Abelard and Heloise has left us some of the most heart-wringing and evocative love letters ever written. In the 19th century a cult developed among lovelorn youngsters at Père Lachaise

But among the thousands and thousands of tombs in Père la Chaise, there is one that no man, no woman, no youth of either sex, ever passes by without stopping to examine. Every visitor has a sort of indistinct idea of the history of its dead and comprehends that homage is due there, but not one in twenty thousand clearly remembers the story of that tomb and its romantic occupants. This is the grave of Abelard and Heloise — a grave which has been more revered, more widely known, more written and sung about and wept over, for seven hundred years, than any other in Christendom save only that of the Saviour. All visitors linger pensively about it; all young people capture and carry away keepsakes and mementoes of it; all Parisian youths and maidens who are disappointed in love come there to bail out when they are full of tears; yea, many stricken lovers make pilgrimages to this shrine from distant provinces to weep and wail and “grit” their teeth over their heavy sorrows, and to purchase the sympathies of the chastened spirits of that tomb with offerings of immortelles and budding flowers. Go when you will, you find somebody snuffling over that tomb. Go when you will, you find it furnished with those bouquets and immortelles. Go when you will, you find a gravel-train from Marseilles arriving to supply the deficiencies caused by memento-cabbaging vandals whose affections have miscarried.[1]

The Pere Lachaise Cemetery

Nowadays, most people visit the cemetery of Pére Lachaise in Paris to see the grave of Tignous, the satirical cartoonist, who was murdered in the onslaught of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015; or the graves of Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, and – perhaps – Chopin, leaving gifts of coloured pencils, beer and vomit, lipstick-kisses or flowers.

Curiously enough, though, no one seems anymore to leave flowers at the tomb of Abelard and Heloise, even though this used to be the famous meeting place for unrequited lovers in the 19th century. Perhaps – in this time and day – there no longer exists such a thing as hopeless love, but only the regrets of divorcees.

Originally a rural property belonging to a medieval merchant – Régnault de Vendôme – who built a small “folly” there, the vineyards were later taken over by the Jesuits, who built a country house there. During the reign of Louis XIV, his personal confessor, François de la Chaise, lived there. After the dissolution of the Jesuit order in 1764, the city bought the property and in 1802 it was converted into a cemetery.

Now, forgotten, it was in fact Abelard and Heloise, who were the first incumbents of the new park.

Abelard and Heloise

Among medievalists, the story of Abelard (1079 – 1142) and Heloise (c. 1090 – 1164) is well-known. Abelard was the eldest son of a noble Breton family from Pallet: in his youth he was encouraged to study and around 1100 he arrived in Paris where he set up diverse schools teaching philosophy and logic. In around 1115 he got the coveted position as Master of Notre Dame and canon of Sens. Full of himself at this point he gathered numerous pupils around him, among whom was Heloise, the niece of another canon, Fulbert. Arguably, she was at least as learned as him and the to ended up having an affair which led to her pregnancy. She was sent packing to his family in Brittany, while Abelard continued teaching. To appease her uncle, Abelard proposed a secret marriage, but Fulbert disclosed the marriage publicly, which led Abelard to pack Heloise off to a convent in Argenteuill. Whether this drastic act was taken to protect her or his own career is disputed. Nonetheless, it led to Fulbert hiring a gang to attack Abelard and castrate him. This led Abelard to become a monk, while forcing Heloise to take wovs as a nun.

During the next ten years, Abelard and Heloise were apparently not in touch. Abelard pursued his career as a scholar, now as a theologian; ultimately, this led to charges against him as a heretic as well as a number of other controversies with the religious communities he lived in. There is no doubt he was famed not only as a brilliant philosopher, but also a person who did not suffer fools. At some point he lived as a hermit at a place he called the Paraclete. When the nuns at Argenteuil – to whom Heloise belonged – were expelled, he offered them his former heritage as a refuge. Here Heloise built the foundation for what later became a fabled abbey.

It is sometime during this period, that Abelard wrote his autobiography, the Historia Calamitatum, which he send to Heloise. This prompted her to write back telling the story from her point of view, thus initiating one of the most famous lover’s correspondences from the Middle Ages. While the first four letters were deeply personal, the last three must be regarded more as letter treatises outlining the daily life and rule, which should govern the life at the Paraclete. As such, they should be read as an introduction to the moral treatises, which Abelard published in the late 1130s. This famously led to a second process against him this time spearheaded by Bernard of Clairvaux, who accused him of heresy. Saved by Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, Abelard spent his last years there as a revered and wise scholar. He spent his final months at the priory of St. Marcel near Chalon-sur-Saône before he died there in April 1142.

