beowulfkvädet. Den nordiska bakgrunden.

By Bo Gräslund

Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi 149

ISBN: 9789187403279

In the 1980s a scandal broke out in Toronto. No longer a venerated poem of the Dark Ages, Beowulf was dated to the turn of the millennium and characterised as a very late Anglo-Saxon pastiche. Although metrical, linguistic, and palaeographic evidence was brought forward to staunch the postmodern erudition flowing from the medievalists – who had drunk from the poisoned chalice of Derrida, Baudelaire, and Kristeva – the standard bearers from Toronto nevertheless succeeded in banning the use of the text by historians and archaeologists. Under pain of shunning, students might no longer “use” the beautiful verses to illuminate the murky mead-hall.

In the 1980s a scandal broke out in Toronto. No longer a venerated poem of the Dark Ages, Beowulf was dated to the turn of the millennium and characterised as a very late Anglo-Saxon pastiche. Although metrical, linguistic, and palaeographic evidence was brought forward to staunch the postmodern erudition flowing from the medievalists – who had drunk from the poisoned chalice of Derrida, Baudelaire, and Kristeva – the standard bearers from Toronto nevertheless succeeded in banning the use of the text by historians and archaeologists. Under pain of shunning, students might no longer “use” the beautiful verses to illuminate the murky mead-hall.

Later, hard-core linguists were luckily able to turn the tide and reclaim the poem from this literary evisceration. Nevertheless, challenges have continued to mar the understanding of the epos and the cultural crucible, in which it was forged.

Finally, this summer, a magisterial and erudite analysis by the archaeologist, Bo Gräslund, was published in Sweden outlining the material world and a probable background for the text.

Let it be said initially. Bo Gräslund is the grand old man of Swedish Archaeology. He has worked at the National Museum in Stockholm as well as taught as a professor at the University in Uppsala. Apart from this, he has served as head of the Royal Academy of History and Antiquity, the Royal Gustavus Adolphus Academy, Royal Society of Arts and Sciences of Uppsala and several other august academies. To this should be added a very long list of publications. In his later years he has been occupied with outlining the events in the 6th century leading up to and following the climatic crisis AD 536 – 550. It is as part of this project, the study of Beowulf has been undertaken. Thus, Gräslund is not a perky young fellow with a fixed idea running wild on the fringes of the academic scene. He arrives at the scene with a solid ballast.

Further, the book is softly written, courteously and mildly. Yet, it delivers a decisive blow to the last 200 years debate and adds some well-argued propositions and hypotheses as to the what, where, when, and how of the Beowulf.

Then, what are his arguments?

First of all, we are met with a catalogue of the material culture of the late migration to early Vendel period. With its gold, rings, ring-swords, swine-helmets, and chain-mails, we are obviously transported way back in time, either prior to or around the period 536 to 50. Secondly, it is demonstrated that several of these particular artefacts are virtually unknown in an early Anglo-Saxon context. Not until the Viking Age, do we meet “rings” in the archaeological assemblies in Britain. Nevertheless, they are mentioned 44 times in the poem, and whenever they are further characterised, they are made of gold. How should an English poet c. 700 be acquainted with this particular cultural item – golden rings – which is never found in a British context, and which disappeared in Scandinavia in the late 6th century, Gräslund asks? As for ring-swords, it is important to note, that while three ring-swords have been found in England, most (77) have been found in France, Germany, and Scandinavia. And one of those – the one from Sutton Hoo – is probably Swedish, he writes. At the same time, he notes that the only chain mail ever found in an Anglo-Saxon archaeological context is from the same grave, making it a unique item in an English context from c. 400 – 1000. Finally, Gräslund draws attention to the fact that the descriptions of the cremations of Hnæfs and Beowulf have a sensual character, which makes it mind-boggling to imagine that a Christian poet c. 700 was able to describe these events in such details. Thus, the material culture of the poem does not fit at all with an Anglo-Saxon origin, Gräslund concludes.

