Tikøb church in Denmark is unique. It is an imposing example of an early 12th-century brick church. Foremost, though, it features a series of striking portraits shaped in burnt clay. Three kings, a bishop – and an abbot, a monk and a horse on the north wall? Who might it be?

Valdemar the Great’s reign (1157-1182) is remarkable on many fronts – political, dynastic and cultural. Politically, he succeeded in establishing a royal dynasty with the official canonization of his father, Cnut Lavard, at the coronation party in Ringsted in 1170, where his son, Cnut VI, was made king. But Valdemar also made his mark in the subsequent military expansion in present-day northern Germany. Culturally, Denmark made a reorientation towards Western Europe, and especially France. This cultural inspiration involved a massive investment in the “new” Cistercians and the import of their advanced technological and artistic knowledge and craftsmanship.

One of the more prominent new cultural expressions was the royal and ecclesiastical support for the completely new and modern building technique which burnt bricks constituted. And which left a distinctive character in the Danish countryside, which we still encounter in the landscape.

From the lead plaque in Valdemar the Great’s grave in Ringsted Church, we know he and his surroundings also found the new construction method remarkable. On the plaque, the use of bricks in the rebuilding of Danevirke 1157 – 1170 is noticed in the longer text. “He was also the first to build a wall of burnt stone, which is generally called Danevirke, for the protection of the whole kingdom, and built a tower on Sprogø”, it says in the second inscription from 1202 on the lead plaque . And yes, the great Valdemar Wall was an impressive edifice.

However, the new building material, the brick, and the new architectural possibilities found their use in church buildings as well as in castles and fortifications. Today, several imposing church buildings are still impressive representatives of the fashionable new and modern building style. We might mention the churches of Ringsted, Roskilde, Århus and Sorø. But also smaller churches deserve to be mentioned, thus Tikøb near Esrum Kloster and Gumlösa in Sweden (inaugurated in 1191 in the presence of Absalon).

It has long been assumed that the new brick buildings were “invented” by the Cistercians in Klaarkamp in Friesland and Aduard in Groningen. But in fact, recent studies have shown that these churches and monasteries were built somewhat later than the earliest constructions in Denmark. The Danish Gothic brick churches are probably the first on the European map with almost simultaneous buildings in Saxony, Brandenburg and Bavaria. The Dutch and Flemish came later in 1210-1220. Unfortunately, sufficient scientific datings of bricks lack to be sure.

Where did the Cistercians get the inspiration? The answer is probably Lombard stone masters, who set their mark on Frederik Barbarossa and his noble companions and courtiers, who further drew their inspiration from the Crusades to Jerusalem about the biblical lands. Here, the Roman tradition of building with bricks had been preserved.

Likely, the idea of building with bricks was conceived in the international network of crusaders who travelled through Europe in the 12th century. Added to this were the ideas picked up by the Cistercians in the same milieu. Finally, in this period the growing European trade in wool was accompanied by the massive growth of cities and markets, not least the market in Champagne after 1180.

All this gave rise to a flourishing new elite preoccupied with the artistic expressions that can be summarized as Gothic, an artistic style generally dated to after 1150 and considered to have been inspired by Italian artists and builders under the influence of the Crusaders’ experiences in the Levant.

This new elite – led by a new and more absolute monarchy preoccupied with securing the hereditary kingdom and the idea of the dynasty – was woven into the Cistercians’ new reformed culture of piety, expressed in their quiet and simple aesthetics, for which the use of bricks was attractive.

Tikøb Church

A prominent example of the construction of such a cultural symbol is Tikøb Church. This church was built in the slipstream of the Cistercian formation at Esrum 1151 by Archbishop Eskil, a personal friend of Bernhard of Clairvaux. We know from a diploma issued by King Svend Grathe in 1148 that Eskil was able to donate the land at Villingerød and Esrum, which constituted the core of the new abbey, because his father, King (Erik Lam) had granted the permission. The land belonged to the so-called “Kongelev”, the property of the Crown, and not the king’s private possessions. Accordingly, permission to grant was to be given by the king, Svend Grathe, who in 1148 confirmed that Eskil was allowed to establish the foundation. Elsewhere we are told – in a letter from 1160 confirming Esrum Monastery’s possessions – that both Knud Magnussen and Valdemar the Great had gifted the Monastery

This context allows us to establish that the corner of North Zealand between the north coast, east coast and Esrum lake belonged to the royal domain. Likely, the region was so forested between AD 500-1000 that it fell to the Crown based on the motto: what belongs to no one, belongs to the king. The place-names indicate that clearings and settlements were primarily established in the region between 1000 and 1150.

