Some may think that medieval gardens were all about cabbages, beans and medicinal herbs. But gardens also came to be intended for lush and frivolous play

When calendars in the Later Middle Ages began to change the illuminations for May of peasants digging, ploughing, pruning and chopping their way through shrubbery and undergrowth, with those of people planting flowers, the pleasure garden had long been an important part of the houses and homes of the elite. Now, however, it also became the joy of burghers and perhaps even peasants. The development of this idea that a garden should be not just useful, but also delightful took many centuries.

When did Gardens become kitchen-yards?

Walking through Pompeii, it is evident that the Romans adored gardens and filled them with a profusion of sprinkling fountains, abundant exotic fruit trees and furniture intended to provide comfortable seating for a leisurely time in the cool shadows. In the aftermath of Late Antiquity people apparently still prized their gardens. Thus, Gregory of Tours tells us about the garden of St. Martius, who was abbot of Clermont in Auvergne. St. Martius had his monks grow a “garden filled with a lot of various vegetables and fruit-trees; it was at the same time beautiful to look at and pleasing in its fertility. In the shade of its trees, whose leaves murmured gently at the breath of wind, the blessed man usually sat.” [1] Later, we hear how a thief entered the garden at night and “gathered some vegetables, onions, garlics, and fruits”. Unfortunately, that thief could not find his way out of the garden with his illicit victuals, but that is another story. What we should not here is the obvious idea of Gregory that a garden was not just an intensively farmed plot of land. It was also a pleasure. Such was also the case with the opulent garden, which the French king Charibert I (c. 517 – 567) according to Venantius Fortunatus granted to Ultrogotha. The garden plot was next to the Church of St. Vincent, which served as her husband, Childebert’s, mausoleum. Later she was buried there next to him, and it is likely this garden was intended more as a Christian Cemetery than a pleasure garden as such. This garden was said to offer shade from vines and apple trees, granting a foretaste of Paradise. Obviously, the reference to the vine-stock is also a symbolic reference to the church [2]. Elsewhere Venantius wrote of his poor garden close, which did not yield roses but only violets, which he could bring to Radegund.

However, when the Benedictine monk, Walafrid Strabo (c. 808 – 849), wrote his Hortulus, a treatise on gardening, he no longer waxed lyrically about the garden as a token of Elysium. Now the garden had evidently turned into a place where you were sure to get hard calluses all over your grubby hands.

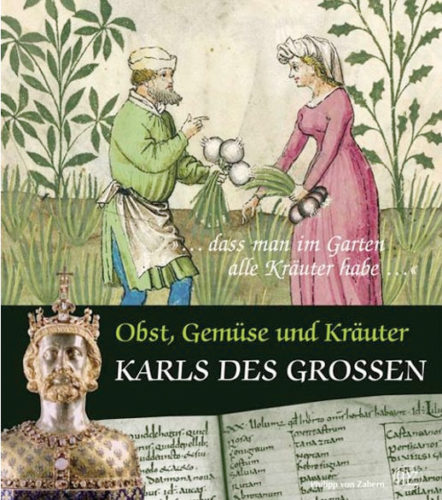

“We Wish to Find all Sorts of Herbs in Gardens”

Kitchen gardens are of course known from numerous more prosaic sources, like laws, capitularies, polyptychs and charters, as well as archaeological excavations. From these, we know that kitchen gardens were ubiquitous in the medieval agrarian landscape from Iceland in the north to the Mediterranean coastal societies in the south. Plants might differ, though, catering for different traditions and palates.

Several Carolingian sources supply us with a detailed overview of what was at least expected to be found in a proper kitchen garden in the Frankish empire of Charlemagne. In his Capitulare de villis [3] nearly a hundred different sorts of herbs, vegetables, nuts, and fruits. We even get a sense of the way in which a garden could be so much more than just a fenced and manured piece of land. Listed is for instance also the so-called sempervivum tectorum L – the common houseleek – which we hear that every gardener (hortulanus) must have on the roof of his house. Of course, this is a reference to the ancient superstition that this particular herb would protect against lightning strikes. Another fine source is the plan of the Abbey of St. Galen.

Probably, these idealised kitchen-gardens left the reality far behind. However, we do know that people could be both inventive and entrepreneurial. Early on, plants were thus imported; also into the countryside. First by monks and wandering clerics, who helped to spread them into the garden of the local vicar; from where it likely passed on to the peasants. Spinach is such a vegetable. At first introduced to the Iberian peninsula by the Muslims, it was later brought north of the Pyrenees by the Cathars, who may have imported it via their network of wandering” perfects”.