Soon after Peter the Venerable wrote a comforting and very sweet letter to Heloise telling her about the last days of Abelard as well as promising that “God now enfolds him in His embrace in place of you, as another you, and He keeps himthere for you until the coming of the Lord, and the voice or the archangel, and the trumpet blast that signals the descent of God from heaven, when through grace he will be restored yo you yet again.” [2]

Later Peter took it upon himself to have the remains secretly exhumed from the grave at St. Marcel, after which he personally brought them to the Paraclete, were they were laid to rest beneath a table, assuring the reader that Abelard had been absolved of “all his sins”. Obviously, the intention was to secure that the old spectre of heresy should not rise once more and lead to the desecration of the grave of Abelard. Later Heloise was laid to rest in the same spot.

Series of Tombs

During the next centuries, the convent and later Abbey at the Paraclete gained increasingly importance and several times, the bones of the illustrious couple were re-interred in steadily more elaborate settings. The last of these tombs were erected in 1779, only to be destroyed during the Revolution. After the dissolution, the place was sold and the bones of the couple were once more transferred, now to the local church of Nogent-sur-Seine. Finally, in 1800, a painter, Alexandre-Marie Lenoir(1761 –1839) acquired the remains in order to have them exhibited at the new Musée des monument français. At this event the bones and sculls were meticulously inspected and measured.

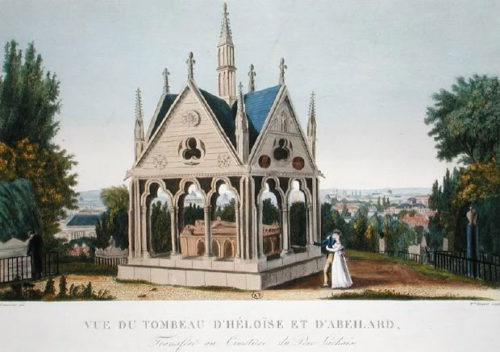

Later that year Lenoir also acquired fragments of the original effigy, which had been erected in the church in St. Marcel. These disparate elements plus the two salvaged inscriptions from the Paraclete constituted the nucleus of the first tomb, built by Lenoir to hold the remains of Abelard and Heloise. This was on view at the Jardin Élysée by 1802. Central were the preserved effigy of Abelard and a reconstructed one of Heloise made from a headless female sculpture from the 14th century, which was fitted with a new head in order to lie next to her lover and husband.

Later, on top of or around the tomb, a special sepulchral chapel was designed by Lenoir and built from bits and pieces of medieval spoliae, acquired from now defunct religious institutions from the Middle Ages such as the Carmelite church at Metz, the Saint-Germain-des-Prés, etc. Another feature, planned but not executed, were glazed windows, which were intended to be fitted into the arcades. This, however, was never, carried out.

These disparate elements were then artfully spliced together into which is arguably one of the finest neo-gothic edifices ever created in the early 19th century. It was also the centre of a grand idea, whereby the Jardin Èlysée was designed to be a commemorative locus of the now secularised national heroes. Here, their story became a timeless reminder of love – whether hopeless or fulfilled – as a common romantic denominator bridging untold generations of young people, in search of the “forever and ever”.

Today, the many “original” elements, which Lenoir used to construct the edifice, have been replaced or altered in connection with later restorations; also the chapel is standing somewhat derelict, devoid of attention. Apart form the odd medievalist, no one seems to care any longer; and it is definitely a long time since forlorn lovers have used it as a mailbox.

Today, it seems, Père Lachaise has become something quite different, namely an overcrowded lapidarium catering to the need of being buried among the famous French “heroes” – the intellectuals, the artists, and the composers.

If Abelard and Heloise have any role to play is this, it is perhaps more as philosophers and scholars, and less as lovers!

[1] From: Innocents Abroad. By Mark Twain. Bliss & Co. 1869. P. 140

[2] Quoted from: Abelard and Heloise. The Letters and Other Writings. Translated, with introduction and notes, by William Levitan. Hackett Publishing Company, inc. 2007, p. 271.

FEATURED PHOTO:

Abelard and Heloise at the Pere Lachaise cemetery. Source: Wikipedia

SOURCE:

A Tomb for Abelard and Heloise.

By Mary B. Shepard. In Romance Studies (2007), Vol. 25, 1, pp. 29 – 42.

READ MORE: