Medieval Archaeology was late to achieve academic status in Spain. However, since 1985 a huge number of excavations have been carried out. Fascinating book presents an overview

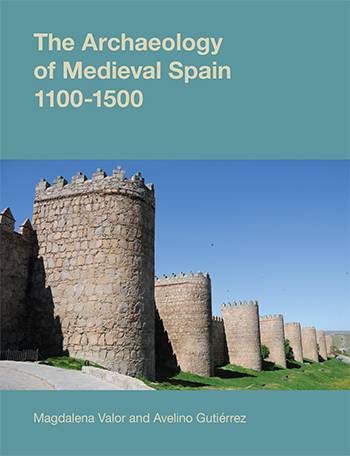

The Archaeology of Medieval Spain 1100 -1500

By Magdalena Valor and Avelino Gutiérrez

Equinox (2014) 2015

ISBN 978-1-78179-252-0

Equinox publishes a fine series of books presenting the archaeology of Medieval Europe in different countries and regions of Europe. First out, was the very fine book on Medieval London, 1100 -1600 from 2011. This was followed by a regional overview of the Archaeology of Medieval Spain 1100 – 1500. This is a very important second contribution to the series, which is poised to unfold in the following years (a recent addition is an The Archaeology of Prague and the Medieval Czech Lands, 1100-1600). For most of the 20th century Spanish Medieval History suffered from a inordinate preoccupation with written sources and the controversies fostered by the general political climate. Questions concerning the status of convivencia between Christians, Muslims and Jews – or the lack thereof – have thus played an important role as has the question of how to write the history of what is generally termed the “reconquista”, but might perhaps better be named the conquesta (a concept used in the present publication).

Equinox publishes a fine series of books presenting the archaeology of Medieval Europe in different countries and regions of Europe. First out, was the very fine book on Medieval London, 1100 -1600 from 2011. This was followed by a regional overview of the Archaeology of Medieval Spain 1100 – 1500. This is a very important second contribution to the series, which is poised to unfold in the following years (a recent addition is an The Archaeology of Prague and the Medieval Czech Lands, 1100-1600). For most of the 20th century Spanish Medieval History suffered from a inordinate preoccupation with written sources and the controversies fostered by the general political climate. Questions concerning the status of convivencia between Christians, Muslims and Jews – or the lack thereof – have thus played an important role as has the question of how to write the history of what is generally termed the “reconquista”, but might perhaps better be named the conquesta (a concept used in the present publication).

The question remains, however, exactly how people lived together in the Spanish Middle Ages: what did the medieval landscape look like? Were villages fortified or not? How did towns and cities function? What did castles and fortifications look like? What characterised the homes and domestic life of peasants, merchants and nobles? What material culture did people surround themselves with? How was trade conducted? What did ships look like? And finally, how was power – whether secular or religious – expressed in both life and death?

And not least: in which way differed the circumstances of life in the south – El Andalus – from that of the north – the Christian Kingdoms?

This book is packed with fascinating presentations of what archaeologists have found, especially during the last thirty years, and in what way the many finds shed light on these questions in a comparative cultural perspective. Each chapter is divided into two parts: one focusing on the material remains of El Andalus and the other on those of the Christian kingdoms.

Some might perhaps find the presentation of the topics a bit plodding. However, this would be most unfair. The authors and editors have succeeded in presenting both fine overviews and careful examples with a multitude of illustrations, maps and photos, thus securing the general reader a fine overview of the actual practicalities of living in medieval Spain.

One fine example is the presentation of the castle-palace of Olite in Narvarra (p. 194). This is a place historians might very well overlook as its impressive exterior is in fact no more than an empty shell. However, the “Palacio de los Reyes de Navarra de Olite” consisted of a complex of buildings with a very irregular ground plan, formed through successive centuries. It thus tells the story of how palatial living changed from the 11th century and up until the end of the Middle Ages. In its decorative schemes, it represented different types of stylistic inspiration derived from France and Castille as well as El Andalus and Catalonia –Majorca. First built around 1200, it was renovated already in 1265 – 9. In 1399 a whole new complex was added to the east of the castle offering a modern and very luxurious palace complete with “hanging gardens”, galleries and spatial living quarters for the kings and queens of Navarra. After 1420, this was followed up with a decorative scheme including Andalusi-style plasterwork, Moorish brick-layers from Tudela and Zaragosa, and coffered ceilings from Barcelona and Toulouse. Unfortunately, the conquest of Narvarre by Fernando of Aragón in 1512 marked the end of the royal use of the palace, and a process of deterioration began soon after. Today, the western (and oldest part) is used as a Paradores, while the eastern part is “still in reconstruction”. Unfortunately, nearly all of its rich décor has been lost forever. Reflecting upon life in 15th century Spain, it is nevertheless important to know about sites like this as well as (perhaps) visiting them; especially, if armed with the present guide. Such a combo would definitely enrich the understanding of both historians and literary scholars when tackling the rich written sources of Medieval Spain. Well written, it might even be a joy for any amateur trying to find their way into the material remains and archaeology of the Iberian Peninsula.

This is a most welcome publication, which should be a permanent fixture on any syllabus teaching the History or the literature of the Middle Ages in Spain. With more than 40 pages of literature plus an appendix with links to Spanish Medieval archaeology websites, the book really works as a splendid companion.

Karen Schousboe

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Magdalena Valor Piechotta is a Professor at the University of Seville

Avelino Gutiérrez is professor at the University of Orviedo

FEATURED PHOTO:

Castle or Palace at Olite, Navarre, Spain