Probably, the result was a clear division between the Abbey and the Crown. Where the Crown was located at Gurre with an early medieval castle from the Valdemarian period, the Abbey was located at Esrum, with the bishop at Søborg until 1161. The area’s only two parishes and churches: Asminderød and Tikøb were situated in between the Abbey and the royal castle. For a long time Tikøb was the largest parish in Denmark until 1876 (1887) also housing Hornbæk, Hellebæk, Egebæksvang and Mørdrup.

Tikøb – Tiwithcop – means “the purchase at the god’s forest” and is mentioned for the first time approx. 1170, where the Archbishop Absalon gifts Tømmerup forest, located in Tikøb parish (northeast of Villingerød). The same Tømmerup forest was a gift from his foster-brother, King Valdemar the Great. The village of Tikøb itself – later appears to belong partly to the Crown partly to the diocese of Roskilde. Finally, in 1487 King Hans granted the “church” with the rectory to the Abbey. At this point, we are told the rectory owed a pound of rye and a pound of barley in taxes together with a forest-fattened pig. Later (1660), the village housed five farms plus the rectory. The village of Tikøb itself was never impressive, but people sought church from afar. Therefore, we may conclude, the remarkable church still standing owes its grandeur to its royal owner.

The Church Building

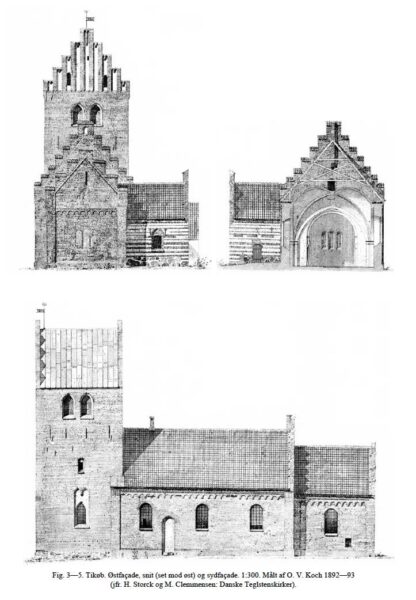

In 1957, archaeologists uncovered traces of a small wooden building under the present church. An earlier church, perhaps? However, in the second half of the 12th century (usually dated to ca. 1180), work began on the nave of the new church. On a foundation constructed of solid boulders, the brickwork rose distinctly and well-ordered, with rifled stones at all apertures, arches, friezes and cornices. At the south door, even moulded decorative stones were used. The brickwork was never plastered but kept blank.

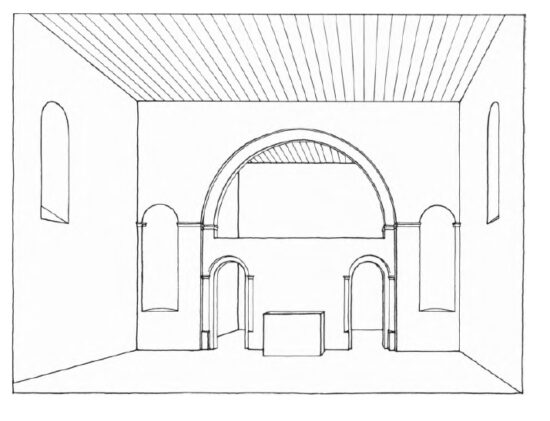

The light fell into the church through high-seated windows, three on each side. The doors themselves were high and narrow, providing entrance into the nave, which was carefully separated from the choir from the same date.

Thus, a solid chancel screen between the nave and the choir was erected and flanked by two narrow doors. In the middle stood an altar. On each side of the screen were brick niches fitted with side altars. The baptismal font – with paint residues – is now located at the former site of the screen but will originally have been placed in the western end. The baptismal font is a Romanesque stonemason’s work made of Hör sandstone from Scania by Alexander (as stated in the frieze). The baptismal font is considered unique in its artistic expression and believed to date from the same time as the church.

Today the church is vaulted (from the 14th century) and with a tower from the 15th century and a sacristy from 1517.

Portraits?

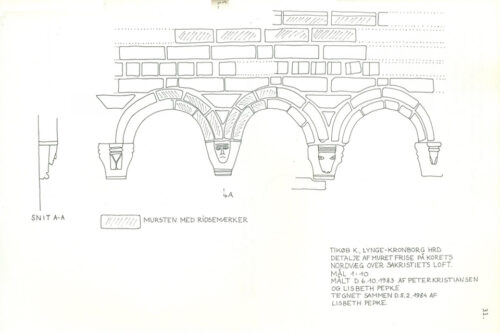

Particular attention must be paid to a series of portraits bearing the relief arches on the outside walls of the nave. Shaped in wet clay and then fired, five individual sculptures have adorned both the southern and northern walls of the nave.

The portraits show us three crowned heads as well as a person with a mitre, now partially destroyed. At the northern wall is what appears to be another cleanshaven head. Behind the sacristy added in 1517, yet another two portraits are hidden. Drawn up in 1984, they have never been published. However according to the drawing, they show a monk and what appears to be a horse. The primary individual traits of the three royal heads consist of facial hairs and headgear – crowns, diadems and mitres – with a rather unidentifiable headcover on the portrait on the north wall.

We have no definite clue as to who are portrayed here. Hence, any identification must be considered tentative.

Nevertheless, the three crowned portraits placed next to each other are suggestive. Might they refer to the period between 1146-1157, when three crowned kings ruled Denmark: Svend Grathe, Knud Magnussen and Valdemar the Great? Or as we know them: Svend, Knud and Valdemar (Sweyn, Cnut and Valdemar). Waging a more or less continuous civil war from 1146-1157, the three cousins occasionally joined forces. Thus, in 1147 the three kings jointly went on a crusade to Venden. However, the portraits can hardly originate from this fragile period of peace. Esrum Abbey was first founded in 1151; likely, the architect and builders used the Abbey’s brickworks and skilled workforce.

Another – and more likely – option is the three kings met at the invitation of Archbishop Eskil (or the bishop in Roskilde, Asser) to celebrate their reconciliation in Tikøb at the run-up to the so-called blood feast, a peace banquet in Roskilde in August 1157, which ended in the coldblooded murder of Cnut and the final victory of Valdemar at the heath of Grathe in the autumn . Might the portraits be a reminder of the peacekeaping efforts in the summer of 1157?

The identification here – which of course is nothing but very tentative – is then as follows: First Valdemar (Vladimir), who at the settlement in the spring of 1157 became King of Jutland, Knud Magnussen to whom the islands fell, and Svend Grathe who was given Skåne, Halland and Blekinge to rule. These portraits are then followed by the Archbishop Eskil (?) or another bishop; finally, the unidentifiable person with no facial hair on the northern side might perhaps be identified with the abbot of Esrum?

However, the three portraits might also be identified as the three wise kings, Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar. In which case, however, the following “bishop” represents a curious choice. Or the figureheads may point to the three righteous kings, Saul, David and Solomon, renowned in the high middle ages for their inspirational qualities as to what “kings” were meant to be. Or the portraits may have been intended to send multiple connotations to all three groups of kings.

Incidentally, the artist’s role models seem to be taken from coins. From another portrait of Valdemar the Great – from the tympanum in Schleswig Cathedral and coins – we know that this king wore a pointed moustache and a fully rounded beard. Hence the tentative identification here with the relatively youthful portrait to the west.

SOURCES:

The very beginning of brick architecture north of the Alps: the case of the Low Countries in the question of the Cistercian origin

By: Alexander Lehouck

From: L’industrie cistercienne (XIIe – XXIe siècle). Actes de colloque de Clairvaux-Troyes-Fontenay, 1er-5 septembre 2015, Paris: Somogy éditions d’art (pp.41-56)

Ed. By: A. Baudin, P. Benoit, J. Rouillard and B. Rouzeau

Somogy éditions d’art 019

Tikøb Kirke. Lynge-Kronborg Herred.

Danmarks Kirker

Nationalmuseet 1967

Esrum Klosters brevbog : Oversættelse bd. 1 – 2

Udgivet i oversættelse med indledning og noter af Bent Christensen … et al.

Selskabet til Historiske Kildeskrifters Oversættelse af Museum Tusculanum 2002