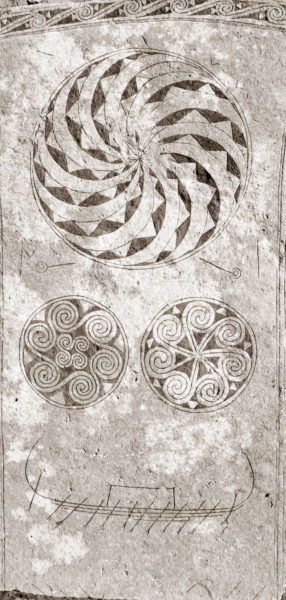

In the second part of the book, Gräslund discusses the ethnonyms in the poem and argues that the main group, to which Beowulf belongs – the Geats – in all likelihood came from Gotland. Seafaring islanders, known also as wederas, the latter epithet has been consistently translated as wind, weather, or storm. However, much more likely, writes Gräslund convincingly, the prefix in weder-geatas refers to Proto-Germanic wedrą, meaning ram – Old English weder, Old High German wetar, Old Norse veðr etc. It so happens, that rams were significant symbols of the people from Gotland, as witnessed in documents, sagas, and in the official seal.

Gräslund also touches upon the Christian varnish and concludes (as have others before him) that it seems to have been added as a gloss. In its core, the poem is heathen. This conclusion leads to Gräslund’s next hypothesis that the poem was composed as an oral epic in the mid-sixth century and probably in Gotland; but also that it would have circulated widely, for instance in a Swedish context at Uppsala.

We know Rædwald of East Anglia was married to a pagan princess who worked assiduously to make her husband relapse. We also know, that his presumed grave at Sutton Hoo held an assemblage of artefacts with a clear Swedish origin. Were these objects – the helmet, the chain-mail and the sword – bridal gifts of a Swedish princess? Did she bring a bard along in her entourage? After which the oral poem circulated untilit was written down by an Anglicising and Christianising scribe c. 700? We shall never know, but the hypothesis fits the facts as well as Ockham’s razor.

The third part of the book finally offers a close reading of the events in the text to see if they fit the historical facts of the events in 6th century Scandinavia, such as they may be gleaned from archaeological excavations and historical sources. Much here is believable, less, slightly hypothetical. The conclusion, however, is that the poem was composed in a volatile and dangerous situation in the mid-sixth century. In 536 – 41 a series of volcanic eruptions of frightening proportions caused a dust veil to wrap itself around huge parts of the world, forcing a dramatic climatic downturn. Average temperatures in northern and middle Scandinavia fell by 3 – 4 C˚ and the decade between 536 – 45 has been characterised as the coldest inside 2500 years. Other studies have shown that Norse poems like Hyndluljóð and Vafþrúðnismál in all likelihood were composed as comments to these events. Here and elsewhere (in Gylfaginning) we hear about the Fimbulwinter, a dark and frozen prelude to the events of Ragnarök causing hunger and untold suffering. Enter Grendel, a name, whose meaning hitherto has eluded scholars. Perhaps Grendel is derived from Old West Norse grenna (-grenda, grendr) meaning make thin, reduce, make gray. The name Grendel should accordingly mean the one who famish people. Grendel is the symbol of the great hunger. He is also a “guest” who under cover of the ethos of caring for strangers, eats out the people of Heorot, which by the way gets located on Stevns and not Lejre. Also, Gräslund notes, Grendel and his mother live in a black and swampy mist while the heavens cry (v.1374 – 1376). Possibly, this dismal place echoes the sodden and dark landscape, from which water is held back from evaporating by the cold weather and the lack of sunlight. In Gräslunds understanding, Grendel is a metaphor for the devastation caused by the sudden disruption of the weather in the mid 6th century.

It is a complicated argument, and readers deserve to be guided by Gräslund and not a foreshortened version in a review. Also, some of the points have been argued by other archaeologists and anthropologists over the years. So, please read the book for this vivid and enticing tour-de-force.

Accordingly, let the following suffice: Through the years, I have followed the painstaking effort of numerous scholars and linguists trying to come to grips with Beowulf and its cultural context. It is only fair to say that the last ten to twenty years have brought us much closer to a formal understanding of the text in its written Anglo-Saxon version. Gräslund’s tour de force, though, lifts us to another level. His study of “Beowulfkvädet” deserves to be translated into English as soon as possible. No time to waste. Perhaps the good people in Toronto may finally succumb and dress up in sacks and ashes. They ought to…

Karen Schousboe