Arabic and Norman Gardens

Although we find evidence of ornate and elite gardens in Carolingian sources [4], useful gardens continued to dominate the European literature and art until the Normans “discovered” the Arab gardens in Southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century. Arabic inventions were not just the introduction of new trees like the pistachio three, or the citrus fruit trees, which came to spread their flowery scent and sweet and sour tastes of their nuts and fruits on the tables of the new rulers. Another lovely introduction was the mulberry tree, which did no just serve as a home for the larvae of the mulberry silkworm, but which also yielded sweet berries To this must also be added the marvellous new vegetables like the carob, pistachio, eggplant, spinach. However, the cultivation of these fruits and vegetables rested heavily on the ingenious use of water, which had led the Arabs to adopt the old Persian and Middle Eastern tradition for irrigation and the mastering of canals, ditches and water-fountains.

The numerous palatial buildings and gardens in Palermo preserved from the time when the Normans ruled Sicily witness to this. Thus, the garden of Maredolce-La Favara mainly consisted of an artificial lake, which not only held numerous species of fish but also served as a pleasure lake, maredolce, literally meaning sweet-water-lake. In the centre of this lake was the “sollazo”, the “solace” of Roger II. Here, he went together with his court to spend time leisurely paddling on the lake while imbibing the sweet fruits of his predecessors. Other significant remnants are the palaces of Cuba and Zisa, notable for their elaborate fountains and the engineering, which lay behind the control of flowing water in all its disguises. [5]

No wonder, some of the earliest references to ornamental gardens may be found in the circle of crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries, who experienced this garden culture, either first hand in the Middle East or by extension, in Sicily and Andalusia. Thus, recent scholarship [6] has uncovered the close connection between several French and British elite centres from the late 13th to early 14th centuries and the gardens in Palermo. Such was the case for two northern gloriettes at Leeds Castle in Kent and Hesdin in Pas-de-Calais. Both were commissioned by King Edward I and Count Robert II of Artois, respectively, after they had passed through Palermo in 1270 – 72. Other such gloriettes have been identified at the castle in Lillebonne and the town of Arbois. The earliest mention of an early gloriette on English soil is found in a survey from 1260 of the castle at Corfe. This particular gloriette consisted of a lavishly decorated royal palace, which was erected inside the inner bailey, and enclosed by an extensive hall-range and kitchen block. On the northern side, the king and his retinue could take a stroll in the garden and gaze at the magnificent keep.

Such gloriettes were chambers or suites inside the main compound of high-status residences and were perhaps not in themselves indicative of being part of medieval gardens. Nevertheless, the inspiration may have come from a poem, the anonymous Prise d’Orange (c. 1190), in which a sumptuous palace was described with its marble columns, silver windows, pine and carob trees, herbs as well as frescoes depicting lions and birds roaming in a garden. Although sketchy, we get a sense of the palace inserted into and nearly transformed into an enclosed garden.

About Growth, Plants and Artful Gardens

“Nothing refreshes the sight so much as fine short grass. One must clear the space destined for a pleasure garden of all roots, and this can hardly be achieved unless the roots are dug out, the surface levelled as much as possible, and boiling water is poured over the surface, so that the remaining roots and seed which lie in the ground are destroyed and cannot germinate… the ground must then be covered with turves cut from good grassland, and beaten down with wooden mallets, and stamped down well with the feet until they are hardly to be seen. The little by little the grass pushes through like fine hair and covers the surface like a fine cloth”

Quoted from Christopher Thacker: The History of Gardens, London 1979, p. 84. For the Latin text see, De Vegetabilibus Libri VII, ed. C. Jessen, Berlin 1867, p. 636 – 637.

BnF: Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms-5064 réserve

Sometime in the mid-13th century, the Dominican friar, Albertus Magnus (1200 -1280) wrote a book, called “De Vegetabilibus et Plantis”, in which he compiled a vast amount of earlier herbals. However, Albertus magnus also included a famous description of a leisure garden complete with green lawns. Although his recommendations were intended for a garden in a monastery, they were soon adopted outside after Piero de’ Crescenzi, a Bolognese lawyer, who wrote another manual, the Ruralia Commoda (c. 1304 – 1309). Dedicated to the King of Naples, Charles the II, a French translation was carried out in 1373. Other garden-authors were Matthaeus Silvaticus and Gualtherus.

It is also during this period we encounter gardens as meaningful contexts for significant literary achievements like the “Roman de la Rose”, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and the German epic, King Laurin, which is known to belong to the group of texts called the “Rosengarten group”. Although these poems used the motive strictly allegorically, they do testify to the widespread recognition of the Rose Garden as a beautiful and amorous spot.

At the same time, we see a preponderance of illuminations showing delightful gardens cropping up in manuscripts. Demonstrating what a properly enclosed medieval garden would look like behind the hedges, fences or walls they showcase flowery meadows, orchard trees, flower-beds with topiary plants, as well as benches, fountains, trellises and arbours. Many of these illuminations show the Virgin Mary teaching the Christ-child to read.

Late Medieval Gardens

In the 15th century, gentle gardening had turned from an elite preoccupation to a bourgeois pastime. Early evidence is the chapter on horticulture, which an elderly French gentleman wrote to his young wife at the end of the 14th century when he handed her the responsibility for his household. Through his admonitions we get an excellent introduction to their garden in Paris – or perhaps the plot, she gardened on the outskirts of Paris. Thus we learn which month she should plant fava beans, peas, kale and cabbages, spinach, chard, leeks, squash, lettuce, fennel, and orache. Of herbs, he mentions parsley, marjoram, violets, savoury, sorrel, basil, borage, and rosemary. Added to this is advice on how to graft and care for fruit trees – vines, cherries, plums. Finally, she is told to plant peonies, serpentines, lily bulbs, rosebushes and currant bushes after the Feast of the Nativity of our Lady – the 8th of September. Was this a garden intended to be plainly fruitful? Probably! But it also seems to have included flowers for which no particular use can be found except the ubiquitous medicinal. Roses might be utilised for rosewater or to scent clothes. But peonies seem to have had no special use apart from medicinal (which is not indicated).

Finally, though, it is fascinating to read how our Parisian recounts advice he has received from some of his noble acquaintances. He tells us that “he have heard it said to Monseigneur de Berry that the cherries are much larger in Auvergne than in France (Île-de-France), because they graft their cherry-trees there”. Also, we learn that a Monseigneur de Rivière helped to introduce to Paris seeds of a particular sort of lettuce from Avignon. It appears, that already at this point, the noble and the wealthy were personally involved in gardening, sharing, tips, tricks and seeds. [7]

No wonder, one of the very first secular books to be printed was the work by Piero de’ Crescenzi in 1471 in Augsburg; with more than 57 editions from the next century, this witnessed to the widespread popularity of gardening in Early Modern Europe.

NOTES:

[1] Gregory of Tours: Life of the Fathers.

Tr. And ed. By Edward James. Liverpool University Press 1991, p. 92

[2] Venantius Fortunatus, Carmina VI.2, lines 21-26 and VI.6, lines 3 – 16. Se also: The Humblest Sparrow: The Poetry of Venatius Fortunatus. By Michael John Roberts. University of Michigan Press, 2009, p 92.

[3] Introduction to the list of herbs, Charlemagne expected to find in the gardens of his peasants as stipulated in his Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii: “We Wish to Find all Sorts of Herbs in Gardens”.

[4] In the Capitulare de Villis, § 40, we read “That every steward, on each of our estates, shall always have swans, peacocks, pheasants, ducks, pigeons, partridges and turtle doves, for the sake of ornament”. Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii

[5] ”Paradies der Erde” – wasserinszenierungen in den Normannerpalästen Siziliens.

By Hans-Ruldolf Meier. In: Wasser in der mittelalterlichen Kultur / Water in Medieval Culture: Gebrauch – Wahrnehmung – Symbolik / Uses, Perceptions, and Symbolism. Ed by Gerlinde Huber-Rebenich, Christian Rohr, Michael Stolz

Walter de Gruyter 2017, p. 601 – 613

[6] Aristocratic Power and the “Natural” Landscape: The Garden Park at Hesdin, ca. 1291–1302.

By Sharon Farmer.

In: Speculum (2013), Volume 88, Number 3, pp. 644 – 680

La Zisa/Gloriette: Cultural Interaction and the Architecture of Repose in Medieval Sicily, France and Britain.

By Sharon Farmer

In: Journal of the British Archaeological Association (2013), pp.

[7] The Good Wife’s Guide. Le Ménagier de Paris. A Medieval Household Book.

Tr. by Gina L. greco and Christine M. Rose. Cornell University Press 2019, pp. 209 – 214

FEATURED PHOTO:

Castelnaud-la-Chapelle, overlooking the Dordogne River in Périgord © Wikipedia/Boutry

READ MORE:

READ ALSO: